The fourth TARTLE exhibition – Free and Unfree. Lithuanian Art between 1945 and 1990

In its fourth exhibition, the Lithuanian Art Centre Tartle showcases part of its collection representing the tendencies in artistic life in Soviet-occupied Lithuania, and features of the work by artists who fled to the West. In Lithuania, the period was distinguished by the efforts by artists to adapt or find a way around the requirements the Soviet authorities placed on art; and in the work by émigré artists of the time, creative freedom was combined with the aim to preserve Lithuanian traditions.

The works on display are by artists who are traditionally associated with the golden age of Lithuanian art in the second half of the 20th century. They include Silvestras Džiaukštas, Vincentas Gečas, Antanas Gudaitis, Vincas Kisarauskas, Leopoldas Surgailis, Stasys Ušinskas and Kazė Zimblytė. Representatives of émigré and Litvak art include Arbit Blatas, Pranas Domšaitis, Jacques Lipchitz, Jonas Rimša, Elena Urbaitytė-Urbaitis, Kazys Varnelis and Kazimieras Žoromskis. The paintings, sculptures, graphic works and glass reflect not only the aesthetic side of art, but also aspects of the cultural and social contexts of this complex period.

The first rooms in the gallery focus on the influence of the social situation and the political changes on the artistic language and stylistics of Soviet-period art. They emphasise the role of official propaganda, which demanded that art be ‘national in form and socialist in content’, and include images of collective farm workers having lunch, the Church of St Casimir without its cross, a concert given by the Lietuva song and dance ensemble, and variations on the theme of the popular folk tale ‘Eglė, Queen of the Serpents’. The exhibition draws attention to the change in artistic style: from pure Socialist Realism to the search for an individual style, and the process of the modernisation of art that started in the period of the political ‘thaw’.

Other rooms display works that illustrate tendencies in the creative work of artists who fled from Lithuania: some adapted to the prevailing local artistic traditions, in an attempt to gain a foothold in their new country, others preserved their Lithuanian identity, and some managed to both preserve their identity and adapt to new ideas. The display highlights the phenomenon of the Freiburg School of Arts and Crafts in the postwar years, the cultural activities of émigré communities, and the individual choices of artists, and also looks at certain features of the work of Litvak artists.

The exhibition invites visitors to view the multi-faceted micro-narratives and macro-history of the second half of the 20th century through art. It includes 80 paintings, works of graphic art, sculptures, glass, ceramics and prints from the Tartle collection. One painting has also been lent for the exhibition by the Mo Museum.

Dovilė Barcytė, Ieva Burbaitė, art historians and exhibition curators

Photo credits: Andrius Stepankevičius, Antanas Lukšėnas

Video author: Edvardas Volginas

read more

Socialist in content and national in form

The first room presents the theme of changes that occurred in the Lithuanian art scene after the war in the repressive Stalinist period. Soviet ideology placed much importance on the propaganda function of art, and the Artists’ Union became the main tool to exercise control over artists, their works, and their promotion. This institution was in charge of the content of creative work, i.e., the “education” of artists, censorship of their works, exhibitions, and state commissions. It supervised what could be put out for exhibitions and in what form, and what visual environment the residents of the occupied country were exposed to.

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

In the first post-war decades, in ideologized Soviet art primary importance was placed on a clear and easily understandable image and narrative; thus, not surprisingly, artists were required to use the stylistics of realism and a heroic narrative praising the achievements of the Soviet system. Though, on one hand, an explicit socialist content was required, on the other, efforts were taken not to make art completely repulsive to the audiences of the occupied countries. Artists were allowed to retain a certain degree of autonomy and to use ethnic motifs. Thus, art had to be “socialist in content and national in form”, and Lithuanians were a nation but by no means an independent state.

Art exhibition catalogue, Vilnius: The Union of Soviet Artists of the Lithuanian SSR, 1946

Domicelė Tarabildienė (1912–1985)

A folk song, 1972, linocut on paper, 36,5 x 24

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

The May holiday, ca. 1970, mixed media on paper, 45 × 55

Robertas Antinis (1898–1981)

The piper, 1960s–1970s, chamotte, h – 22

Jonas Kuzminskis (1906–1985)

Illustration for the poem ‘Eglė the Queen of Serpents’ by Salomėja

Nėris, 1945, woodcut on paper, 16,5 × 14

Robertas Antinis (1898–1981)

Eglė, the Queen of the Serpents, 1957, plaster

Juozas Kėdainis (1915–1998)

Illustration for the novel ‘Frank Kruk’ by Petras Cvirka, 1947, pencil and ink on paper, 25,6 × 18,2

Jonas Kuzminskis (1906–1985)

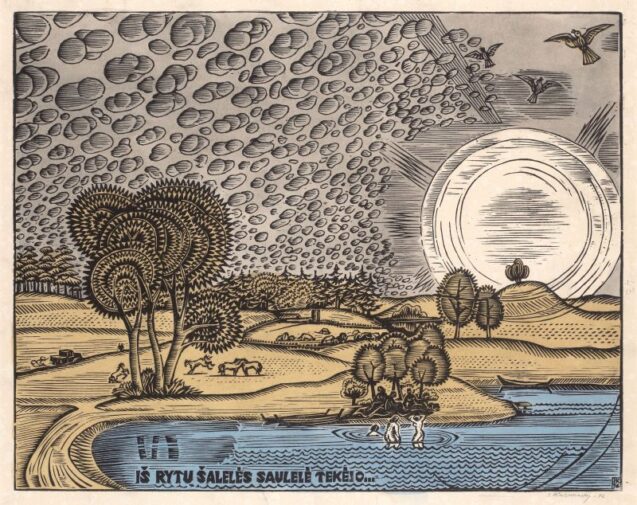

The sun rose from the east…, 1976, colour woodcut on paper, 38 × 47

Interwar modernist artists after the war had to adapt to the new requirements set not only for the contents of the works, which must have appealed to very few of them, but also for the form. The Lithuanian school of art was characterized by modernist rather than realist tendencies; thus, it was not so easy for the artists to change course. For example, Stasys Ušinskas after the war focused on teaching activity and applied art, which was subject to less strict requirements than a prestigious art form – painting. An interesting example in this context is his “Project of an Allegoric Panel on the Theme of Work”. Here, the artist follows the official requirements by the book, representing the new socialist Lithuania naively and, most likely, ironically. The work is indeed “socialist in content and national in form”, but it is obvious that it would not have passed Soviet censorship both because of its obvious insincerity or artificiality, and because of its stylistics reminiscent of interwar artistic tendencies. The painting Tractor Drivers’ Lunch by Piotr Sergiyevich seen in this exhibition demonstrates what was actually required by Soviet censorship when representing collective farm workers life.

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

A sketch for a panel on the theme of work, before 1960, tempera on paper, 52 × 81

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

Allegorical composition with planets and Signs of the Zodiac on the theme of the conquest of space, 1964, mixed media on paper, 55 × 75

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

Decorative vase ‘Palanga’, 1970, glass, h – 29

Filomena Ušinskaitė (1921–2003)

Vase ‘The Orphan’ (‘Sigutė’), 1960, glass, glaze, silver overlay, h – 25,7

Filomena Ušinskaitė (1921–2003)

Vase ‘Autumn’ (‘Picking apples’), 1959, glass, glaze, silver overlay, h – 36

Petras Sergijevičius (1900–1984)

Tractor drivers’ lunch, 1957, oil on canvas, 97 × 138

View of the exposition

A typical work of Soviet realist art is Vilnius Landscape with Casimir’s Church by Vytautas Mackevičius (ca. 1970). Though the painting is somewhat melancholic and apparently does not represent the flourishing Soviet life, it excellently represents the years of the occupation – St Casimir’s Church, the oldest Jesuit temple in Vilnius, was converted into the Museum of Atheism in 1961, and the building is depicted already stripped of its crosses. Thus, it is an obvious example of the Soviet antireligious policy. Artworks well illustrate the attempts to change and construct Lithuanian identity, and to promote a new type of a perfect Lithuanian – a resident of the occupied country, a subservient non-religious peasant dependent on the community.

Vytautas Mackevičius (1911–1991)

Vilnius townscape with St Casimir’s Church, ca. 1970, oil on canvas, 146 × 200

Excerpt from the film chronicle ‘Soviet Lithuania No.6’, 1949. Director Steponas Uzdonas, director of photography Leonas Tautrimas, Lithuanian Film Studio

The opening of the art exhibition held in honour of the 6th Congress of the Lithuanian Communist Party at the Palace of the Union of Soviet Artists of the Lithuanian SSR (14 b T. Kosciuškos St. in Vilnius; today, the Apostolic Nunciature at 28 T. Kosčiuškos St.). Among the exhibits was the painting ‘The First from the East’ by Vytautas Mackevičius, ‘A Portrait of Danutė Stanelienė’, a machine-gunner, by Irena Trečiokaitė-Žebenkienė, ‘The Progress of the Lithuanian Division at Oryol’ by Levas Mergašilskis, ‘A Portrait of Marytė Melnikaitė’ by Bronė Jacevičiūtė, the sculpture ‘The Stonemason’ by Bernardas Bučas, the composition ‘The Sheaf-Binder’ by Povilas Vitlybas, and the relief ‘New Settler’s Construction’ by Juozas Kėdainis.

Original is held at the Lithuanian Central State Archives

A return to Modernism

In the Soviet times, painting was considered the most prestigious art form, and its content and form were subject to detailed requirements. The modernization processes of the concept of Socialist Realism that started after Stalin’s death, in the period of political thaw at the turn of the 1950s–1960s, allowed departing from the strict academist-realist manner and encouraged the search for an individual style in art. True, this initiative did not come solely from the artists – the Soviet establishment also required new, more modern forms and a strong emotive effect. In many cases, we can see a return to expressive colourist painting predominant in the interwar period in Lithuania. The second room contains works attributed to this trend.

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

One of the greatest authorities for the young generation of artists was the professor of the Art Institute, painter Antanas Gudaitis. With his teaching and creative activity, he encouraged revisiting and newly interpreting interwar Modernism in response to the current reality. One of the founders of the interwar artists’ group Ars and, alongside, one of the founding fathers of the Lithuanian school of painting, in the late 1950s Gudaitis resumed painting in the expressionist manner and urged his students to choose this emotional trend. Thus, we could assert that he was an intermediary between the interwar school and the modernist endeavours of the young generation back in the second half of the 20th century. Gudaitis would often choose ideologically neutral subjects – the interior of his studio or a landscape. A motif of Old Vilnius (1958) is displayed in this exhibition.

Antanas Gudaitis (1904–1989)

Motif of Old Vilnius, 1958, oil on canvas, 92 × 77

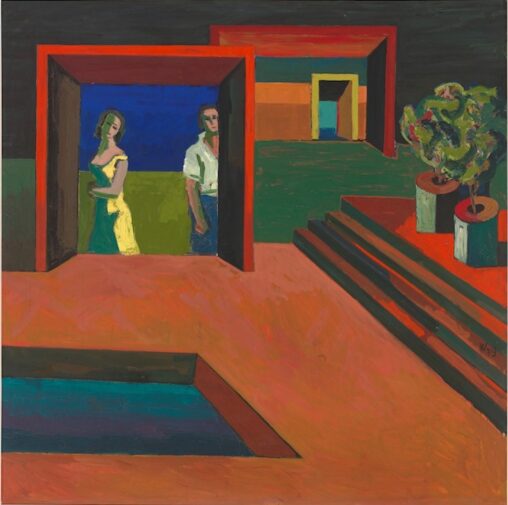

It was not only interwar art where the young generation was looking for inspiration – young artists were keen to get acquainted with the post-war tendencies of Western European art. The activity of Jonas Švažas was particularly important in consolidating new ideas in art. Between 1959 and 1969, this artist was the head of the Painting Department of the Artists’ Union.

Jonas Švažas (1925–1976)

A couple in the street, 1975, oil on canvas, 70 × 79

Changes were obvious not only in the form, but also in the contents of works. Socialist Realism was no longer strictly followed, a painting was no longer expected to present a simplified generally understandable visual narrative illustrating socialist welfare, and new plots and a more symbolical language appeared. Sometimes the plot seemed to lose its relevance and ideological colouring – for example, while depicting a couple of window-shoppers, Vincentas Gečas turns to the mundane daily life of a private individual. The painting is reminiscent of an amateur photograph still.

Vincentas Gečas (1931–2020)

Shop Window, 1960, oil on canvas, 92 × 120

MO Museum’s collection

Vincentas Gečas (1931–2020)

Portrait of Laima Cieškaitė, 1965, oil on carboard, 115 × 84

Silvestras Džiaukštas (g. 1928)

Night horse pasture, 1972, oil on cardboard, 122 × 100

Leopoldas Surgailis (1928–2016)

Penitent Magdalen, 1970, tempera on canvas, 130 × 97

Documentary footage ‘The Secrets of Beauty’, 1961. Unknown author, Radio and Television Committee at the Council of Ministers of the Lithuanian SSR.

Features on the artists Aloyzas Stasiulevičius and Augustinas Savickas.

Original is held at the Lithuanian Central State Archives.

Confrontation

The main hall contains paintings and sculptures from the late 1960s to the 1990s whose authors chose different strategies of making figurative art or abstractions as a means of confrontation with Socialist Realism.

Though both Vincas Kisarauskas and Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė studied under Antanas Gudaitis and admired his personality, they did not follow the Ars tradition in their work. Strict geometrization of forms became the key feature of one of the most radical modernizers of the 1960s art, Kisarauskas.

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

Vincas Kisarauskas (1934–1988)

Quiet Sunday, 1979, oil on canvas, 148 × 148

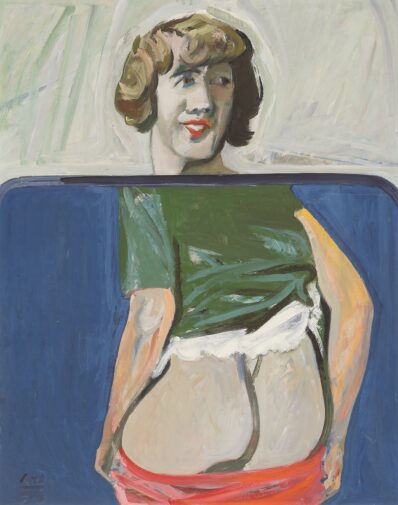

Having chosen the painter’s profession that was considered “unwomanly” at that time, in the 1960s Rožanskaitė was fascinated with the theme of scientific progress, technological innovations, and the relation of man and technology popular in that period (The Factory of Electronic Equipment, 1969). Since the 1970s, she had a lifelong interest in the theme of medicine and hospitals. Yet, her painting The Birth (1983) is not a typical “medical” work – puppets painted in a photorealist manner are not patients, but rather a dull crowd of extras, or a metaphor of the levelling of “Soviet citizens”. The shadow cast by a Soviet-style folding bed on which a baby is lying takes the shape of barbed wire. Most likely it is an allusion to her childhood experience, when Rožanskaitė with her mother were deported to Siberia. The artist kept returning to the deportation theme in her work

Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė (1933–2007)

The electrical equipment factory, 1969, oil on cardboard, 120 × 150

Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė (1933–2007)

The birth, 1983, oil on canvas, screen-printing, 150 × 170

View of the exposition

Deromanticizing painting was even more distinctly revealed in the work of Kostas Dereškevičius, Algimantas Kuras, and Arvydas Šaltenis of the 1970s. These artists programmatically sought to represent insignificant, daily objects and situations; “the faces and the bodies” of their paintings “were not beautiful, and their postures were neither graceful nor noble or magnificent”. Dereškevičius’s painting combines the most characteristic features of his work – image fragmentation, sarcastic composition of fragments, crammed spaces, bus windows – the painter’s favourite motif, – and the theme of the woman. Kuras took interest in insignificant, inaesthetic objects – for example, rusty pipes, which he painted close-up on the background of landscape.

View of the exposition

Kostas Dereškevičius (g. 1937)

Untitled, 1973–1974, oil on cardboard, 92 × 72

Algimantas Kuras (g. 1940)

Landscape with pipes, 1974, oil on cardboard, 57× 85

In his painting A Day in the City, Arvydas Šaltenis primarily captures a personal history. The central figure which is seen gesticulating in the crowd is Justinas Mikutis (1922–1988), a thinker and intellectual who became an icon of cultural resilience against the Soviet system. Šaltenis got acquainted with Mikutis, who had returned from deportation to Stalin’s gulags, in his youth and, having started to teach at the Art Institute, he invited him to work as a sitter. Mikutis eagerly kept company with artists and students, and to many of them he became an authority and a symbol of a free individual. In the painting created before Mikutis’s death, we can recognize the artist himself and the silhouettes of his wife Aldona and their son.

The writer Kristina Sabaliauskaitė called this painting an allegory of the late Soviet period: “We see a man with a clean-shaven head wearing a Soviet military uniform – it’s not clear if he’s a “demobee” or on leave – on the background of the sculptures of Green Bridge; there’s St Raphael’s Church on one side and Lietuva Hotel on the other; the bar on its 21st floor was teeming “intergirls” – Soviet hard-currency hookers, as was common knowledge among the residents of Vilnius. The faces of the sculptures, which today have already been dismantled, filled with Soviet-era determination, are vaguely painted and blurry; they have been reduced to dark spots and empty stocky bravura postures without contents. A real allegory of the late Soviet period. The “religious” past of Vilnius on the right, and the hard-currency international future on the left. The face in the foreground, to my understanding, is possibly a self-portrait. Yet, it is the alpha and omega of the entire picture. Because it’s the face of a live, suffering and doubting person having no lack of ruthless self-irony and realization of the existential absurd, wounded, vulnerable and, alongside, having an immortal soul. The face of Remark’s Roman soldier.” (Kristina Sabaliauskaitė, The Language of Words, the Language of Images: The Importance of Art and Literature in Today’s Changing World I, bernardinai.lt)

Arvydas Šaltenis (g. 1944)

A day in the city, 1987, oil on canvas, 140 × 120

View of the exposition

Figurative sculpture was characterized by the use of the principles of neo-classicism, generalized forms and symbolism, and the themes of motherhood and femininity. From the 1970s, the work of the sculptor Leonas Strioga featured an original type of a lyrical hero.

Stanislovas Kuzma (1947–2012)

Composition on the theme of woman, 1977, bronze, h – 28

Jadvyga Mozūraitė-Klemkienė (1923–2009)

Mother and child, 1988, terracotta, h – 19

Leonas Strioga (g. 1930)

Anūpras missing ploughed fields, 1990, wood, h – 33,5

One of the examples of the absurdity of the Soviet system was its intolerance of abstract art. It would seem that the Soviet authorities should have seen more threat in figurative compositions which could quite clearly or at least symbolically express the resentment at the present reality in their contents, but it was abstract art that was banned from official exhibitions up until the mid-1980s. It was seen as ideologically meaningless and failing to convey socialist contents. Another important aspect was the fact that this stylistics was related to Western culture or, putting it bluntly, was considered an attribute of “the rotten West”.

View of the exposition

The exhibition includes the collage Rosy (1982) by one of the first abstract artists in Lithuania, Kazė Zimblytė. Some viewers might find this work somewhat unusual due to the chosen media – canvas of crude texture or corrugated fibreboard. These media were quite customary in the West at that time, and it is obvious that the artist followed the tendencies of Western art. Certainly, her choice of materials might have been determined by another reason – restrictions for painting materials that were in force in that period.

Having finished textile studies, Zimblytė was not entitled to apply for these materials that were accessible only to the members of the Painting Department of the Artists’ Union. Thus, the artist would often work in the collage technique, using pieces of frayed textile, leather, foil, paper strips and other materials for her compositions, and was fond of spraying the surface of her works with nitroenamel paint or covering it with metallic powder of radiator paint.

Having chosen to create abstract art, which was considered harmful, empty, and apolitical, one of the first to work in this field in Lithuania, Zimblytė was not allowed to exhibit her works in official shows. However, like in the case of other artists who had fallen out with the Soviet regime, her works could be seen in more remote venues and were exhibited in private environments of like-minded friends and colleagues.

In an attempt to bypass the requirements of the Soviet establishment, an exhibition of Kazė Zimblytė’s abstractions was opened in the meeting hall of the Vilnius Vaga Publishers in 1968. The event attracted a huge interest from artists; not surprisingly, the organizers fell into disfavour with the authorities and two days later the exhibition was taken down. Vaga Publishers were instructed in the future to hold exhibitions only with permission from the Ministry of Culture of the time.

Kazė Zimblytė (1933–1999)

Rosy, 1982, collage, acrylic and bronze paint on canvas, cardboard and paper, 150,5 × 119

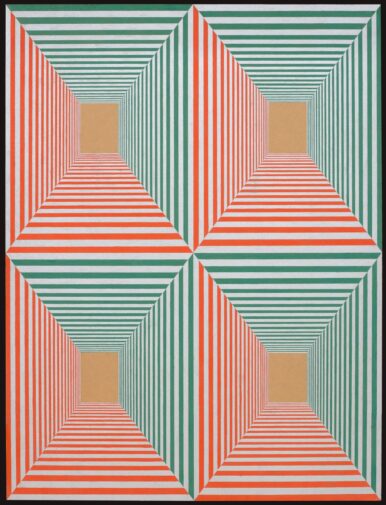

Vladislovas Žilius (1939–2012)

Op art composition, 1969, mixed media on cardboard, 86 × 65

Rimvidas Jankauskas–Kampas (1957–1993)

Abstraction, 1990, oil on canvas, 72 × 106

Mindaugas Navakas (g. 1952)

A sketch, ca. 1980, bronze, h – 18

Mindaugas Navakas (g. 1952)

Untitled, ca. 1977–1978, bronze, h – 22

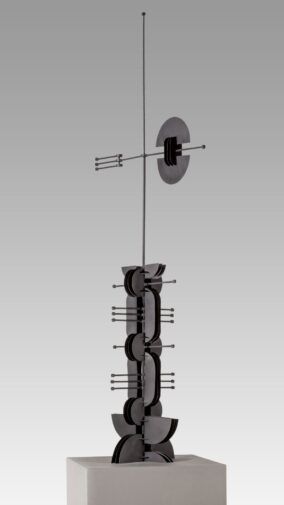

Teodoras Kazimieras Valaitis (1934–1974)

Weather vane, 1972, painted iron, h – 195

Creative individuality

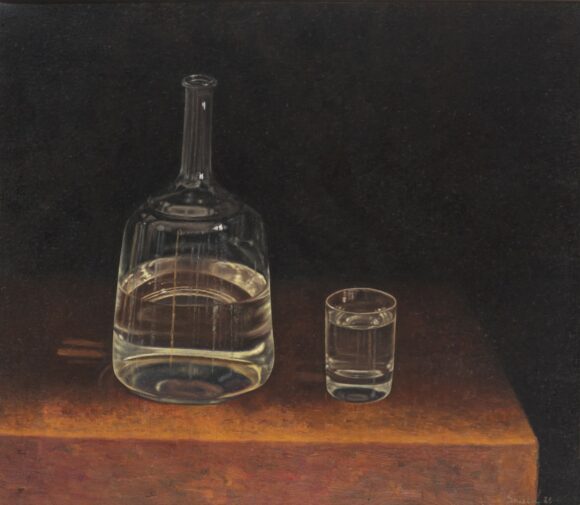

In this period, which was highly unfavourable for individual expression, some artists, such as Stasys Eidrigevičius, Šarūnas Sauka, and Raimundas Sližys, managed to preserve their creative individuality. Robertėlis in the country (1976) is an early work by Eidrigevičius, painted after a photograph taken by the artist (his graduation work was created according to the same principle). In 1980, Eidrigevičius moved to Poland and continued to work there. The early still-life A jug and a glass (1986) by one of the most renowned Lithuanian painters of the late 20th century, Šarūnas Sauka, illustrates the fascination with photorealism that became trendy in the USA and Europe in the 1960s–1970s.

View of the exposition

Stasys Eidrigevičius (g. 1949)

Robertėlis in the country, 1976, oil on canvas, 120 × 110

Šarūnas Sauka (g. 1958)

Decanter and glass, 1986, oil on canvas, 64 × 74

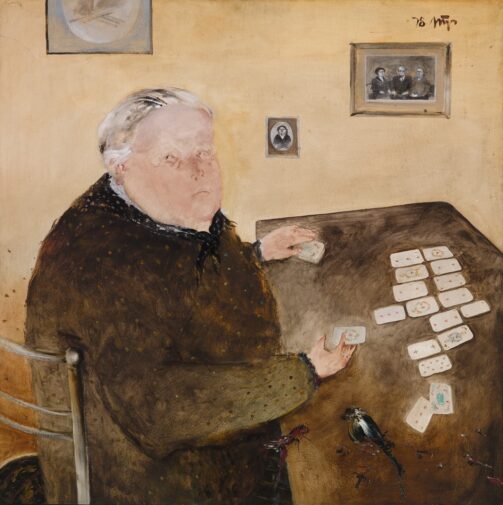

A sarcastic chronicler of bourgeois life, Raimundas Sližys, created an original and easily recognizable iconography in his paintings – his big-headed characters with small eyes and limbs are usually seen immersed in their routine rituals.

Raimundas Sližys (1952–2008)

Solitaire, 1978, oil on cardboard, 100 × 100

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

Lithuanian artists in exile I

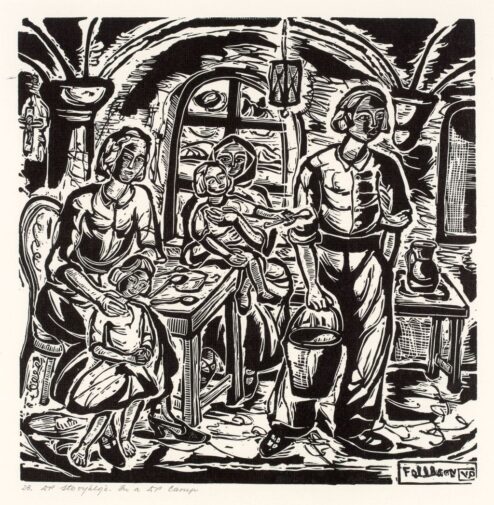

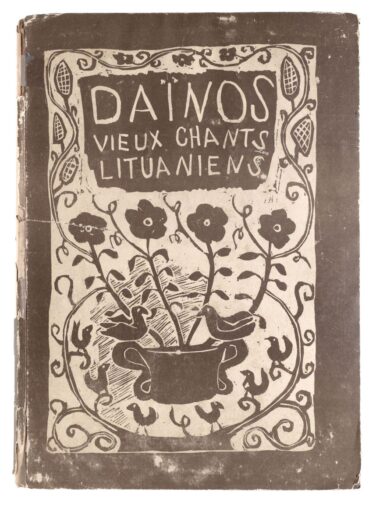

Approximately 60 to 70 thousand inhabitants of Lithuania fleeing from the approaching front and the second Soviet occupation were settled in displaced persons camps, mostly in West Germany and Austria. Among them were almost a hundred and fifty artists, who even in those difficult conditions soon resumed their creative activity: they founded private studios, decorated chapels and public buildings, held exhibitions, illustrated periodical publications, and published art books.

View of the exposition

Mykolas Paškevičius (1907–2003)

Untitled, 1947, oil on canvas, 46 × 65

Adolfas Vaičaitis (1915–2015)

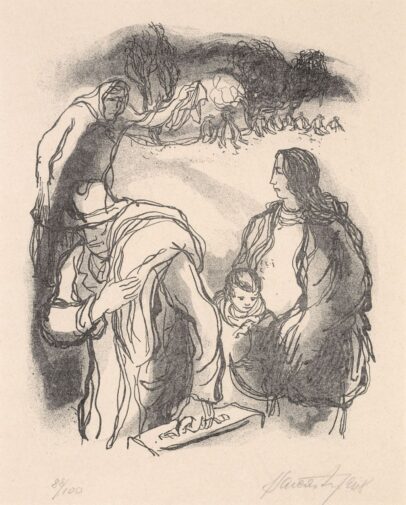

Farewell, 1948, lithograph on paper, 30 × 24

Viktoras Petravičius (1906–1989)

At a DP camp, 1949, linocut on paper, 48 × 38

Viktoras Petravičius (1906–1989)

Lithuanian Art Exhibition, 1948, colour printing on paper, 75 × 46

‘Lithuanian art in exile’,

München: T. J. Vizgirda, 1948

Gražina Krivickienė

‘Songs / Vieux chants lituaniens’, Breisgau Freiburg, 1948

Illustrations by Viktoras Petravičius

Salomėja Bačinskaitė [S. Nėris]

‘A Serpent’s Tale’, Memmingen: Lithuanian artists’ group Forma [1947]

Illustrations by Paulius Augius-Augustinavičius

‘Lithuanian marriage customs’, Göttingen, 1946

Illustrations by Alfonsas Dargis

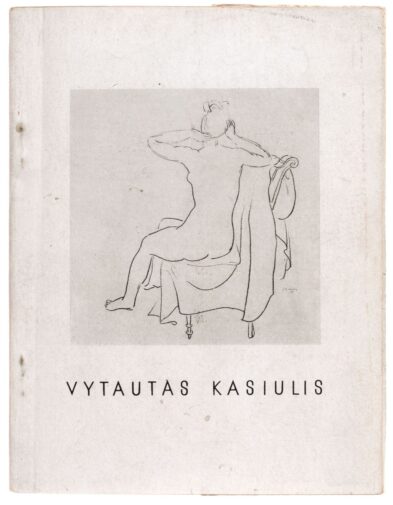

Aleksis Rannit, ‘Vytautas Kasiulis: Lithuanian painter’, Baden-Baden, 1947

The higher School of Arts and Crafts established in Freiburg in 1946 by the efforts of Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas became an extraordinary phenomenon. It offered an excellent possibility to present Lithuanian culture to the West and to continue the tradition of the Kaunas Art School. Alongside, it helped the members of the school’s community to make a living off their professional activity.

Teachers of the Freiburg School of Arts and Crafts were classics of Lithuanian art of the interwar period – Adomas Galdikas, Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas, Vytautas Kasiulis, Adolfas Valeška, and Viktoras Vizgirda. It was in that school that Vytautas Ignas, Antanas Mončys, Elena Urbaitytė-Urbaitis and others started to study art. The Freiburg School accepted not only Lithuanians, but also students of other nationalities.

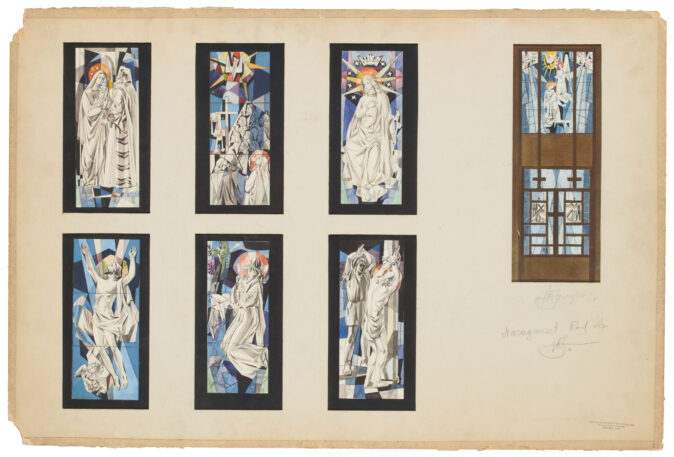

Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas (1907–1997)

Fifth Avenue, 1957, woodcut on paper, 31 × 36

Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas (1907–1997)

Cartoons for stained glass for the Christian Brothers Novitiate in Narragansett (Rhode Island, USA), 1959, watercolour, pencil, ink on canvas, 31 × 36

Vytautas Kasiulis (1918–1995)

The feast, 1940s, mixed media on cardboard, 42,5 × 55,5

Adolfas Valeška (1905–1994)

A Lithuanian girl, 1948, oil on canvas, 99,5 × 81

Viktoras Vizgirda (1904–1993)

A Boston cityscape, 1952, oil on cardboard, 56 × 72

Vytautas Ignas (1924–2009)

Madonna, 1970–1990, oil on canvas, 116,5 × 71,5

Antanas Mončys (1921–1993)

Owl, ca. 1955, bronze, h – 34

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

Lithuanian artists in exile II

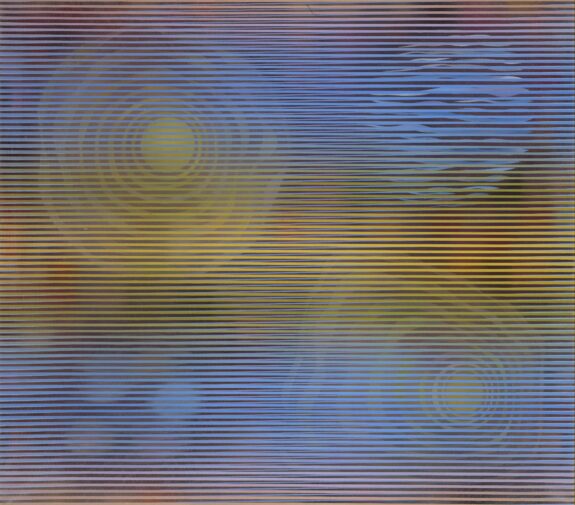

Though many artists who emigrated to the United States of America after the Second World War considered it important to preserve the features of national traditions in their work, some of them chose another path – to adjust themselves to the local art trends. At that time, abstract expressionism was the dominant movement in America, and thus, some of Lithuanian émigré artists chose to work in this style. Kazys Varnelis was one of the first Lithuanians to take interest in abstract painting in the early 1950s. Having tried his hand at abstract expressionism, geometric minimalism and other stylistic trends, Varnelis, just like Kazimieras Žoromskis, is best known for his op art compositions. Paradoxically, in 1986, Žoromskis returned to Lithuania, which was still under occupation, and Vladislovas Žilius who created op art incompatible with the Soviet official narrative and was unable to fulfil his creative ideas, chose emigration to the West.

View of the exposition

Kazimieras Žoromskis (1913–2004)

The Blue Rhapsody, 1975, oil on canvas, 138 × 160

Kazys Varnelis (1917–2010)

Innovation I, 1970, oil on canvas, 91,4 × 91,4

Having moved to New York in 1961, Elena Kepalas got acquainted with Jacques Lipchitz, who later wrote a foreword to the catalogue of her first solo exhibition in 1966. A reviewer of that exhibition, Žoromskis, noticed the influence of Lipchitz’s work on her sculptures.

Elena Urbaitytė-Urbaitis (1922–2006)

Composition, 1956, oil on canvas, 61 × 41

Albertas Vesčiūnas (1921–1976)

Impression of a landscape, 1950s–1960s, oil on canvas, 65,5 × 92

Elena Kepalas (1920–2006)

Untitled, 1950s, bronze, h – 28

The work by Pranas Gailius represents the French version of Abstract Expressionism. The sculptures by another Paris-based artist, Antanas Mončys, show a strong relation to Lithuanian folk art.

Pranas Gailius (1928–2015)

From the series ‘Adret (In the Sunshine)’, 1980s–1990s, acrylic on canvas, 43,5 × 54

Antanas Mončys (1921–1993)

Erotica, 1972, wood, h – 51,5

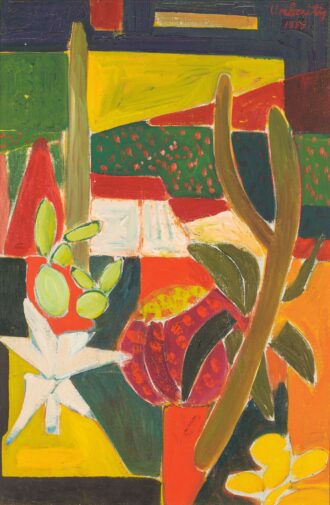

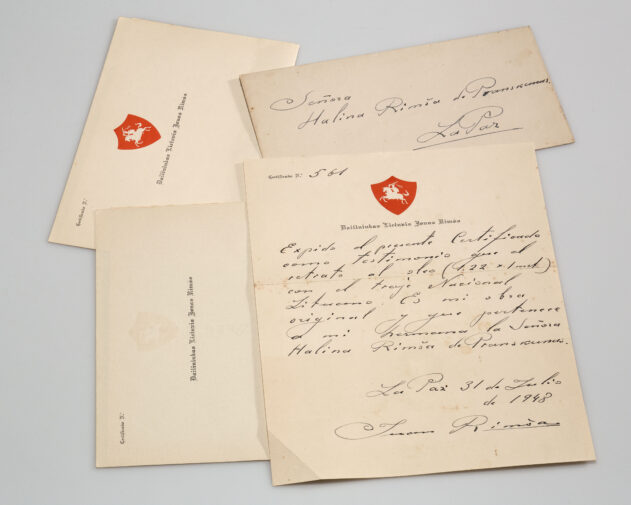

The work of Pranas Domšaitis and Jonas Rimša was not affected by the artistic tendencies that circulated in Lithuania. Domšaitis’s artistic individuality was formed in the environment of German Expressionism, while Rimša after his studies in Paris studied and worked in South America. Though he left Lithuania in the interwar period, he always stressed his Lithuanian origins. For example, his letterhead bore not only a printed Vytis symbol, but also the inscription “Lithuanian artist Jonas Rimša”.

Franz Domscheit (1880–1965)

Forest in Genadendal, 1961, oil on cardboard, 59 × 49,5

Jonas Rimša (1903–1978)

In a garden, ca. 1966, oil on canvas, 121 × 91

Correspondence of Jonas Rimša

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

Litvak art

The exhibition aims to bring out the specific character of Litvak works from the viewpoint of both content and form, and alongside, to emphasize that they are an integral part of the history of Lithuanian art, which was intentionally overlooked in the Soviet period.

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

Some of these artists fled from Lithuania or the Vilnius region which was part of Poland at that time due to economic or personal reasons already in the interwar period, while others emigrated in the years of World War II. The work of Lithuanian Jewish artists is distinguished by ethnic motifs of an extinct culture – shtetl life and personal tragedies related to the Holocaust.

Moshe Bernstein (1920–2006)

The Jewish boy, 1954, ink on paper, 70 × 44

Jeshua Kovarsky (1907–1967)

Still-life, 1960, oil on canvas, 100 × 80

Jose Gurvich (1927–1974)

Fisherman mending nets, 1951, oil on canvas, 45 × 34

Samuel Tepler (1918–1998)

Still-life with a model’s reflection in a mirror, 1980, oil on canvas, 35,5 × 50

Features associated with “Litvak melancholy” – nostalgia, intimacy, lyricism – are prominent. On the other hand, like Lithuanians, Litvak artists in emigration were keen on adopting the local art fashions.

Poster of the exhibition ‘Opéra de Quat’sous’ by Arbit Blatas, 1960

Galerie René Drouet, Paris, colour printing on paper, 70 × 50

Arbit Blatas (1908–1999)

Mother and child, ca. 1950, oil on canvas, 61 × 50

Arbit Blatas (1908–1999)

Lotte Lenya – Jenny Diver from ‘The Threepenny Opera’ by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht, second half of the 20th century, bronze, h – 36

Emmanuel Mané-Katz (1894–1962)

Flowers and a toy duckling, before 1962, oil on canvas, 55,5 × 46,5

Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973)

Reclining woman II, ca. 1950, bronze, h – 23

View of the exposition

View of the exposition