The third TARTLE exhibition – 1918–1945 / Kaunas–Vilnius

In its third exhibition, the Lithuanian Art Centre Tartle presents an exceptional part of its collection, offering a broad look at artistic life in Kaunas and Vilnius during the interwar period and the Second World War. The interwar period attracts much attention from cultural historians and art historians, and it also continues to attract popular attention. The public interest and the willingness to develop a deeper appreciation of the cultural and historical contexts of those years help to foster a sense of pride in the state, as well as enlightening the viewer. However, most exhibitions on this theme do not present Lithuanian art and Polish art from the first half of the 20th century together. They often fail to include artistic reflections on the situation in Vilnius, the former capital of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania: this limits the opportunities to compare the situations in Kaunas and Vilnius, both of which were important artistic centres, and to discuss differences in trends in artistic expression and cultural life.

This exhibition presents well-established figures in the visual arts of Lithuania and Poland, such as Adomas Galdikas, Antanas Gudaitis, Jerzy Hoppen, Bronisław Jamontt, Juozas Mikėnas, Tymon Niesiołowski, Petras Rimša, Antanas Samuolis, Ludomir Sleńdziński, Stasys Ušinskas, Justinas Vienožinskis and Antanas Žmuidzinavičius. Paintings, sculptures, prints, drawings, photographs and publications from the Tartle collection are displayed, providing a multifaceted presentation of the cultural and social contexts of those extremely complex years.

The ground floor of the gallery is devoted to portrayals of the two cities, the phenomena of the capital and the former capital, immortalised in works by artists and photographers. Whereas the image of Kaunas appears to have been shaped by Lithuanian artists who were anchored in national feeling and the spirit of modernity, the image of Vilnius that was developed by local artists emphasised tradition and romantic inspiration from the past. A common historical narrative is evoked, along with an interpretation of it in Lithuanian and Polish public life and art. The Vilnius question, which still occasionally flares up, is not swept under the carpet, either: it is represented by both serious and ironic images from propaganda art.

The downstairs rooms of the gallery present artistic life in Kaunas and Vilnius during the period from 1918 to 1945. Much attention is devoted to Kaunas Art School and Stephen Báthory University’s Faculty of Art, two institutions that shaped the main artistic trends of the time. The works on display illustrate the differences between these two traditions: Kaunas was open to artistic experimentation; Vilnius expressed moderation and a tendency towards Neo-Classicism. Works of art that have become classics of the period are included, as are other less characteristic examples, which are intended to stimulate a broader discussion on the diversity of the art of the period.

The exhibition not only takes a new look at the rather familiar situation of artistic life in Kaunas as the interim capital of the Republic of Lithuania. It also offers a closer look at artistic life in Vilnius, as a regional centre in the Second Polish Republic.

Works have been lent to the exhibition by the Lithuanian National Museum of Art, National Museum of Lithuania and the Ars Via auction house.

Dovilė Barcytė, Ieva Burbaitė – Art historians and exhibition curators

Photo credits: Andrius Stepankevičius, Antanas Lukšėnas

Video author: Edvardas Volginas

The digitization of the exhibition is funded by Lithuanian Council for Culture

![]()

read more

Image of the city

The image of the city (Kaunas or Vilnius) has been chosen as the leading motif in this room. In other words, the phenomena of the current and the former capital are emphasised, as they are immortalised in works by artists and photographers. First, we encounter the iconography of Vilnius, promoted and elaborated by Vilnius-based artists who were fascinated with the mood of Romanticism, steeped in tradition, and looking to the past. The image of Vilnius, perceived as the seat of high culture, was woven from treasures of the tangible and intangible cultural heritage, historical and sacral architecture and interiors, legends, and Catholic feasts, with their longstanding traditions.

View of the exposition

This retrospective look at the heritage and the traditions of the city is characteristic of prints, especially in the series of engravings called ‘Old Vilnius’ by Jerzy Hoppen, a student and later a professor at Stephen Báthory University. The room includes Hoppen’s work showing the façade of the Church of St Peter and Paul, one of the most prominent examples of Baroque in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, with a 17th-century procession of noblemen in front of it. An engraving by Jan Gintowt-Dziewałtowski, showing a detail of the interior with stuccowork by Italian sculptors, is displayed next to it. Hoppen’s students Walenty Romanowicz and Leon Kosmulski portray Vilnius within the same iconographic programme.

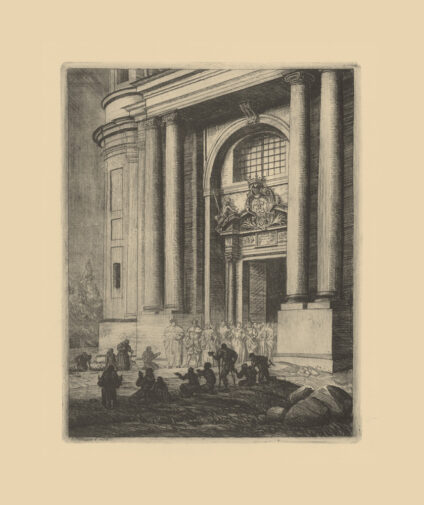

Jerzy Hoppen (1891–1969)

The Church of St Peter and St Paul, 1927, etching on paper, 26 × 21

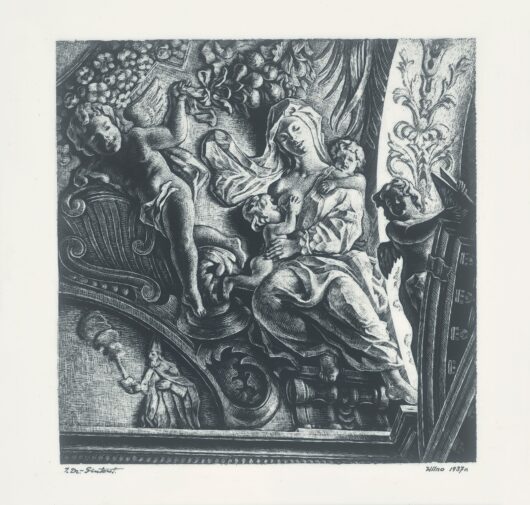

Jan Gintowt-Dziewałtowski (1904–1980)

Mother (Compassion), 1937, engraving on glass covered with ink, 18,4 × 18,2

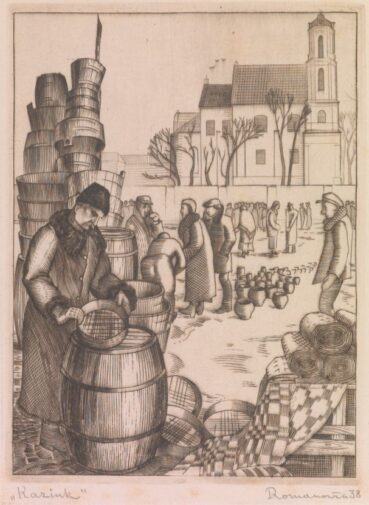

Walenty Romanowicz (1911–1945)

Kaziukas Fair, 1938, woodcut on paper, 20 × 15

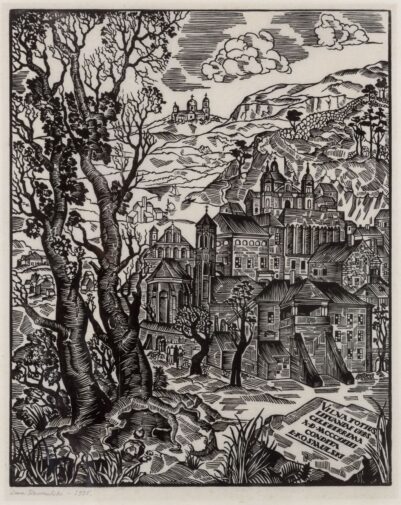

Leon Kosmulski(1904–1952)

Vilnius, 1935, woodcut on paper, 37 × 29,5

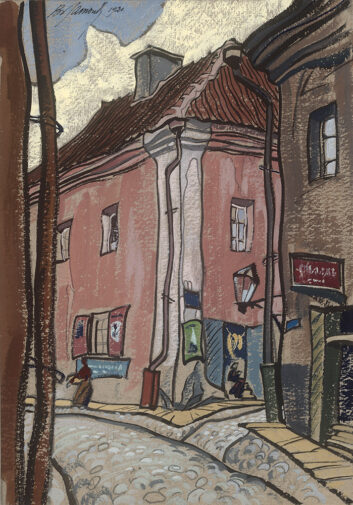

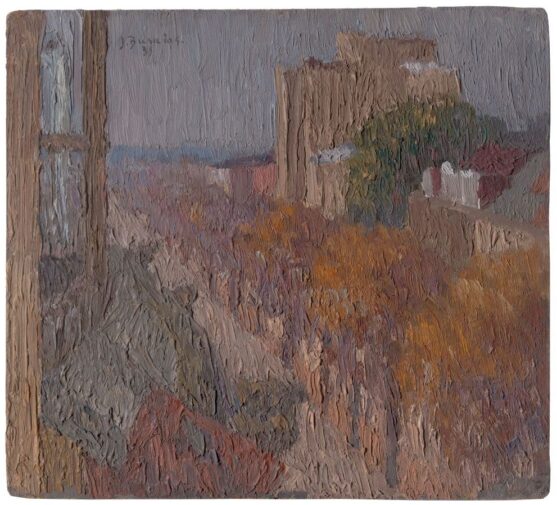

The paintings by Bronisław Jamontt and Jan Gintowt-Dziewałtowski stand out with their personal views of the city. Jamontt painted Gaon Street in the Art Nouveau style, which is rather unexpected for Vilnius iconography. Jan Gintowt-Dziewałtowski chose an unusual vantage point from which to portray a visual symbol of the city, the monument on the Hill of Three Crosses, which was designed during the First World War by the architect Antanas Vivulskis.

Bronisław Jamontt (1886–1957)

A side street in Vilnius, 1921, tempera and gouache on paper, 25 × 18

Jan Gintowt-Dziewałtowski (1904–1980)

The Hill of Three Crosses, 1937, oil on canvas and cardboard, 60,5 × 39

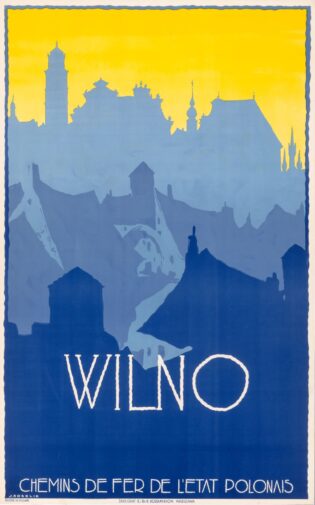

It is not known whether Stefan Norblin ever visited Vilnius: he was commissioned by the Polish Ministry of Transport and the State Railways to design a poster showing the city as a place worth visiting on a tourist map of Poland. The poster shows the stylised silhouettes of iconic churches in Vilnius, and a corner of the old Jewish quarter, in the Art Deco style.

Stefan Norblin (1892–1952)

Vilnius, 1928–1930, colored lithograph on paper, 99,8 × 62,3

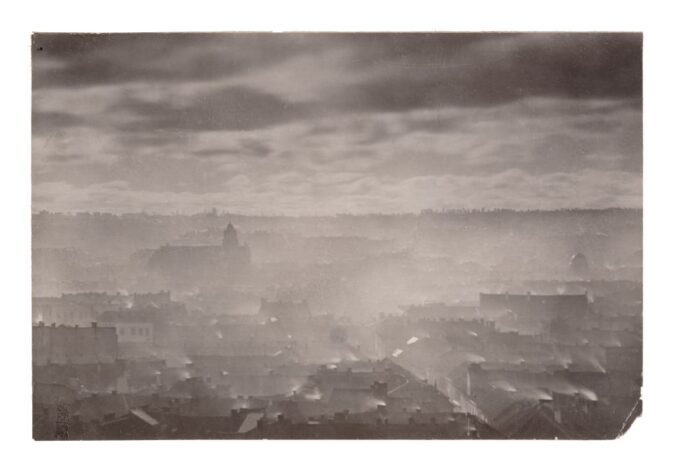

The photographs by Jan Bułhak should be mentioned, in order to place the narrative of the image of Vilnius in a broader context. He lived in Vilnius from 1912, and shaped a lyrical and dignified image of the Baroque city in the minds of citizens of the independent Republic of Lithuania, seeing it with romantic eyes in an Impressionist manner. Bułhak spearheaded the development and teaching of photographic art in interwar Vilnius. He headed the Department of Art Photography at Stephen Báthory University from 1919. He was an exponent of Pictorialism. (Originating in England and gaining an international following, this photographic style emphasised the pictorial and painterly aspects of photography.) In political and aesthetic terms, his work stood out from the photography that was practised in Kaunas and Vilnius at the time.

Jan Bułhak (1876–1950)

View of Vilnius Old Town, 1918, photograph, 10,5 × 16

Jan Bułhak (1876–1950)

Vilnius. The Gates of Dawn, 1923–1930, photograph, 11,7 × 16,3

Jan Bułhak (1876–1950)

Vilnius. Kaziukas Fair, 1920s–1930s, photograph, 11,5 × 16,4

In contrast to Vilnius, which was shrouded in a mythical aura, the iconography of Kaunas was shaped by Lithuanian artists who expressed national feeling and modernity. The image of the interim capital, and of modern Lithuania, had to be built up from scratch, based on two main ideas. On one hand, the national character of the new capital was exemplified by the use of folk symbols from the past (such as rural crafts). A poster designed by Mstislav Dobuzhinsky to represent Lithuania in 1937–1939 at international exhibitions in Paris and New York is a good example.

View of the exposition

On the other hand, Kaunas was represented as a new, modern and growing city. The interim capital came second after Vilnius in terms of its historical, architectural and sacral heritage, and its continuity of cultural traditions. But by the end of the 1920s, Kaunas was undergoing intense modernisation, and turning into a European metropolis. The Vytautas the Great (Aleksotas) Bridge was constructed in 1930, and can be seen in paintings by Vladas Eidukevičius and Jonas Buračas. Laisvės Avenue was given a major overhaul and resurfaced with tarmac in 1931 and 1932.

Vladas Eidukevičius (1891–1941)

Kaunas from Aleksotas Hill, 1930, oil on canvas, 79 × 100

Jonas Buračas (1898–1977)

Kaunas Old Town from Aleksotas, 1942, oil on carboard 45 × 28

Jonas Buračas (1898–1977)

Laisvės Avenue, 1931, oil on carboard, 25,7 × 28,3

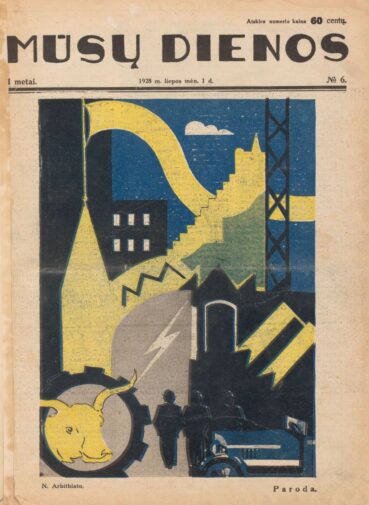

The link between national and modern Kaunas is clear in the medal that Adomas Galdikas designed for the Lithuanian Agriculture and Industry Exhibition. A Modernist vision of Kaunas is also evoked by a reproduction of Arbit Blatas’ work Exhibition. We see a radiophone tower, and stylishly dressed people beside a luxury car, while Taurus, the symbol of Kaunas, is integrated into an attribute of the industrial world, a cogwheel, which also features in Galdikas’ medal.

Adomas Galdikas (1893–1969)

The medal of the Agricultural and Industrial Exhibition in Lithuania, 1930

Silver-plated cooper, Ø – 5,9

Arbit Blatas (1908–1999)

Exhibition. Mūsų dienos (1928, No. 6)

Heritage of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

Lithuanians were united in their goal to reclaim their lost historic capital, and in a shared history that was closely linked to heroes from different periods. Grand Duke Vytautas, probably the main hero in the national pantheon, took the place of honour. His coronation, which did not take place, and the 500th anniversary of his death, were marked solemnly in 1930 both in Lithuania and in the Polish-ruled Vilnius region. Kaunas and Vilnius both had their own Vytautas the Great committees to arrange suitable events to mark the jubilee.

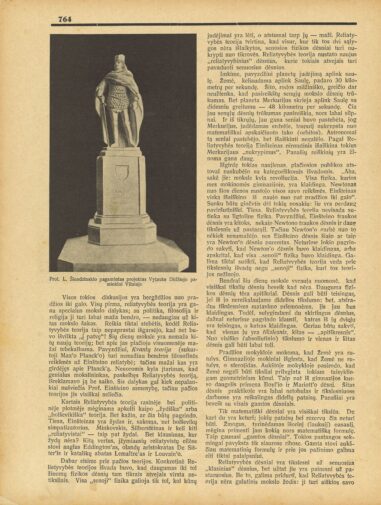

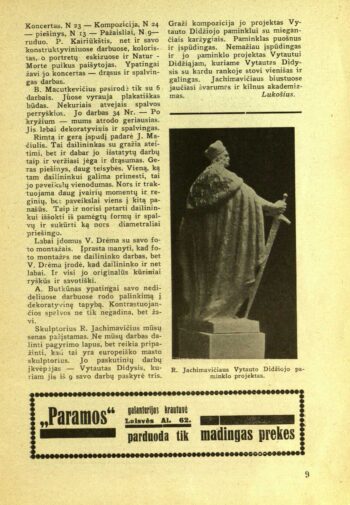

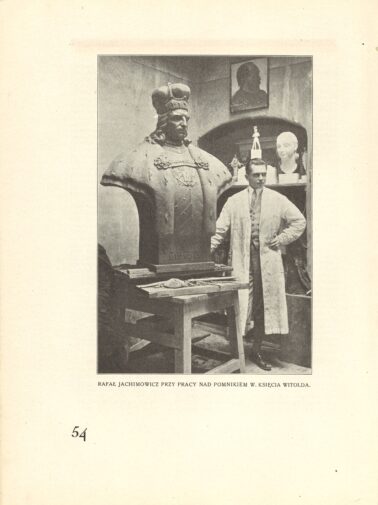

Both capitals devised plans to erect a monument to the grand duke. The original proposal for Vilnius was to be in the tower of the Upper Castle. Later, the decision was made to put up a monument in front of the ruins in the courtyard of the Upper Castle. Although the plan was never carried out, the conflict it sparked between two participants in the competition, Ludomir Sleńdziński, a professor at Stephen Báthory University, and the Vilnius-based Lithuanian sculptor Rapolas Jakimavičius, had serious repercussions. Sleńdziński accused Jakimavičius of plagiarism in his model for the monument. A court ruled in favour of Jakimavičius in 1932. The Polish and Lithuanian press followed the story closely, and the case assumed a political nature. Jakimavičius was one of the few Lithuanian artists living in Vilnius at the time. A bust of the grand duke based on a different design by him was unveiled in the Church of St Nicholas in Vilnius in the same jubilee year.

Ludomir Slendziński (1889–1980)

Model of the monument to Vytautas the Great, 1931, Naujoji Romuva (1931, No. 32)

Rapolas Jakimavičius (1893–1961)

Model of the monument to Vytautas the Great, 1930, 7 meno dienos (1932, No. 76)

The sculptor Rapolas Jakimavičius next to the monument of Vytautas the Great created for the Church of St Nicholas in Vilnius, 1930, Alma Mater Vilnensis (1930, No. 9)

When the independent Republic of Lithuania marked the 500th anniversary of the death of Vytautas in 1930, a portrait of the grand duke by Petras Rimša went round all the districts of Lithuania, carried in a procession by important public figures. Monuments and other commemorative symbols of varying artistic quality were made all over the country. One of the most famous, by Vincas Grybas, was unveiled in 1931 at Aukštoji Panemunė in Kaunas (it was taken down in 1951, and re-erected on Laisves Avenue in 1990). A plaster bust of the grand duke, a model for the monument, is displayed.

In addition to these grand monuments, some rather practical objects were designed to immortalise the memory of Vytautas. Busts, medallions, medals and portraits were intended to decorate the interiors of state institutions and private houses. The exhibition features the obverse of a medal set in marble. It is a variation on the famous portrait by Rimša that toured Lithuania. Alongside these professionally made patriotic compositions, there were quite a few amateur attempts to create commemorative pieces. A portrait of Grand Duke Vytautas carved in wood by an unknown artist is one. These artefacts were meant to foster a feeling of patriotic pride in the country’s history. Kaunas often invoked the story of Grand Duke Vytautas when it sought to surround itself with a similar mythological aura to that of Vilnius.

View of the exposition

Vincas Grybas (1890–1941)

Vytautas the Great, 1920s–1930s, plaster, h – 60

Petras Rimša (1881–1961)

The medal on a marble base in commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the death of Vytautas the Great, 1930

Bronze, marble, Ø – 10

Unknown artist

Vytautas the Great, 1930, wood, 49 × 29

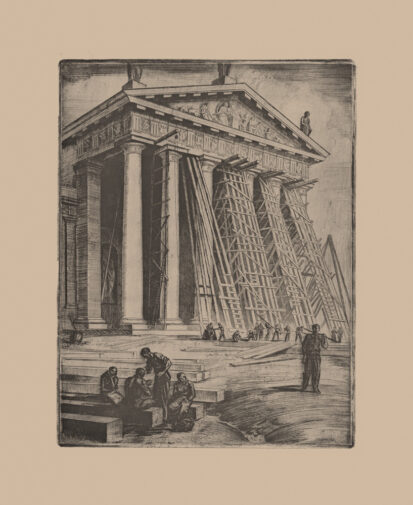

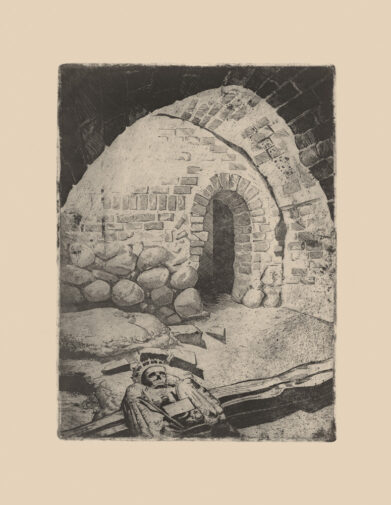

The discovery of the Royal Crypt in the vaults of the Cathedral in September 1931 after the spring flood was a powerfully symbolic event. During the restoration and reinforcement work on the structure and foundations of the Cathedral, and the digging in the hope of finding the tomb of Grand Duke Vytautas, a crypt was found containing the remains of King Alexander Jagiellon and two wives of Sigismund Augustus (Elizabeth of Austria and Barbora Radvilaitė). The Royal Crypt and its relics were not open to the public, so works of art and photographs that recorded this unusual discovery were exceptionally important. Images of the finds were published in the press, and prints of them were reproduced. Travelling exhibitions were held in Vilnius and Warsaw. The event was important both to Poland and Lithuania. The discovery reinforced the image of Vilnius as a historic Polish city, and at the same time it rekindled the hope among both nations that finding the remains of Grand Duke Vytautas was not an impossible aim.

Jerzy Hoppen (1891–1969)

Repairs to Vilnius Cathedral, 1933, etching on paper, 43 × 34

Jerzy Hoppen (1891–1969)

The remains of Barbara Radziwiłł in the Cathedral, 1933, etching on paper 41 × 31

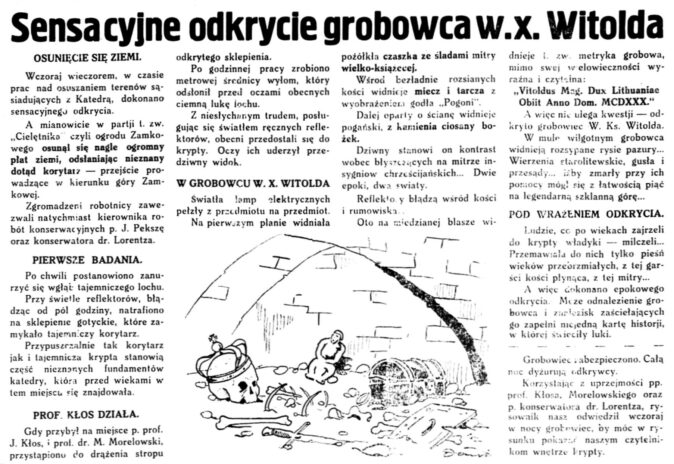

A different, ironic approach to the cult of Vytautas and the search for his relics, and by the same token, of the pagan culture of the Lithuanian dukes, was reflected in an illustrated article in Dziennik Wileński on 1 April 1932 announcing the ‘discovery’ of the site of Vytautas’ burial.

Dziennik Wileński (1932, No. 74)

View of the exposition

Signs of propaganda in art

Reclaiming Vilnius was a unifying goal. It brought together all sections of society and different political forces.

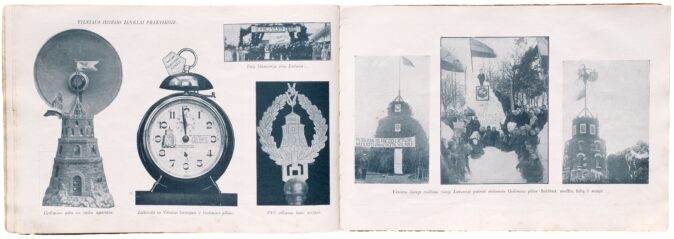

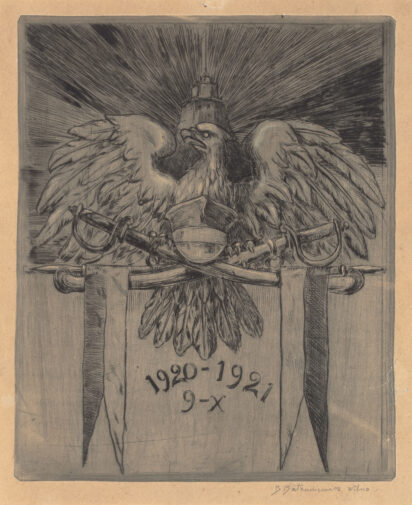

After the 1920 occupation of Vilnius by General Lucjan Żeligowski, Lithuania mounted an extensive, almost 20-year-long, propaganda campaign to reclaim the capital. Artists joined in enthusiastically. Public life and the press proliferated with arguments that Vilnius was an occupied Lithuanian city. Demographic concerns faded compared to the damage done to the identity of the country by losing Vilnius as its historic capital. Poland, which is usually represented by an eagle, its heraldic symbol, was cast negatively in contexts related to the Vilnius question.

A poster designed by Petras Rimša in 1920 calling on every citizen to struggle against the Poles is an example of Lithuanian propaganda art. The same composition appeared on postcards and medals, and in small graphic prints during the interwar years. Rimša created the prototype for this composition in 1912: it was a variation on his controversial sculpture The Battle, which he broke up himself on the third day of the 6th Exhibition of Lithuanian Art in Vilnius. Showing a stallion standing on an eagle, it caused an uproar among visitors and in the Polish press. Both the original and the 1920s composition used the same image and conveyed the same message about the Polish-Lithuanian conflict, which in the later case was deepened by the tension over the loss of Vilnius.

View of the exposition

Petras Rimša (1881–1961)

Poster ‘Citizen! To the struggle against the Poles!’, 1920, printing ink on paper, 107,5 × 76,5

There were no diplomatic relations between Lithuania and Poland in the 1930s, so travelling to Vilnius and its region was no simple matter for Lithuanians. Lithuanian passports stated that they were valid for travel to all countries except Poland. By contrast, Lithuanians acquired Vilnius passports issued through a section of the Vilnius Liberation Union, the Vilnius Iron Fund, not for the sake of freedom of movement, but inspired by patriotic feeling. All citizens of the Republic of Lithuania, ‘big and small, rich or penniless’, were encouraged to acquire such a booklet of donations. After paying a certain amount to the Vilnius Liberation Union, the holder of one of these passports received a sticker showing the donation. The money collected in this way was put towards reclaiming Vilnius.

Donations booklet ‘Vilnius Passport’ of Vilnius Iron Fund, 1930s

Donations booklet ‘The Great Vilnius Passport’ of Vilnius Iron Fund, 1930s

Writers also bemoaned the painful loss of the capital. The best-known example is the 1922 poem by Petras Vaičiūnas Hey, World, which was a second national anthem for 17 years. The poem was put to music by Antanas Vanagaitis, and sung at public and private events.

Promotional Film about Kaunas Before the World War II, 1930s.

Cameraman: Kazimieras Lukšys, Jonas Kazimieras Milius, Stasys Vainalavičius

Lithuanian Central State Archives

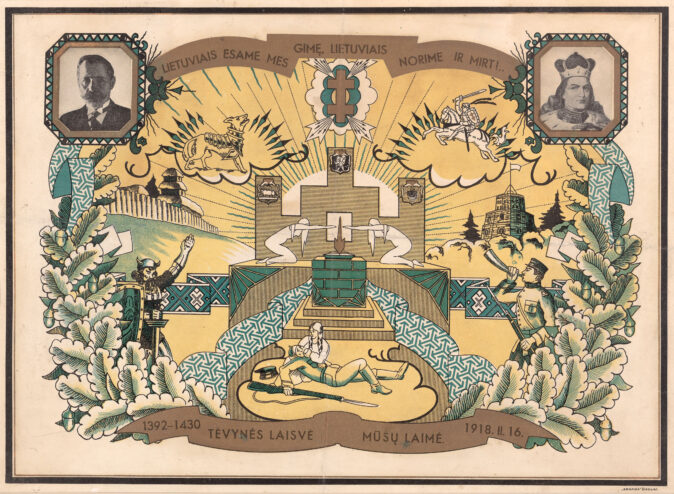

Vilnius, the historical capital, and Klaipėda, the country’s seaport, critical to its economy, were both perceived as integral parts of the state. Vincas Dilka’s poster We were born Lithuanians… expresses this feeling. It shows the Columns of Gediminas decorated with the coats of arms of three cities, Kaunas, Vilnius and Klaipėda. The portraits of Antanas Smetona and Vytautas the Great stress the historical continuity of the state.

Vincas Dilka (1912–1997)

Poster ‘We were born Lithuanians…’, 1937, mixed media on paper, 32 × 42

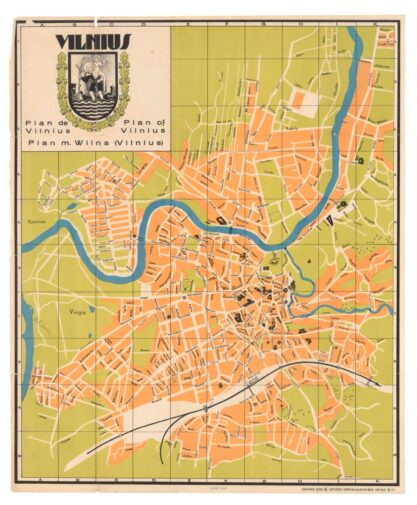

In the hope of giving Vilnius a more Lithuanian character, streets in the city were renamed in Lithuanian, even if it meant having to coin new names. The Vilnius Liberation Union, and especially Mykolas Biržiška, one of its founders, did notable work to that end. A guide to Vilnius by Jonas Vytautas Narbutas, which was published in Kaunas, was withdrawn from circulation in 1938 because of its Polish street names. The following year, a new revised and expanded edition came off the press, with a Lithuanian-Polish and Polish-Lithuanian list of street names compiled by Biržiška. It gave Lithuanian translations next to the Polish names, or proposed entirely new names. Thus, Sokola Street was rendered as Sakalų, while it suggested naming Safjaniki as Sapnininkų Street, and Gazowa Street as Stuokos Gucevičiaus. Biržiška removed names that offended patriotic feelings, and also introduced some names that were of symbolic importance to Lithuanian culture. For example, Piłsudskio Street was renamed Algirdo, Tylioji Street was renamed Vinco Kudirkos, and Fabriko Street was renamed Birutės. The display includes a 1938 map of Vilnius designed by Balys Macutkevičius featuring Lithuanian street names.

Balys Macutkevičius (1905–1964)

Vilnius city plan with Lithuanian street names from ‘A Guide to Vilnius’ by J. V. Narbutas, Kaunas, 1938

View of the exposition

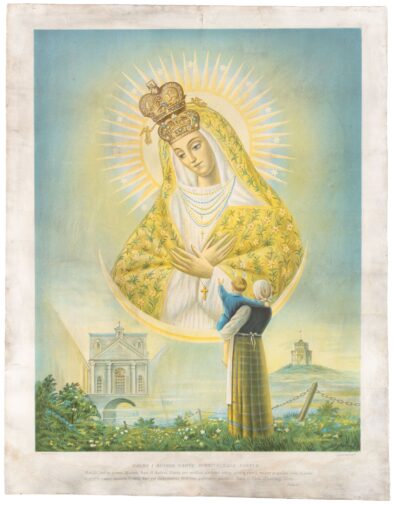

Vilnius was usually represented in Lithuanian art and in the press by easily recognisable symbols. Images of Gediminas’ Castle and its surroundings, the Cathedral, and the Gates of Dawn and the painting of the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Gates of Dawn, were the most widespread. These symbols appealed to patriotic feeling, and they summed up the essence of Vilnius for Lithuanians as the historic capital of Lithuania, and at the same time as a deeply Catholic city, so that the Lord’s help could be invoked in reclaiming it. For instance, a poster by Vaclovas Kosčiuška, A prayer to the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Gate of Dawn, uses all of these symbols: Gediminas’ Castle, the Gates of Dawn, and the painting of the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Gates of Dawn, with a Lithuanian woman with a child in her hands appealing for the Virgin’s intercession. A picture in Naujoji Romuva of a bookshop window (the shop in Kaunas was owned by the St Casimir Society) shows a collage in the Art Deco style, with a similar composition with the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Gates of Dawn. It combines religious and political aspects, and the Virgin Mary is invoked to ‘bless the hopes and aspirations of our nation’. These are clearly references to the Vilnius question.

Vaclovas Kosciuška (1911–1984)

Poster ‘A prayer to the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Gate of Dawn’, 1920s

Color printing on paper, 50,4 × 39

Gediminas’ Castle and the Gates of Dawn are very important symbols with a strong emotional charge. It is no surprise that these motifs are frequently used in works of art and the lyrics of songs. They circulated in art and in the official press, among the intelligentsia, and also among the less educated.

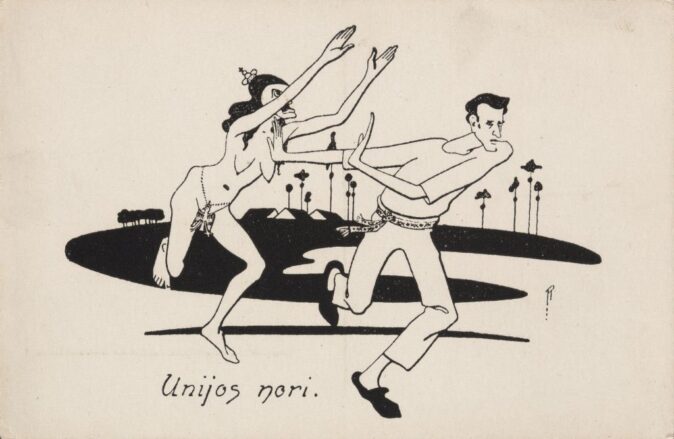

But they were not reserved exclusively for serious and solemn contexts. The surroundings of Gediminas Hill and the Cathedral often appear in caricatures published in periodicals, while Petras Rimša opted for a radically bolder treatment of these images. In his medal Union desired, Poland is personified as a grotesque female figure devouring Vilnius citizens against the background of the Cathedral. In Gediminas’ Dream from 1920, Vilnius is occupied by a pig wearing the cap of a Polish uniform. The artist’s work was undiplomatic: his inflammatory images offended the American-Polish community when the works were exhibited in the USA.

Publication Free Lithuania Without Vilnius by the Union for the Liberation of Vilnius, editor Vincas Uždavinys, Kaunas, 1935

Petras Rimša (1881–1961)

Medal ‘Union desired’, 1925, bronze Ø – 26

Petras Rimša (1881–1961)

Union desired, 1920s–1930s, postcard, 9 × 14

Petras Rimša (1881–1961)

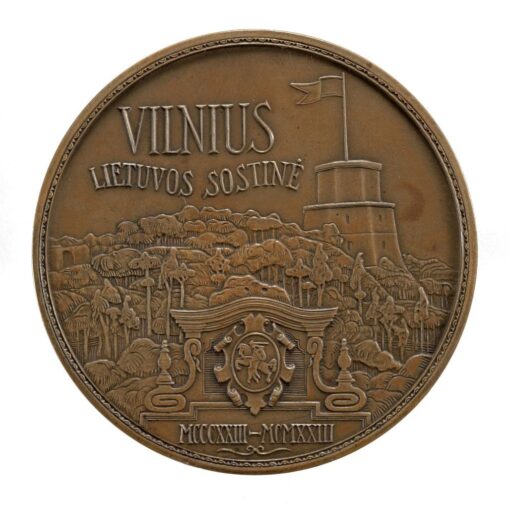

Medal ‘Vilnius 1323/1920’, 1927, bronze, Ø – 9,7

Petras Rimša (1881–1961)

The medal of the 600th anniversary of Vilnius, 1923, bronze, Ø – 7,5

Petras Rimša (1881–1961)

Medal ‘Let us liberate Vilnius’, 1926, bronze, Ø – 10

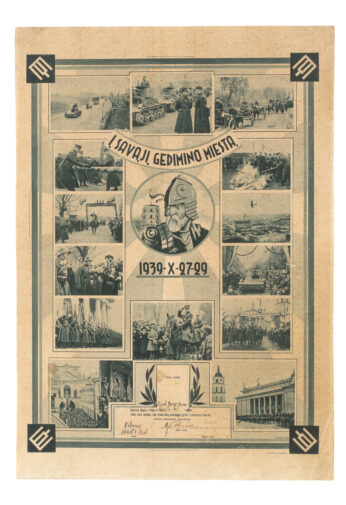

When Lithuania reclaimed its historic capital, artists started devising compositions that combined Lithuanian images with Gediminas Hill, the Cathedral and the Gates of Dawn. The entry of the Lithuanian army into the city attracted special attention. Pictures of this moment show crowds of people welcoming the Lithuanian units. All kinds of symbolic signs were published to mark the event. A certificate was designed for those who marched into Vilnius by Vladas Norkus, showing Gediminas and his castle, together with pictures of the Lithuanian army entering the city. The moment the military units arrived was called ‘a march’, a word chosen to make historical parallels with Lithuania in Medieval times.

Vladas Norkus (1909–1976)

To our own town of Gediminas 1939-X-27-29, 1939, printing ink on paper, 46 × 31,5

The bas-relief Mother of the Gates of Dawn, protect our Lithuania by Rapolas Jakimavičius shows a view of Cathedral Square full of people welcoming the Lithuanian army entering Vilnius in 1939. The Virgin Mary appears in a composition of architecture representing different Lithuanian towns. It was a symbolic way of putting this iconic image of Vilnius into a Lithuanian context.

Rapolas Jakimavičius (1893–1961)

Mother of the Gates of Dawn, protect our Lithuania, 1943, copper alloy, 56 × 36,5

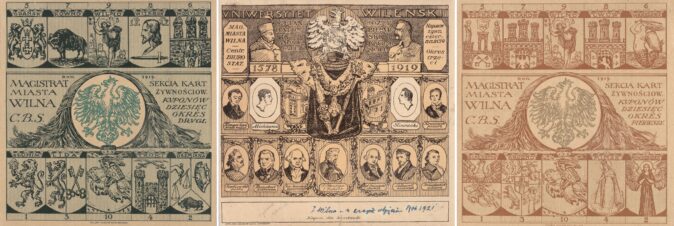

Official Polish compositions representing Vilnius used the same symbols of the city, but the designs featured the Polish eagle next to Gediminas’ Castle or the Gates of Dawn, instead of the Columns of Gediminas.

Polish interwar art associated Vilnius with several narratives. It was depicted as the centre of the voivodeship, as a city that was central to the Polish identity. Food stamps designed by Ferdynand Ruszczyc show the Vilnius coat arms of next to the Polish eagle and the coats of arms of other Polish cities. The history of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania is perceived as an integral part of Polish culture. Stamps with heraldic symbols also showed images of notable historic figures who contributed to the flowering of Polish culture, the city, and the whole country.

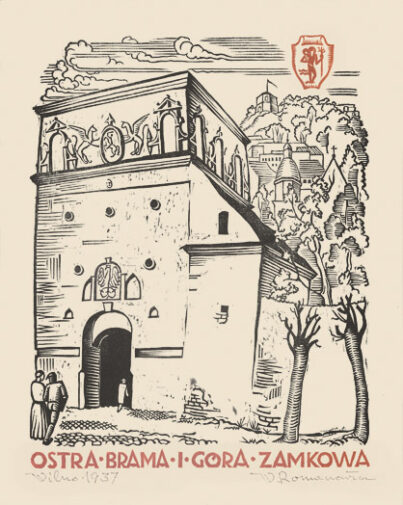

Walenty Romanowicz (1911–1945)

The Gates of Dawn and Tower Hill, 1935, woodcut on paper, 20,2× 16

Ferdynand Ruszczyc (1870–1936)

Food stamps issued by Vilnius City magistrate, 1919, lithograph on paper

Wacław Gizbert-Studnicki, ‘Vilnius’, 1936

The front cover by Janusz Tlomakowski

The 350th anniversary of the founding of the university in Vilnius was a great occasion for the city, and brought it much well-deserved attention. Stephen Báthory University, which in the interwar years continued the traditions of Vilnius University, was an unquestionably important centre of academic and cultural life. Like Dilka’s poster We were born Lithuanians…, in which the artist placed President Smetona next to King Vytautas, works that were made for the jubilee year of the Polish university showed Józef Piłsudski next to the university’s founder Stephen Báthory. The present is compared with history, and the leaders of the interwar states are portrayed symbolically as successors to the work of heroes of the past, as the inheritors of their historical and cultural legacy. Józef Piłsudski chose to have his heart buried in the Rasos Cemetery in Vilnius, a decision that was clearly inspired by Władysław IV Vasa, the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, whose heart rests in Vilnius Cathedral.

Henryk Giedroyc (1904–1942)

The medal commemorating the 350th anniversary of the foundation of Stephen Báthory University, 1929, bronze, Ø – 5,5

One of the main arguments Poland used in support of its claim to Vilnius was the 1919 liberation of the city from the Bolsheviks. This event often appears in works of art. The cover Ruszczyc designed for the publication Wilno I Ziemia Wilenska, about the history, culture and politics of Vilnius and its region, showed a wing with broken chains, symbolically emphasising the liberation of the city. The Lithuanian press, however, took it far from favourably. Naujoji Romuva responded: ‘No, it is not Vilnius that is free, but the city’s unworthy occupants that are free in Vilnius. Does the little cross attached to the miracle-working image of the Virgin Mary of the Gates of Dawn have no meaning when it says: “Take us back to Lithuania”?’

Bolesław Bałzukiewicz (1879–1935)

Design for a poster commemorating the anniversary of regaining Vilnius, 1920s

Etching on paper, 30 × 24,5

Kaunas Art School

After the reestablishment of statehood, most Lithuanian artists were concentrated in Kaunas. In the 1920s, they looked after the organisation of artistic life themselves. The Lithuanian Art Creators’ Society was founded in 1920. Its members started organising group exhibitions and drawing classes (classes were later organised by the Ministry of Education), laying the foundations for Kaunas Art School. One of the central figures in the development of art education in Kaunas was the painter Justinas Vienožinskis, the founder of the drawing classes, who had studied at Cracow Academy of Art.

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

Justinas Vienožinskis (1886–1960)

Portrait of the children of the artist’s brother Apolinaras Vienožinskis, 1932

Oil on canvas, 60 × 80

Unknown artist

The consecration solemnity of the construction works of an art school, May 8, 1923, Kaunas, photograph

The wall of the ‘Salon’ (in keeping with the interwar tradition of displaying art) shows work by the Kaunas Art School teachers Vladas Didžiokas, Jonas Mackevičius, Justinas Vienožinskis, Petras Kalpokas, Antanas Žmuidzinavičius and Juozas Šileika. The sculpture Day and Night is by Petras Rimša. In the 1930s, exhibitions were still dominated by Realist art, interwoven frequently with echoes of the ideals of Romanticism. Visitors liked art in a conservative style, and they bought it willingly.

View of the exposition

Vladas Didžiokas (1889–1942)

Portrait of Antanas Smetona, President of the Republic of Lithuania, 1930s

Oil on canvas104,5 × 76

Jonas Mackevičius (1872–1954)

Girls in winter, after 1924, oil on canvas, 1119,5 × 88

Jonas Mackevičius (1872–1954)

Coast of Capri, before 1926, oil on canvas, 36 × 50

Justinas Vienožinskis (1886–1960)

Portrait of Robertas Antinis, 1930s, oil on canvas, 81 × 69

Petras Kalpokas (1880–1945)

Landscape, 1940, oil on canvas, 39 × 59

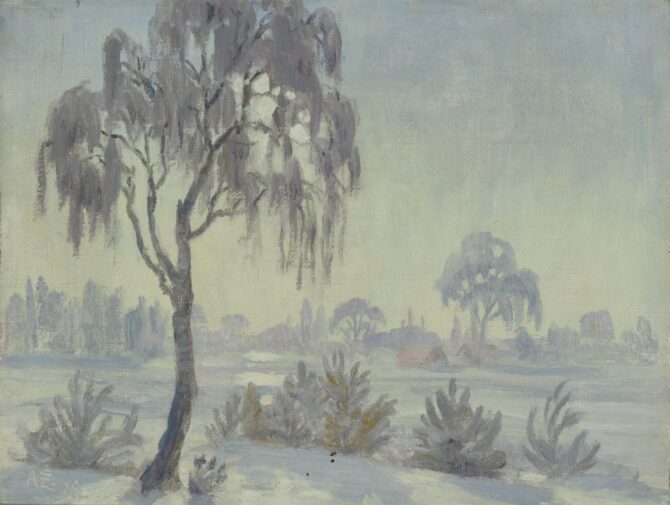

Antanas Žmuidzinavičius (1876–1966)

Trees in white frost, 1938, oil on canvas, 19 × 25

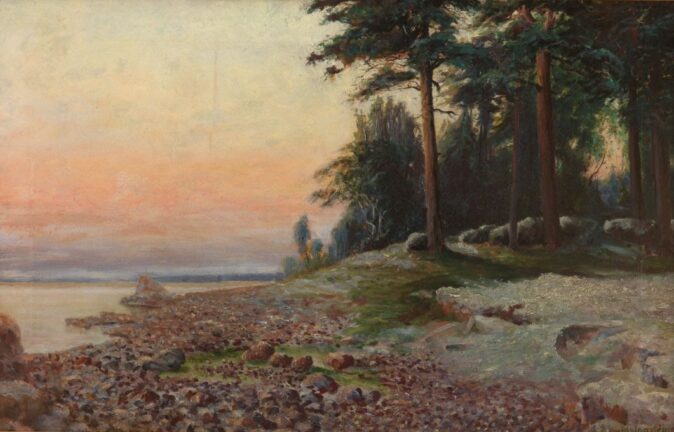

Antanas Žmuidzinavičius (1876–1966)

On the seashore, 1920s, oil on canvas, 53 × 84,5

Antanas Žmuidzinavičius (1876–1966)

Cross-eyed girl from Meteliai, 1926, oil on canvas, 46 × 37

Jonas Šileika (1883–1960)

Village in the valley, 1924, oil on canvas, 50 × 71

Petras Rimša (1881–1961)

Day and night, 1922, bronze, h – 51,5

The older-generation artists who aspired to create a national art did not introduce any particular stylistic innovations during the 1920s and 1930s. They worked in the style of Realism, and used the discoveries of Early Modernism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and Symbolism. These trends dominated the curriculum at Kaunas Art School at the beginning. Stylistic and generic shifts were brought about by the generation who came of age in the 1930s. They were not happy with the old-fashioned teaching methods, and sought to reinvent means of expression in art. The tone of exhibition reviews was also new, for art critics started calling for a more contemporary visual language.

View of the exposition

The second half of the 1930s was marked by polemics between the Realists of the older generation and artists who had studied abroad. They separated, exhibited at separate events, and new art groups sprung up. The spread of European art trends resulted from the return to the interim capital by Kaunas Art School graduates after studying abroad. Two major stylistic trends consolidated in the 1930s: the Ars movement, and the school of Stasys Ušinskas.

Members of the Ars group tended towards emotionality, Expressionist rendition, and uneven textures in their canvases. They turned deliberately to folk art, and found inspiration in nature. The neo-traditional school of Stasys Ušinskas was characterised by the Art Deco style, and by motifs in logical compositions, preferring studies of the human figure to nature. Painting diversified in terms of genre, too. In addition to portraits and landscapes, and the occasional historical paintings favoured by older artists, genre compositions, still-lifes and religious paintings also appeared.

View of the exposition

The 1932 exhibition of works by the Ars group, the most prominent Modernist group in Lithuania, featured work by the sculptor Juozas Mikėnas, the painters Antanas Gudaitis, Antanas Samuolis and Viktoras Vizgirda, and the graphic artists Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas, Telesforas Kulakauskas and Jonas Steponavičius. Professors Adomas Galdikas and Mstislav Dobuzhinsky also took part in supporting the young artists. The event was accompanied by a theoretical statement of artistic principles, soon to become known as the ‘Ars Manifesto’. It declared: ‘After considering our situation, we are convinced that the absence of deeper explorations in art, and the imitation of worn-out artistic forms, is killing our art. We have resolved to serve the time of the homeland’s renaissance, and to create a style for the epoch.’ The second Ars exhibition in 1934 featured the same participants, but without Dobuzhinsky.

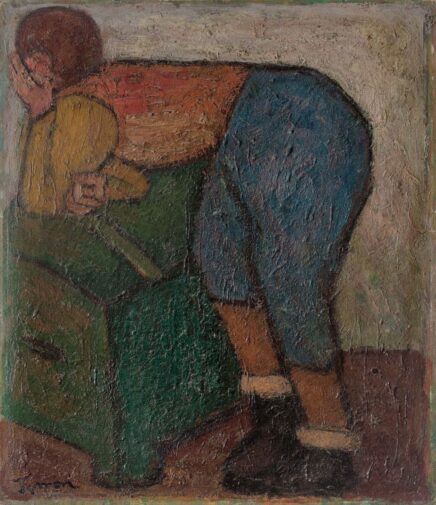

Antanas Gudaitis (1904–1989)

Woman and a girl, 1933, oil on canvas, 72 × 53,5

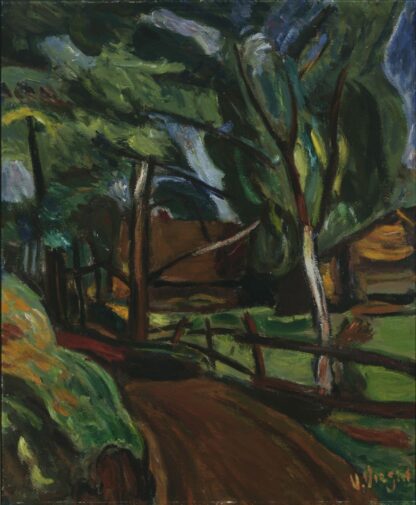

Viktoras Vizgirda (1904–1993)

In Višakio Rūda, 1930s, oil on canvas, 59,5 × 49

Adomas Galdikas (1893–1969)

Prayer, 1920s, oil on canvas, 129 × 53,4

Antanas Samuolis (1899–1942)

With a basket, ca 1926, oil on canvas, 116,5 × 69

Juozas Mikėnas (1901–1964)

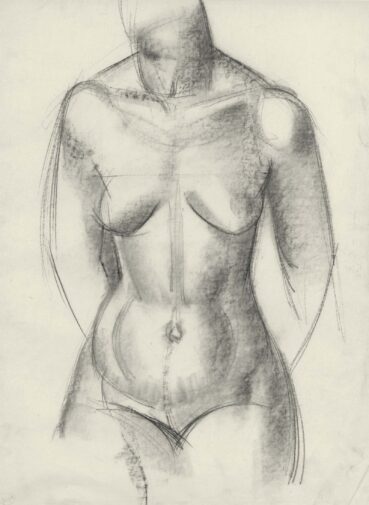

Woman’s torso, ca 1930, charcoal on paper, 56 × 43,7

Juozas Mikėnas (1901–1964)

Female nude, ca 1930, charcoal on paper, 62,4 × 48,2

Juozas Mikėnas (1901–1964)

Thunder, 1934, plaster, h – 75

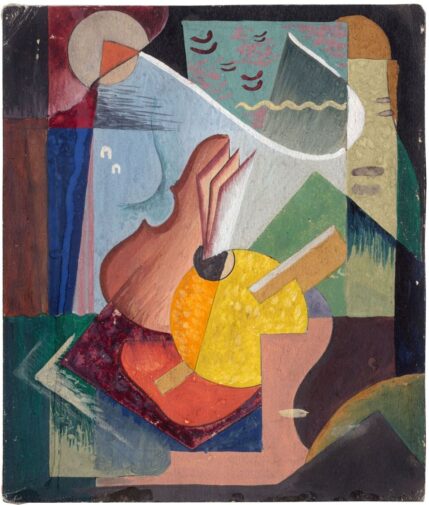

Stasys Ušinskas’ work and his teaching activities were a major impetus in the development of Lithuanian art. This alumnus of Kaunas Art School returned in the early 1930s after studying in Paris, where he specialised in set design and applied art at the National Conservatory of Arts and Crafts, enhanced his painting skills at the Académie Moderne under Fernand Léger, and improved his skills in scenography under Aleksandra Exter. He held a solo exhibition in the autumn of 1931, at which he presented what he had learned in Paris, hitherto almost unseen by local people. His compositions in the style of Cubism, Constructivism and Art Deco received lavish attention and critical acclaim. In the second half of the 1930s, like most of his colleagues seeking state support, Ušinskas turned from avant-garde innovation to Neoclassicism, as a style that was more highly rated and more suitable for state commissions. As an art teacher, Ušinskas prepared a new generation of artists in the monumental decorative arts and scenography. One of his most famous students, Kazys Varnelis, developed Art Deco stylistics in his work of the early 1930s.

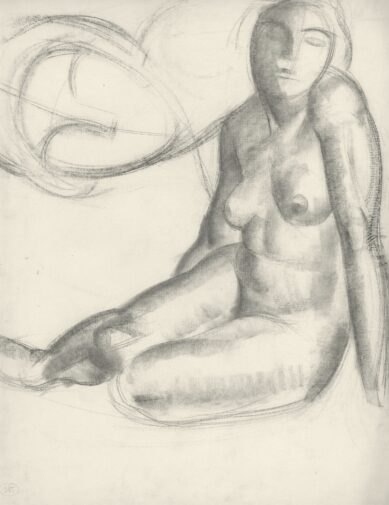

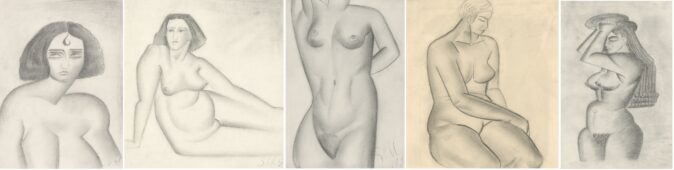

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

Nude studies, 1930–1932, charcoal on paper

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

Circus rehearsal (plafond), before 1940, oil on canvas, 220 × 236

Kazys Varnelis (1917–2010)

Battle of Rudau, before 1943, oil on canvas, 116 × 250

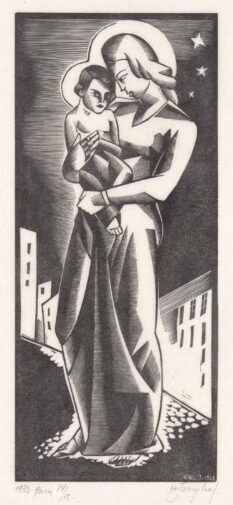

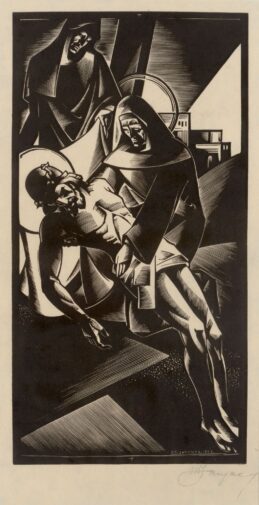

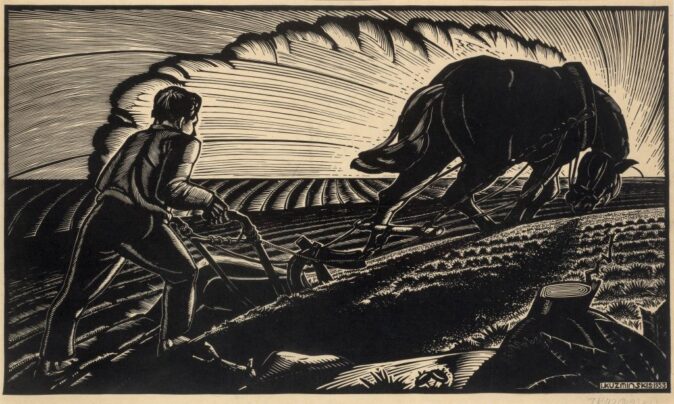

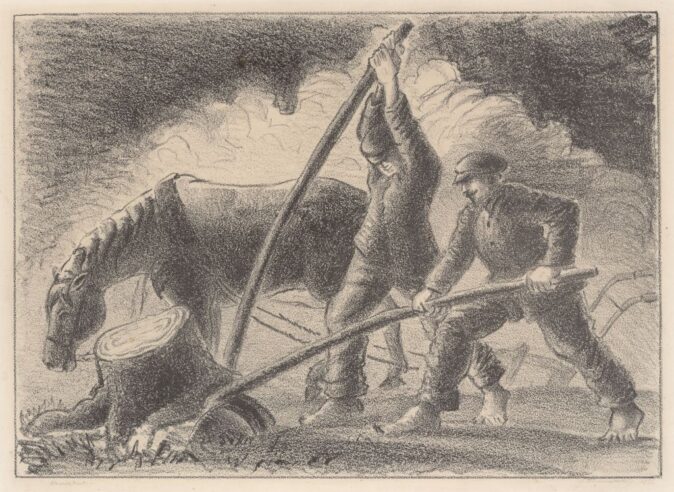

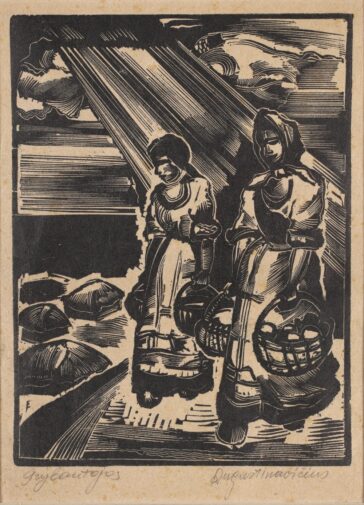

Kaunas Art School started teaching graphic art in 1923. The Graphic Art Studio opened in 1926, headed by Adomas Galdikas. From 1929 to 1930, it was headed by Mstislav Dobuzhinsky. Galdikas and Dobuzhinsky were open to artistic innovation and the influence of Modernism, and tried to instil it in students in the Graphic Art Studio. Galdikas encouraged students to find forms of expression in folk art. He sought interpretation, not imitation, and advised students to combine traditional forms of expression with the most modern trends in art (the ideals of the Ars movement). The work by young graphic artists in the second half of the 1930s was therefore dominated by Art Deco, Neoclassicism and neo-traditionalism, which offered more freedom in paraphrases of folk art.

Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas (1907–1997)

Madonna in the street, 1933, woodcut on paper, 30,6 × 21,5

Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas (1907–1997)

Descent from the cross, 1933, woodcut on paper, 32 × 16,8

Jonas Kuzminskis (1906–1985)

Ploughman, 1933, woodcut on paper, 42 × 64

Jonas Kuzminskis (1906–1985)

Settlers, 1936, autolithograph on paper, 36 × 26

Paulius Augius-Augustinavičius (1909–1960)

Mushroom pickers, 1941, linocut on paper, 17,8 × 13,5

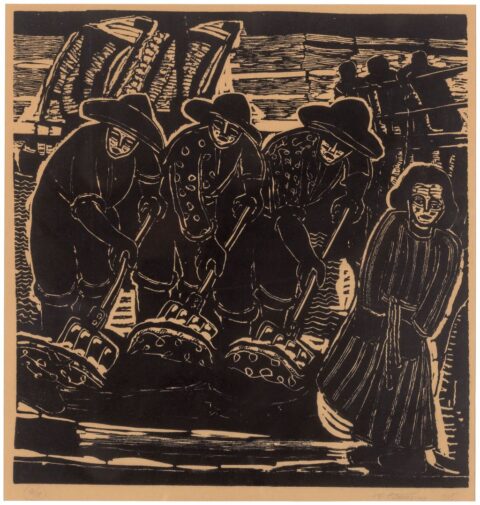

Viktoras Petravičius (1906–1989)

A fisherman’s family, 1935, woodcut on paper, 39,5 × 36

Outside the mainstream

This room presents work that was outside the mainstream, and artists whose activities were not directly related to Kaunas Art School or the Faculty of Art at Stephen Báthory University. For example, Paris by Neemija Arbit Blatas is displayed in the storage area. He never studied at Kaunas Art School. After graduating from a gymnasium in Kaunas, he studied in Berlin and Dresden from 1924 to 1926, and afterwards in Paris, at the Académie Julian and the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. Blatas opened the first private art gallery in Kaunas, where he put on exhibitions of work by young artists, both Lithuanian and other nationalities (mostly Jewish), in 1932 and 1933. He closed the gallery due to a lack of resources, and left for Paris. He settled in New York in 1940. After the Second World War, he lived in New York, Paris and Venice.

Arbit Blatas (1908–1999)

Paris, 1930s, oil on canvas, 73 × 91,5

Stefan Römer came from a famous noble family, and occasionally exhibited in Kaunas during the interwar period. He lived in Vilnius and on the Bagdoniškis estate in the Rokiškis district. He was self-taught in art. In 1927, with help from the lawyer Mykolas Pijus, Römer went to Prague to study for several years. His decorative painting Michaś Mieczkowski, in a style close to Vilnius Neoclassicism, was shown in 1935 and 1936 at the First Autumn Art Exhibition in Kaunas. Most of his works were lost to fire in the Second World War, and are now rarely found in Lithuanian museums and private collections.

Stefan Römer (1900–1951)

Michaś Mieczkowski, 1929, oil on canvas, 78,5 × 50

A portrait of a female nude with a cigarette by Ada Peldavičiūtė-Montvydienė is displayed next to Römer’s work. The elegance of its elongated forms, and the provocative nudity and the cigarette in the hand, are unusual for Lithuanian painting of the period. The style establishes a parallel with the Art Deco work by the famous American of Polish origin Tamara de Lempicka.

Ada Peldavičiūtė-Montvydienė (1911–1967)

Nude woman with a cigarette, 1934, oil on canvas, 82 × 55

View of the exposition

Among the sculptural works created in Lithuania in the interwar years, the woodcarvings of symbolic figures (mostly busts) by Matas Menčinskas stand out by their ingeniousness. Menčinskas entered Kaunas Art School in 1922 before the Sculpture Studio there opened, and soon had to look for opportunities to study abroad. He went to Barcelona, Madrid, and finally to Buenos Aires in South America. There he became interested in the work of a friend of his, a sculptor of Russian origin known by his nickname Erzia (his full name was Stepan Nefedov). Erzia had a strong influence on Menčinskas’ style, and also on his choice of material (usually quebracho wood). Financial hardship and failing health made him return to Lithuania in 1934. His unusual pieces carved in wood struck a chord with their technical skill and expressive power, unlike the prevailing creations in clay, gypsum and bronze. However, he did not avoid the influence of Art Deco either, and created figures in Neoclassical forms, as well as high-quality salon-style compositions in gypsum.

Matas Menčinskas (1897–1942)

Head, 1929–1934, wood, h – 51

Another important influence in shaping stylistic trends and spreading Modernism in the interwar years was the work and activities of Vytautas Kairiūkštis. He lived in Vilnius from 1921 to 1932 but did not teach at Stephen Báthory University, and was very sceptical about the work by the teaching staff in the Faculty of Art, except perhaps for that of the famous Polish Modernist Zbigniew Pronaszko. He did not participate in any of their organisations or exhibitions. His style differed significantly from the prevailing Neoclassicism. Kairiūkštis kept in very close contact with Lithuania and Kaunas. He collaborated with the Keturi vėjai movement in the 1920s, and in 1931 he organised an exhibition in Kaunas of work by Vilnius-based Lithuanian artists, at which they presented abstractions, compositions in the manner of Cubism, Futurism and Constructivism, and photomontages.

Kairiūkštis was well connected internationally as an interwar painter, art historian, teacher and exhibition organiser, and cultivated links with foreign art movements and groups. In 1923, together with the Polish artist Władysław Strzemiński, he organised the Exhibition of New Art (Wystawa Nowej Sztuki) in Vilnius, introducing visitors to avant-garde art, with examples of Cubism, Suprematism and Constructivism. It was the first avant-garde event in this part of what was then Poland. After the Nowej Sztuki exhibition, he remained in touch with Polish avant-gardists. Participants in the exhibition, who included Kairiūkštis, formed the nucleus of the Polish avant-garde group Blok. He took part in the first Blok exhibition in Warsaw in 1924. He was also acquainted with the famous Italian Futurist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, the ideological founder of Futurism and author of Manifeste de Futurisme, and Enrico Prampolini, an artist and editor of the Italian Futurist magazine Noi. Kairiūkštis corresponded with Prampolini in the hope of establishing links with Rugger Vasari (the Italian poet and playwright, and editor of Der Futurismus, published in Germany).

Vytautas Kairiūkštis (1890–1961)

The bather, 1930, oil on canvas, 26 × 20

Kairiūkštis’ participation in Lithuanian circles in Vilnius was mainly through the drawing studio based in the Vytautas the Great Gymnasium, a centre for Lithuanian culture and patriotism. He instilled an interest in Constructivism in the young people who attended his drawing classes, in what was at that time the only Lithuanian gymnasium in Vilnius under Polish rule. Among his pupils was Vaclovas Kosciuška, whose early work was strongly influenced by the Constructivist and Art Deco styles that were encouraged by his teacher. Kosciuška learned studied under Kairiūkštis while he was at the Vytautas the Great Gymnasium, but afterwards left to pursue his studies in Kaunas (from 1929 to 1935). After graduating, he spent two years doing military service, but did not give up art, and carried out commissions for the Vytautas the Great War Museum. With the help of the director of the museum Vladas Nagevičius, he won a scholarship from the Kaunas Garrison Officers Club, and subsequently from the Ministry of Defence, and pursued his studies in battle scene painting in Paris from 1937 to 1940. The work of Vaclovas Kosciuška, an artist who is connected with Lithuanian culture in Vilnius, spans many different styles, from decorative stylisation and Art Deco to Realism and Impressionism.

Vaclovas Kosciuška (1911–1984)

Still-life, 1930, gouache on paper, 19 × 16,5

Vaclovas Kosciuška (1911–1984)

At the table, before 1945, oil on canvas, 22 × 28,5

View of the exposition

The Faculty of Art at Stephen Báthory University I

When Vilnius University reopened in 1919 as Stephen Báthory University, Ferdynand Ruszczyc (1870–1936), an influential and dynamic figure in the city’s cultural life, initiated the founding of the Faculty of Art. He saw the faculty as a successor to the tradition of Vilnius University. He stressed the importance to the country’s cultural life of historic figures such as professors Franciszek Smuglewicz, Jan Rustem and Laurynas Gucevičius. The newly opened faculty was expected to combine scholarship with art, and to contribute to the flourishing of the Vilnius region.

It is natural that the focus on history and tradition encouraged a rather conservative approach to art and studies. Part of the Bernardine friary was chosen as the premises for the new faculty for good reason. According to Ruszczyc, a modern building would not be suitable for an establishment that was to ‘bring together young artists capable of appreciating the charisma of Vilnius, who would feel inspired to foster everything about it that has been preserved, in order to create art from the same source’. The curriculum paid much attention to the cultural heritage, and offered a course in the history of art alongside other disciplines. This must have been a major reason for excluding the Constructivist avant-gardists Vytautas Kairiūkščtis and Władysław Strzemiński. The main stylistic trend was Neoclassicism, linked mainly to Ludomir Sleńdziński. The Vilnius version of the style was to dominate art teaching until the closure of the university in 1939.

View of the exposition

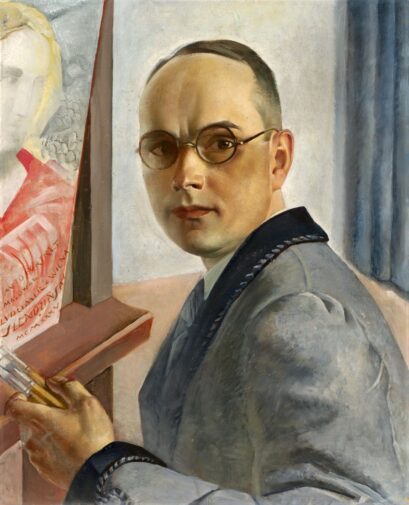

Ludomir Sleńdziński came from an old Vilnius family. Both his father and his grandfather were painters. After studying at the Academy of Art in St Petersburg, from 1909 to 1916 he studied painting under Dmitri Kardovski, a member of the Mir Iskusstva group, an accomplished draughtsman, and an expert in old techniques of painting. In 1923, Sleńdziński joined the group Rytm. The group’s Polish members favoured clear drawing and composition, and a slightly stylised figurative manner of painting. Sleńdziński travelled extensively, and found much inspiration in the Old Masters, especially from the Italian Renaissance. He lived in Italy in 1923 and 1924, later visiting Paris, Spain, England, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey and Palestine.

Ludomir Slendziński (1889–1980)

Self-portrait, 1935, oil on canvas, 57,5 × 47

The Lithuanian National Museum of Art

As one of the most notable Polish adherents of Neoclassicism, Sleńdziński was clearly influenced and guided in his stylistic endeavours by his teacher Dmitri Kardovski, and also by West European and Classical art. His style was orderly and logical, inspired by urban culture, rather than by romantic and unruly nature. His subjects and his stylistic approach had a great influence on university students. His role in the artistic life of Vilnius was not limited to teaching art at the university: he was one of the founders, and became the first head, of the Vilnius Society of Artists.

Adherents of Neoclassicism not only revolted against avant-garde trends, they also opposed Realism, Impressionism and Symbolism. Looking quite often to historical and mythological themes for their inspiration, they transformed Classical forms of art stylistically, tailoring them to their own times. Their subjects also existed in the present: for instance, a woman resembling a Renaissance figure in a painting by Ludomir Sleńdziński (1889–1980) reminds the viewer of the period he belonged to. Sleńdziński chose the Art Deco style, while the powder compact in the woman’s hands is an obvious attribute of the 20th century.

Ludomir Slendziński (1889–1980)

Portrait of a woman, ca 1925, oil on canvas, 69 × 50

The Lithuanian National Museum of Art

View of the exposition

Bolesław Bałzukiewicz (1879–1935)

Sitting woman, 1921, terracotta, 30 × 31

Despite its new approach to traditional genres and themes, Neoclassicism applied traditional formal principles, in terms of composition, the clarity of the drawing, and monumental and idealised forms. Artists took their inspiration from Greek and Roman art, the Renaissance, and 17th and 18th-century Classicism. This naturally led to the predominance of nudes, portraits and figure compositions, surrounded by the architecture of urban settings. For instance, the composition of Laundresses, by an alumnus of Stephen Báthory University, recalls historical painting. The arrangement of the figures against the backdrop of Vilnius architecture transforms a scene portraying a daily chore into an event of sublime grandeur. Admittedly, these artists also applied Modernist trends (Cubism and Expressionism), and experimented with distortions and the expressiveness of the image.

When Ruszczyc had to leave his position in 1932 on account of poor health, he was replaced in the Faculty of Art by Sleńdziński. The position of Neoclassicism was strengthened, but Sleńdziński attracted criticism for his conservative approach to teaching art. Unlike Kaunas Art School, Stephen Báthory University was an institution of higher education, and there was no need to award scholarships to students to study abroad in order to gain a university-level education in art. This consolidated local studies and trends at the university. Students were introduced to artistic trends by professors who had travelled in other European countries, and had studied at schools in St Petersburg, Cracow and Warsaw.

Graduate of Stephen Báthory University’s Faculty of Art

Laundresses (By the Vilnelė in Užupis), before 1939, oil on canvas, 148 × 226

Jerzy Hoppen (1891–1969) (1891–1969)

The courtyard of the Bishops’ Palace, 1925, etching on paper, 16,8 × 22,8

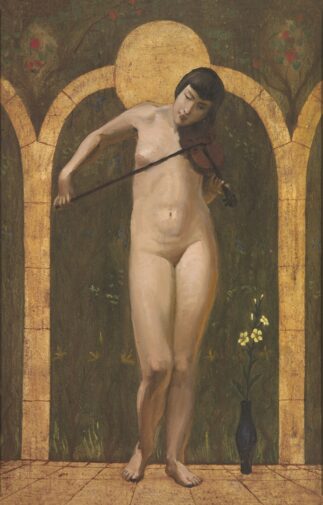

Michał Dobriak (1904–2001)

Violinist, ca 1930, oil on plywood, gilding, 54 × 36

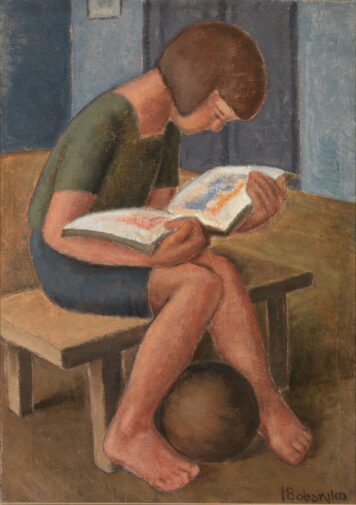

Halina Bobaryko-Modelska (first half of the 20th century–?)

Girl with a book, before 1940, oil on canvas, 67,5 × 48

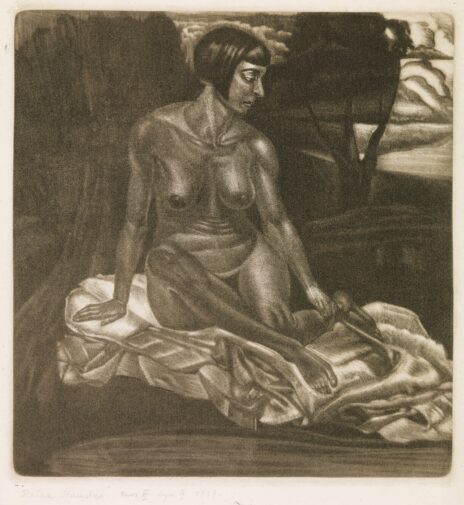

Stanisław Rolicz (1913–1997)

Sitting woman, 1939, etching on paper, 22 × 21

The Faculty of Art at Stephen Báthory University II

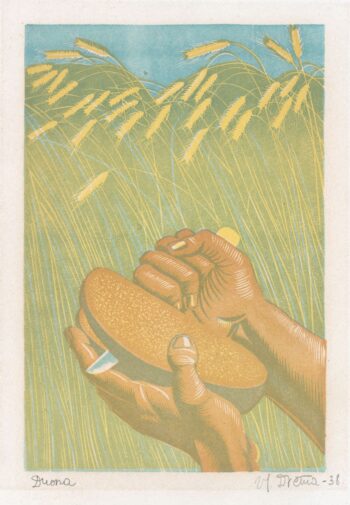

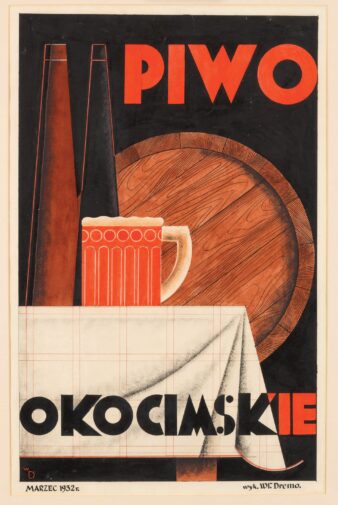

Although the greatest influence on students at Stephen Báthory University was the Neoclassicism encouraged by Ludomir Sleńdziński, this was not the only stylistic trend at the Faculty of Art. Tymon Niesiołowski (1882–1965) offered a different and individual approach, which was characterised by subtle colour schemes and colour-plane compositions. He studied at Cracow Academy of Art, and in Vilnius he taught carpet and poster design. It is likely that Vladas Drėma created his poster for Okocim beer under Niesiołowski’s influence.

Tymon Niesiołowski (1882–1965)

Untitled, 1920s–1930s, oil on canvas, 35 × 30

Vladas Drėma (1910–1995)

Bread, 1938, color linocut on paper, 13 × 19

Vladas Drėma (1910–1995)

Advertisement for Okocim beer, 1932, watercolor, pencil, charcoal, sanguine, ink on paper, 75 × 48

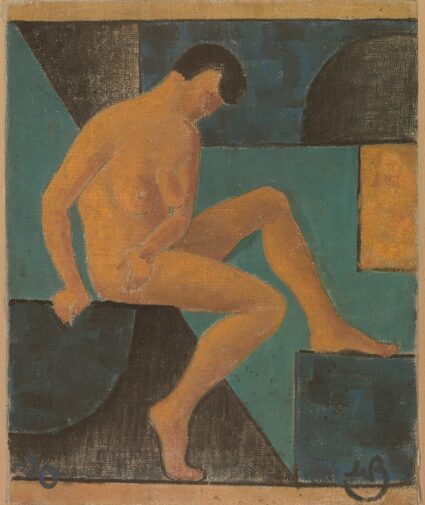

Drėma, who started his art studies in a milieu dominated by Vytautas Kairiūkštis, opted for a style of expression that inclined towards Constructivism. A figure study by an unknown student from Stephen Báthory University shows the same tendencies.

Student of Stephen Báthory University’s Faculty of Art

Study of figure, 1930, oil on canvas, 58,5 × 48

View of the exposition

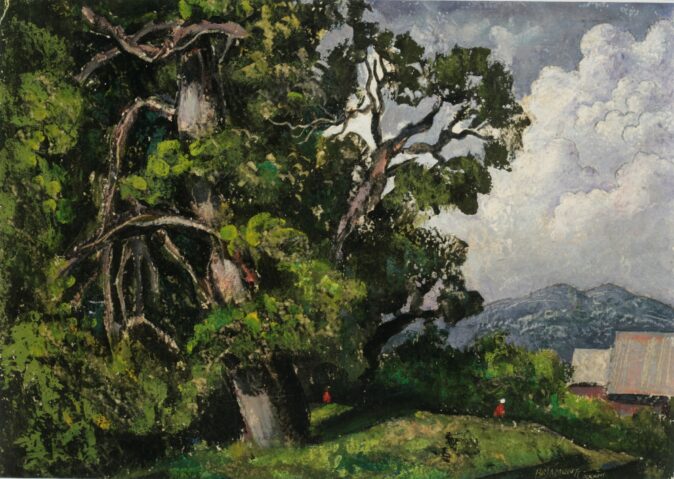

However, Bronisław Jamontt (1886–1957) clearly distanced himself from Neoclassicism. He studied as an external student at the Academy of Art in St Petersburg, and was considered the successor to Ferdynand Ruszczyc as a leading landscape painter. He can be classed as a Neoromantic. His landscapes, made up of stylised shapes, often combined urban views with motifs from nature, thus creating an unsettling atmosphere and a mystical image of the city.

Bronisław Jamontt (1886–1957)

Vilnius landscape with old oaks, 1932, tempera on cardboard, 64 × 79

Bronisław Jamontt (1886–1957)

Landscape with trees, 1933, oil on cardboard, 24,5 × 34

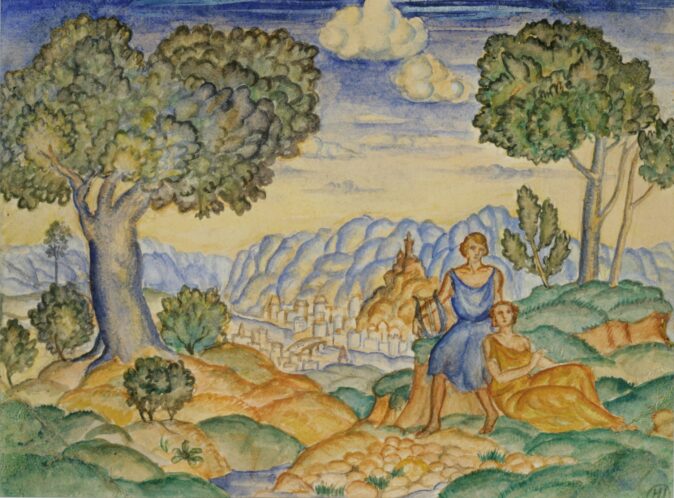

A mystical atmosphere was also characteristic of works in the Neoclassical style. They show a rather utopian environment rather than real life. In their compositions, these paintings resemble mythological or historical scenes. For instance, a provincial idyll in a graduation work by Koźma Czuryło has a clear affinity with the fête galante of 18th-century French Rococo.

Koźma Czuryło (1908–1951)

Composition (Graduation work of Stephen Báthory University’s Faculty of Art), 1936, oil on canvas, 148 × 226

View of the exposition

Jerzy Hoppen (1891–1969)

Landscape with human figures, 1920s–1930s, watercolor on paper, 13 × 17

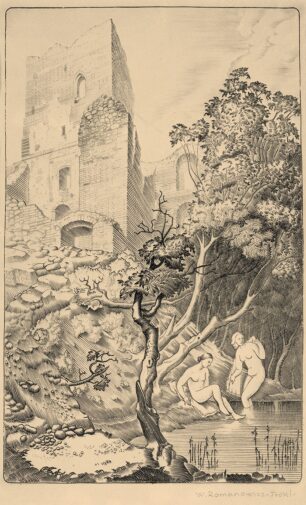

Walenty Romanowicz (1911–1945)

Bathers in the lake at Trakai, 1940, copper etching on paper, 24 × 15

Although the artistic talent of Ludomir Sleńdziński, the leading exponent of Neoclassicism, was undisputed, there were artists who wanted to distance themselves from his influence, to the point of leaving the Vilnius Society of Artists. The Independent Artists’ Society was created in 1931. Among its members were some rather conservative artists (Eugeniusz Kazimierowski, Mariana Kulesza and Piotr Hermanowicz), as well as some who pursued stylistic innovation, such as Leona Szczepanowiczowa, Waclaw Czechowicz and Jozef Horyd. The display includes a painting by Waclaw Czechowicz that is uncharacteristic of his style, and closer to Neoclassicism. Unlike in Kaunas, artists in Vilnius formed different societies not because of the generation gap, but in an effort to counterbalance the influence of Ludomir Sleńdziński.

Wacław Czechowicz (apie 1880–po 1965)

Love song, 1928–1930, oil on canvas, 24,5 × 34

Art of the Second World War

The Second World War is the least researched period in Lithuanian Modernist art. On one hand, the work from this time reflects the grim and apprehensive wartime mood; and on the other hand, the change in artists’ circumstances introduced new subjects and a new personal perspective. Artists did not stop working under the Soviet and Nazi occupations, but had to put up with material and psychological hardships, and also had to pass the censors.

View of the exposition

Algirdas Petrulis (1915–2010)

Woman with a mirror, 1943, oil on canvas, 81 × 61

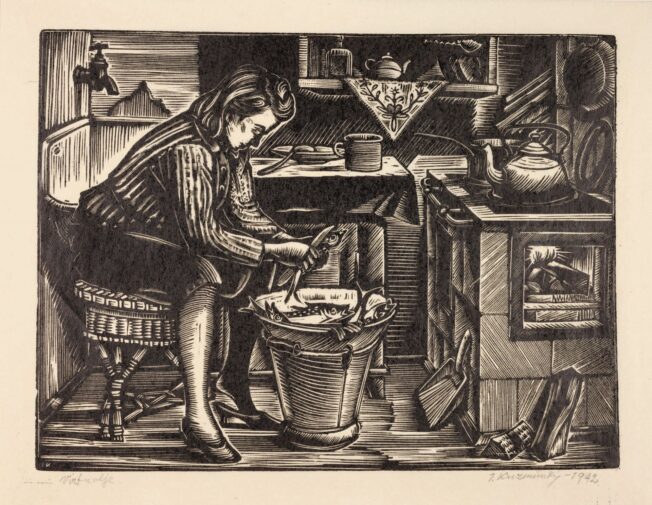

Jonas Kuzminskis (1906–1985)

In the kitchen, 1942, woodcut on paper, 19 × 23,5

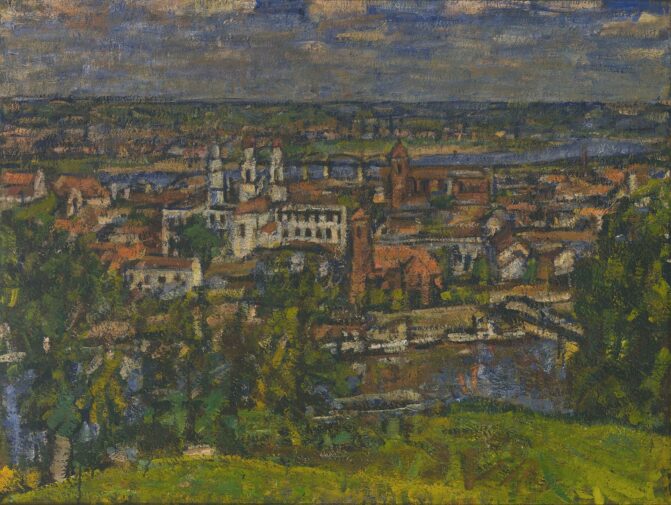

After Stephen Báthory University was closed in 1939, Vilnius Art School opened in the premises of the old Faculty of Art on 14 June 1940. A year later, it was transformed into Vilnius Academy of Art. Justinas Vienožinskis, Viktoras Vizgirda, Antanas Gudaitis and Jonas Kuzminskis came to Vilnius from Kaunas to work at the academy, while the school in Kaunas offered only courses in applied art. Adherents of the dominant Kaunas trend, who had used expressive brushwork and stressed the importance of colour, and who had looked for inspiration in nature and the countryside, now discovered urban views in Vilnius. Inspired by the Polish pictorialist tradition shaped by Jan Bulhak, they juxtaposed iconic architecture with verdant parts of the city, creating a style that redefined the iconography of the city. This differed from the work of the Polish school, which emphasised drawing over painting, and in which Vilnius often appeared as a romantic and occasionally mystical city of great historical value with a glorious past. A typical view of wartime Vilnius in the style born in Kaunas is Old Vilnius motif by Antanas Gudaitis. Landscape was the most widespread genre during the wartime years. It was ideologically neutral, acceptable to the censors, and therefore often exhibited and gladly bought by the public. For Lithuanian artists, an idealised view of Vilnius was also a link with the regained historical capital and a demonstration of their right to it, so there is an almost joyful mood in these views.

Antanas Gudaitis (1904–1989)

Old Vilnius motif, 1942, oil on canvas, 92 × 73

A common feature of wartime art by Lithuanian and Polish artists was the unsettling and melancholic mood bred by uncertainty about the future, and by personal and social tragedy. Even Jonas Šileika, who was usually quite consistent in his moderate style, started to experiment, searching in his uncharacteristic landscapes for signs in the sky.

Jonas Šileika (1883–1960)

A sign in the sky (observed by the artist in 1931, eastwards from the ancient cemetery of Jadagoniai), 1943, oil on canvas, 60,5× 72

Polish artists found themselves in a more complex predicament than the Lithuanians. After the closure of Stephen Báthory University, many of its professors could not find work with institutions that were founded by the Soviet authorities. Some had to look for an alternative source of income. Artistic life did not stop, but it was dominated by Lithuanian artists who operated as members of the Lithuanian Artists’ Union, the rules of which had been established by the Soviet and Nazi occupying authorities. The Nazi authorities put restrictions on artists of Slavic origin, limiting their activities and their opportunities to exhibit. However, this did not mean that Polish artists stopped creating. Most professors and former students from the university lived in Vilnius until 1946 or 1947, when they had to move to Poland, taking Vilnius art traditions to Gdansk, Toruń and other Polish towns. An intimate and melancholic view of Vilnius can be seen in Stanisław Rolicz’s painting A House at Night.

Stanisław Rolicz (1913–1997)

A house at night, 1943, oil on cardboard, 55 × 71

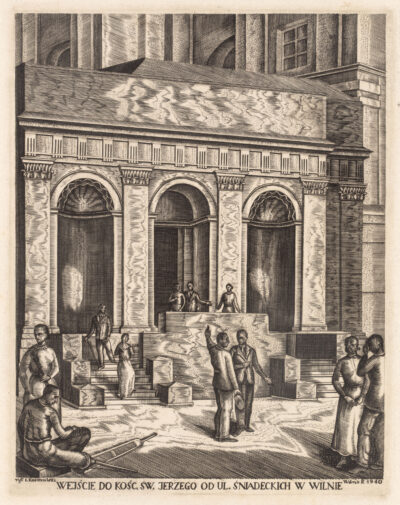

Leon Kosmulski (1904–1952)

The entrance to the Church of Saint George from Sniadeckich Street, 1940, etching on paper, 30 × 24,6

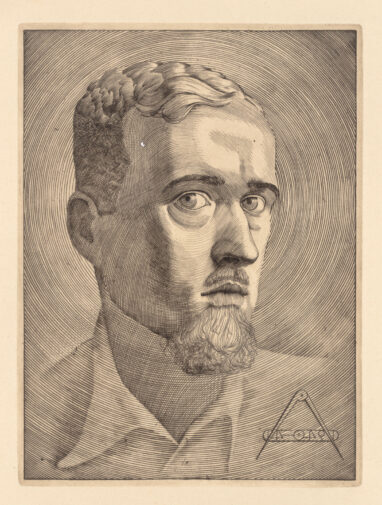

Walenty Romanowicz, who studied both art and medicine before the war, depicted himself in a circle drawn with a compass like a 20th-century Vitruvian man, looking dramatically at the absurdity of war.

Walenty Romanowicz (1911–1945)

Self-portrait, 1942, copper etching on paper, 17,5 × 13

Inspired by American Regionalism and by Grant Wood, Filomena Ušinskaitė portrayed her uncle, a returned emigré from the United States, whose life ended sadly in Soviet-occupied Lithuania.

Filomena Ušinskaitė (1921–2003)

Uncle, 1944, tempera on cardboad, 100 × 120

View of the exposition