The second TARTLE exhibition – The Age of Romanticism

The collection of Lithuanian Art Centre TARTLE features numerous works of Lithuanian fine arts of the 19th century. The 2nd exhibition invites visitors to learn more about the 19th century through art history. This period is first and foremost linked to Romanticism, efforts to preserve historical memories, cherishing of traditions, accentuation of resistance as well as the cult of national heroes and spiritual leaders. On the other hand, romantic approach of the 19th century towards cultural life and artistic language conveys not only history, but also myths. Based on those aspects, the exposition seeks to disclose the spirit of the Romantic era as well as take a different look at what seems well-known.

The exhibition includes the works of painters, graphic artists and sculptors of Lithuania of the 19th century along with some works of foreign painters focused on the Lithuanian motifs. Visitors will find the works of less-known authors together with those of such celebrities as Franciszek Smuglewicz, Józef Oleszkiewicz, Edward Mateusz Römer, Albert Żamett, Michał Elwiro Andriolli, Kazimierz Alchimowicz, Wincenty Slendziński, Józef Bałzukiewicz, Mark Antokolsky and Ferdynand Ruszczyc.

The exhibition reflects various fields of fine arts of Romanticism; however, particular attention is given to graphic arts and book illustrations because these fields best demonstrate typical features of the age of Romanticism, such as inextricable link between art and literature, close cooperation of painters and graphic artists, dissemination of artistic works through the press and subscription, which resulted in fine arts becoming relatively ‘cheaper’ and more prevalent in various strata of society.

Specific features of the Romanticism worldview are revealed by employing certain themes. Thus the ground floor is dedicated to different aspects of Romanticism in art. History, fiction and fine arts of the 19th century turned their focus on Lithuania’s past. Interest in the past gave birth to a phenomenon which was especially characteristic to Lithuania in the 19th century – a passion for archaeology and accumulation of ancient monuments. The start of the exposition tells us about mythologization of history and aspiration to bring the heritage of the pagan Lithuania up-to-date, so typical of the Romanticism worldview. One of the spaces of the exhibition is designated to the typical painter of the 19th century of local origin and a description of his noblemen’s environment. Special attention is paid to Adam Mickiewicz, one of the brightest personalities of Lithuania’s and Poland’s culture in the 19th century; the plots of his works became an inexhaustible source for the fine arts of Romanticism.

Painters of Romanticism were looking for inspiring examples and heroic figures corresponding to the picture of a hero of the era. This is the focus of the story told in the rooms of the lower floor dedicated to heroes of resistance, such as legendary Tadeusz Kościuszko, a hero of Napoleon’s wars prince Józef Poniatowski, or peasants who defended Kražių church at the end of the 19th century. Another important source of inspiration for Romanticism painters was landscape. Landscape was understood as an important part of ethnic identity; it was believed to determine the character of people living in that land leading to the expression of the nation’s spirit. This topic is represented by paintings of Lithuanian artists, mostly landscapes, created abroad. The adjacent room houses paintings reflecting artists’ ambition to immortalize the originality of their homeland, convey its character as well as express its Catholic identity through religious plots and motifs. The Great Hall exhibits the most significant illustrated books of the 19th century, works created according to the motifs of literary works, authors’ portraits and illustrations of scientific works.

Rūta Janonienė

Art Historian, curator of the exhibition

Photo credits: Džoja Barysaitė, Antanas Lukšėnas

The digitization of the exhibition is partially funded by Vilnius City Municipality

find out more

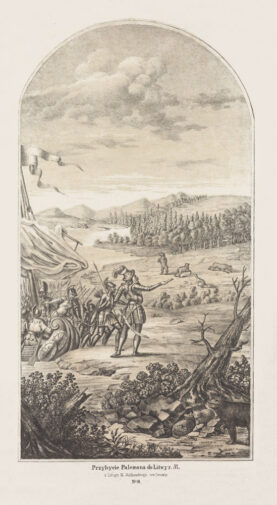

Mythological Lithuania

The study of literature and art in the 19th century looked to the past of Lithuania. Its old legends became popular, new legends started to emerge, and attempts were made to recreate the pagan mythology of Lithuania. The roots of present-day Neo-Paganism and the cult of pre-Christian Lithuania go back to the Romantic Era. The works in this part of the exhibition evoke well-known legends that were important to the Lithuanian identity, above all, the story of the Lithuanian nobles being descended from the Ancient Romans (the lithograph by Marcin Jabłoński).

Teofil Żychowicz, after Michał Stachowicz (1768–1825)

The arrival of Palemonas in Lithuania in the year 57 AD, 1852, lithograph, 68,2 × 52,9

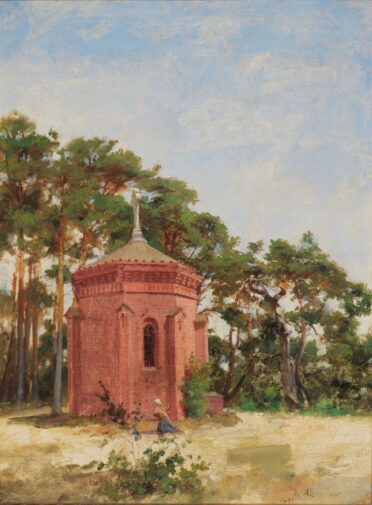

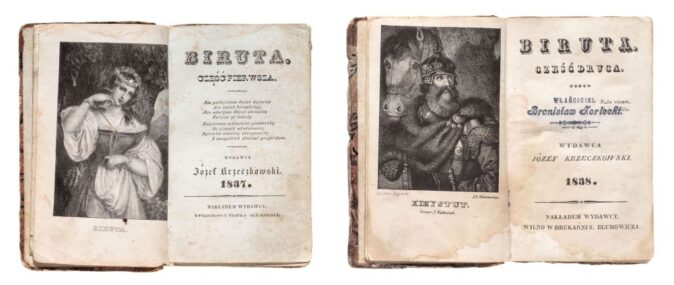

The growing interest in the 19th century in Lithuania’s past led to the emergence of works of literature and art about Duchess Birutė. No other female in pagan Lithuania has excited as much interest as the legendary guardian of the sacred flame. She lived at the junction of two epochs, and was the mother of Vytautas the Great, who laid the foundations for Christian Lithuania. This story is reflected in illustrations printed in the almanac Biruta, published in Vilnius in 1837 and 1838, and the painting by Kazimierz Alchimowicz.

Kazimierz Alchimowicz (1840–1916)

The chapel on Birutė Hill, 1899, oil on canvas, 41 × 31

Biruta, edited by Józef Krzeczkowski, volumes 1–2, Vilnius, 1837–1838

Illustrations by Antoni Pieńkowski

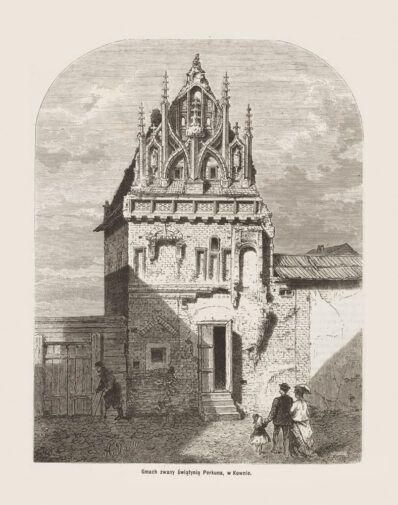

Józef Sosiński (?–1881), after Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1836–1893)

The building called the Perkūnas House in Kaunas, 1872, woodcut, 68,2 × 52,9

Hyppolite Moulin (1832–1884)

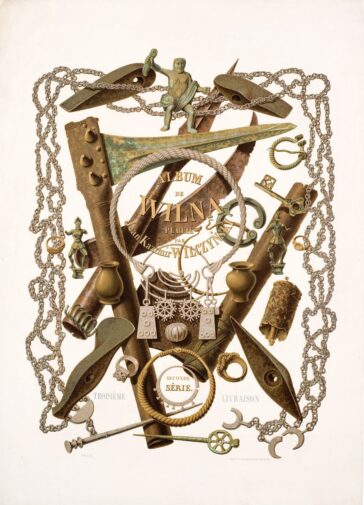

The title page of Jan Kazimierz Wilczyński‘s Album de Wilna (Album of Vilnius), series II, fascicle 3, No. 75, 1850

Chromolithograph, 55,5 × 40

The artist and his milieu

One of the first rooms in the exhibition is devoted to the artist and his milieu in the 19th century. Artists started receiving a regular professional training at that time, and a local intelligentsia emerged. This included a significant number of artists of local origin. Most 19th-century Lithuanian artists came from the nobility, from homes where a love for the homeland and notions of duty to society were encouraged, and hopes for freedom and a better future were cherished. This room includes a portrait by Michał Wichrowski, a little-known graduate of the Vilnius School of Art, which may be a self-portrait.

Michał Wichrowski (ca. 1780–?)

Portrait of a man, 1801, oil on canvas, 63,5 × 53,5

Unknown artist from the millieu of Jan Rustem

Portrait of a woman, before 1831, oil on canvas, 62,2 × 47,3

View of the exposition

The women’s portraits on display reflect a popular 19th-century genre, and a regular source of income for artists. The portraits reflect another important phenomenon: during their free time, artists would paint portraits of the people around them, portraits of relatives and friends, not as commissions but as presents. The typical living environment of an artist, whether it was in Vilnius or a house in the country, is illustrated by the view of a country house drawn by Michal Elwiro Andriolli, and the courtyard of the Römers’ house in Vilnius depicted by Edward Mateusz Römer. The artist’s painting of his horse also reflects his position as a member of the gentry.

Stanisław Bohusz-Siestrzeńcewicz (1869–1927)

Group portrait, 1906, watercolour and pencil on paper, 37 × 59

Stanisław Bohusz-Siestrzeńcewicz (1869–1927)

Portrait of Antonina Meysztowicza, after 1904, pastel and charcoal on paper, 44,5 × 44,5

Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1836–1893)

A manor house, 1881, pencil and ink on paper 16,5 × 25

Edward Mateusz Römer (1848–1900)

Winter landscape, late 19th century, oil on canvas, 33,3 × 41,7

Edward Mateusz Römer (1848–1900)

My Sorrel, late 19th century, oil on carboard, 28 × 35

View of the exposition

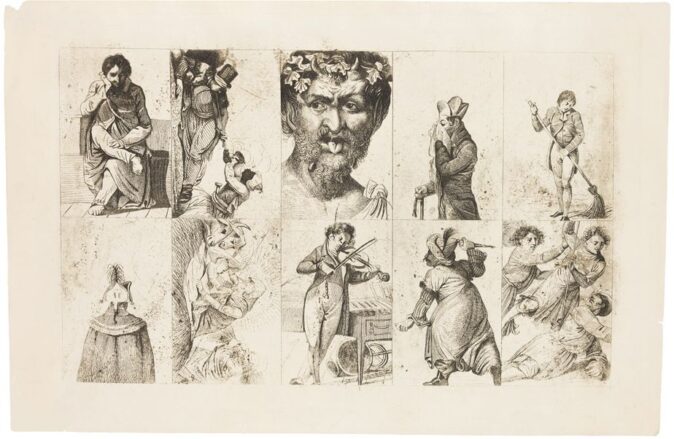

A sheet of cards created by Jan Rustem and Jan Gottlieb Kisling not only recalls this favourite 19th-century pastime among the nobility, but also some specific phenomena of the art of the period. It involved close cooperation between painters and graphic artists, the distribution of art through printing and subscriptions, the artists’ goal to expand the boundaries of art, and ways that new subjects and motifs entered into circulation.

Jan Gottlieb Kisling (1790–1846), after Jan Rustem (1762–1835)

Fantastic Cards, 1828–1831, etching on paper, 22,8 × 34,5

Adam Mickiewicz and art

Adam Mickiewicz was a prominent figure in 19th-century Lithuania and Poland. His reputation thrived despite the prohibitions at home and abroad, whereby the poet was forced to spend a large part of his life in exile. He was a major influence in shaping Vilnius’ brand of Romanticism.

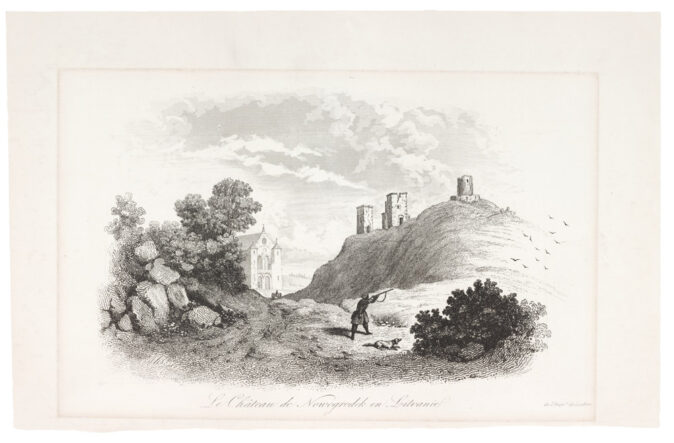

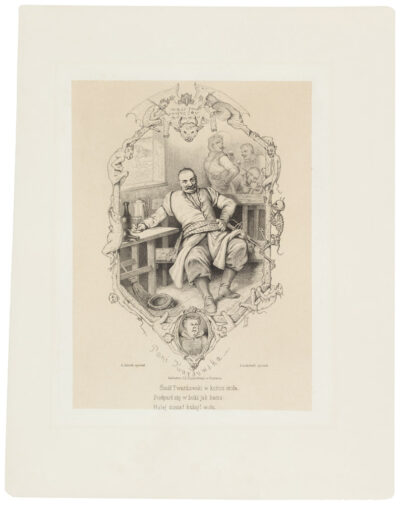

Throughout the 19th century, quite a few artists created illustrations for his books, or used subject matter from his work in their paintings. Images from his literary work, which exuded nostalgia for the past, replete with humour and irony, and occasionally fantasy and mysticism, were a steady inspiration for artists during the Romantic Era. Another aspect of his influence was not so obvious: his imagery, his character types, and the idealised atmosphere in a small manor house, were all reflected in work by many artists (such as Michal Elwiro Andriolli’s Is he coming?). Landscapes evoked the places where the great poet lived (Zaosye, Navahrudak, Kaunas), and portraits of the poet were also painted. In 1898, on the 100th anniversary of his birth, a monument was built to him surreptitiously in St Johns’ Church in Vilnius, in order to immortalise the memory of the celebrated citizen. In Warsaw and Cracow, the jubilee was celebrated more openly, and monuments were put up in public places. Events and publications were organised, and memorial medals were struck. A memorial plaque was cast in iron by the Polish company Znicz.

Besides the stories connected directly with the poet’s life and literary work, it is possible to talk about a different kind of influence he had on artists. The transformation of the protagonist Konrad (the poet) in his Forefathers’ Eve (Dziady), from a romantic towering over the crowd, and a rebel even challenging God, into a patriot who inwardly identifies with his fellow citizens struggling for freedom, had an influence on the understanding of the calling and the aims of the Romantic artist.

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1836–1893)

Is he coming?, 1876, watercolour, pencil, white pigment on paper, 55 × 39

Auguste-François Alès (1798–1878)

Navahrudak Castle, 1836, steel engraving, 17 × 26,5

Unknown artist

Adam Mickievicz’s plate, 1898, cast iron, 46 × 28,4

Stanislow Lukomski (1835–1867), after Antoni Zaleski (1824–1885)

Twardowski (illustration to Pani Twardowska by Adam Mickiewicz), 1863

Copper engraving, 27 × 21

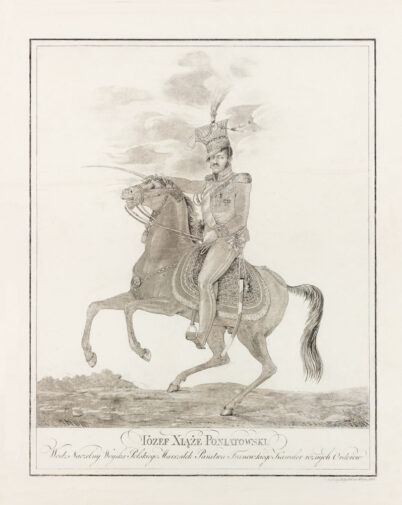

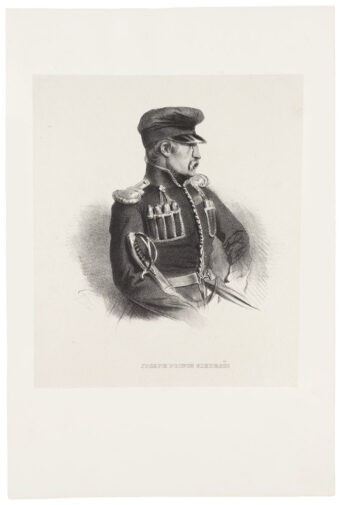

The Napoleonic Wars and the story of Józef Poniatowski

Artists in the Romantic Era looked for inspiring examples and heroic figures that would embody the image of the Romantic hero. Much attention was given to Count Józef Poniatowski (1763–1813), a symbol of the soldier’s honour and valour. He became a national hero in the first half of the 19th century, mainly thanks to his glorious involvement in the Napoleonic Wars and the struggle for freedom (he died at the Battle of Leipzig in 1813). On 10 October 1814, he was reburied in the Basilica of the Holy Cross in Warsaw. One of the illustrations decorating the ‘Historical Songs’ by Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz depicted this occasion. Even though the Russian authorities banned the songs from libraries, between 1816 and 1899 the book went through no fewer than 16 editions. In 1817, with permission from the Russian Emperor Alexander I, his remains were reburied next to royalty in the crypt of the Wawel Cathedral in Krakow. This must have been the occasion for Jan Gottlieb Kisling, a talented student in the Department of Graphic Art at the Vilnius School of Art, to create a solemn equestrian portrait of the hero to commemorate his glorious deeds.

Jan Gottltieb Kisling (1790–1846)

Prince Jozef Poniatowski, 1817, etching, aquatint, 54,5 × 42

M. A. Witek, after Swoboda

The funeral of Józef Poniatowski, 1846, lithograph 13,5 × 22,1

View of the exposition

Signs of Russian rule and the resistance to it

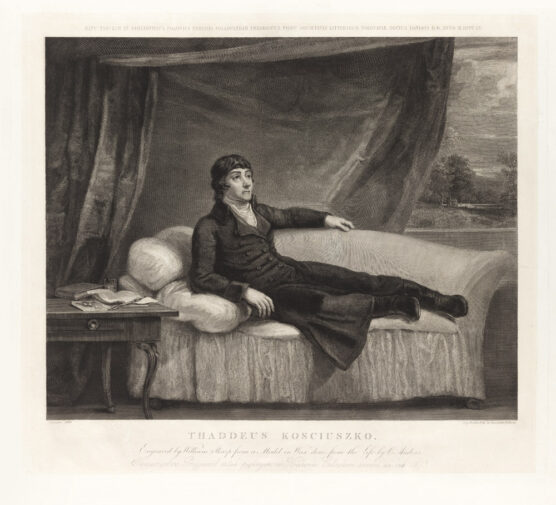

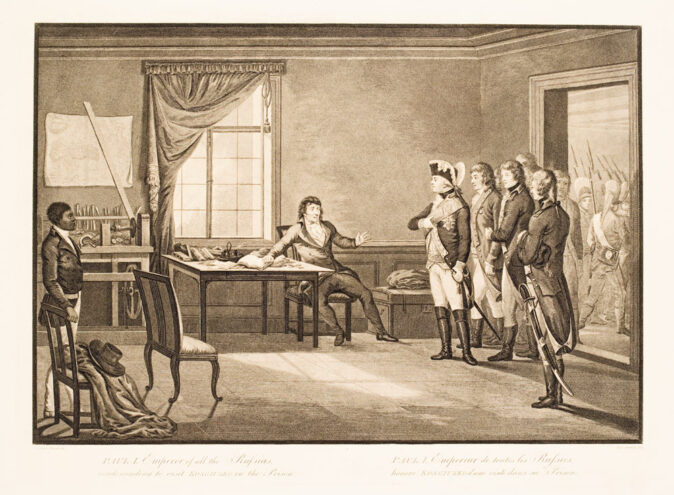

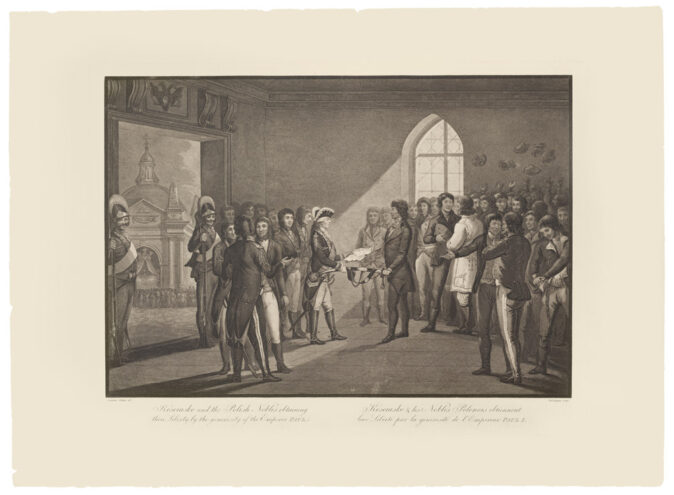

This part of the exhibition dwells on the theme of national resistance and the 19th-century struggles for freedom, from Tadeusz Kościuszko to the massacre at Kražiai. These events not only provided artists with subject matter; the fates of quite a few artists were connected with the anti-Russian liberation movement, being either directly involved in the armed struggle, or at least supporting the cause of freedom.

The resistance movement was in part responsible for directing the eyes of artists towards society’s third estate, the peasants. One of the earliest works in the style is Cracovians in a tavern by Franciszek Smuglewicz. After the first night of Jan Stefani’s opera The Supposed Miracle, or the Cracovians and the Highlanders (to a libretto by Wojciech Bogusławski) on 1 March 1794, Cracovians became a synonym for, and even a symbol of, a free, enterprising and patriotic nation. Tadeusz Kościuszko even tried wearing their white national costume, in order to emphasise his solidarity with the common people.

Franciszek Smuglewicz (1745–1807)

Cracovians in a tavern, ca. 1800, oil on canvas mounted on board 26,5 × 30

The figure of Tadeusz Kościuszko became another 19th-century hero and icon. The copious post-uprising iconography about Kościuszko evokes a moving and popular image of a defeated and suffering hero, although spiritually unvanquished.

William Sharp (1749–1824), engraving after a wax figure created by Katerina Andras (1775–1860)

Tadeusz Kościuszko, 1800/1855, paper, copper engraving, 46 × 50

Thomas Gaugain (1756–1812), after Alexander Orłowski (1777–1832)

The Emperor Paul I condescends to visit Tadeusz Kościuszko in prison, 1801, copper engraving, 43,5 × 58

Thomas Gaugain (1756–1812), after Alexander Orłowski (1777–1832)

Paul I releases Tadeusz Kościuszko from prison, 1801, copper engraving, 56 × 76

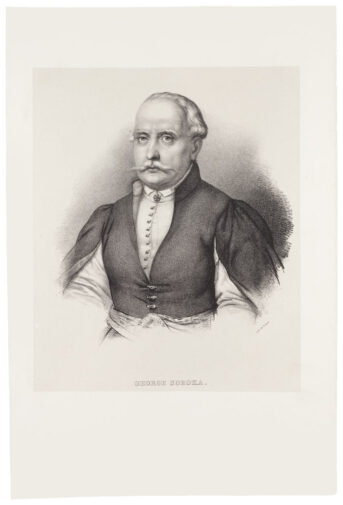

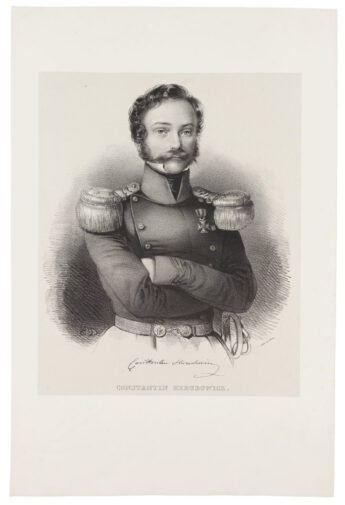

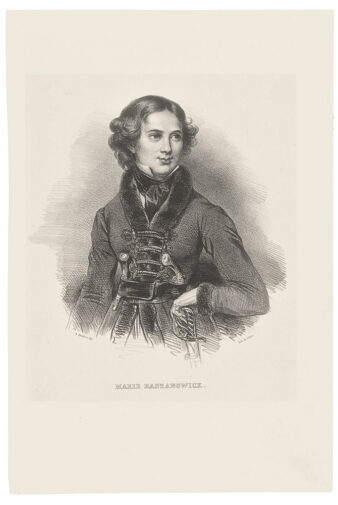

With the uprisings of 1830–1831 and 1863, people from different layers of society joined the liberation struggle. Many portraits of participants in the 1830–1831 uprising were printed in Paris in a publication compiled by Joseph Straszewicz, a Lithuanian nobleman, a former student at Vilnius University, a rebel, and a historian of emigration. His publication was entitled ‘Polish Men and Women in the Revolution of 29 November 1830’. The exhibition features the portfolio and eight individual lithographs.

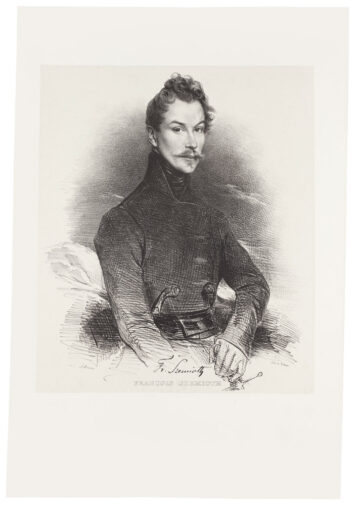

François Le Villain (1798–1884), after Antoine Maurin (1793–1860)

Ezechiel Staniewicz, 1832–1836, lithograph, 39,5 × 28,3

Unknown artist

Józef Giedrojć, 1832–1836, lithograph, 29 × 43,4

François Le Villain (1798–1884), after Józef Szymon Kurowski (1809–1851)

Jerzy Soroka, 1832–1836, lithograph, 43 × 28,2

François Le Villain (1798–1884), after Emile Demezon (1812–1880)

Konstanty Herubowicz, 1832–1836, lithograph, 28,6 × 23,4

François Le Villain (1798–1884), after Charles-Louis Bazin (1802–1859)

Michał Wollowicz and Leon Przecławski, 1832–1836, lithograph, 43 × 29,2

François Le Villain (1798–1884), after Achille Devéria (1800–1857)

Maria Raszanowicz, 1832–1836, lithograph, 43,5 × 29

François Le Villain (1798–1884), after Achille Devéria (1800–1857)

Franciszek Szemiot, 1832–1836, lithograph, 43 × 29,2

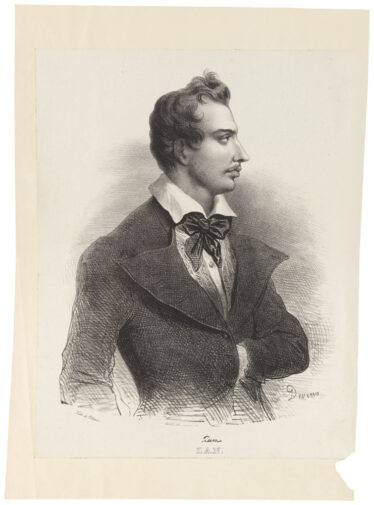

François Le Villain (1798–1884), after Achille Devéria (1800–1857)

Stefan Zan, lithograph,, 29,5 × 23,5

Unknown artist (Zygmunt Jakubowski?)

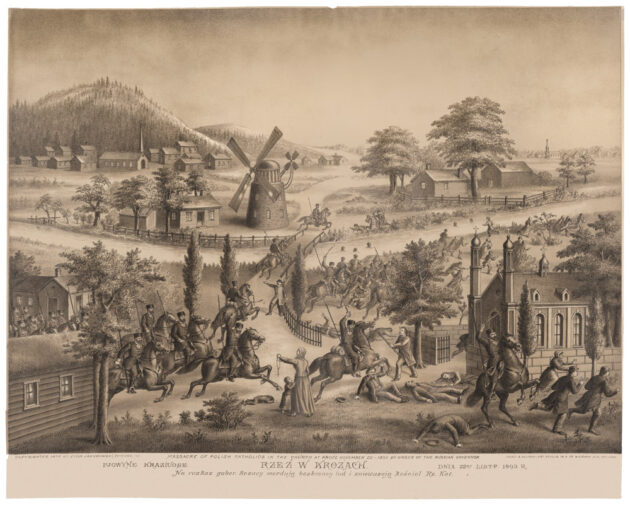

The Kražiai massacre, 1894, lithograph, 50, 6 × 63,5

The art studio Kurz & Allison was a major late-19th century publisher of chromolithographs based in Chicago. They established their reputation with images of the American Civil War published in the 1870s. In 1894, they produced a lithograph showing the Kražiai massacre in 1893 in a small town in Samogitia, news of which reverberated across the world. The events are said to have started with an imperial decree by Alexander II of 22 June 1893 to pull down the closed Benedictine monastery and Benedictine church in Kražiai. The community resisted the decision, and took turns to guard the church day and night, but on 21 November an order was issued to remove them. On 22 November, the police were joined by several hundred Don Cossacks, who broke the resistance of the believers by force. Nine people were killed in the attack, 50 were wounded, and dozens were arrested and put on trial. However, they succeeded in saving the church from being demolished.

The world was outraged by the Kražiai massacre and the policy of the Russian government towards Catholics. Thousands demonstrated in Western Europe and the United States, protests were sent to the emperor, and the press published articles condemning Russia. This lithograph was made in the context of these events. The artist tried to show the brutality and the cruelty of the Cossacks in attacking peaceful people. The situation of Kražiai and the church are imaginary. The lithograph was used as a prototype for a poster about the events in Kražiai published by Lithuanians in the United States, but the appearance of the church was changed in order to look more like the real structure.

Two paintings in this room are by Lithuanian artists who lived in St Petersburg for some time. A portrait of a Russian army officer by Jozef Oleszkiewicz, and Konstanty Benedykt Kukiewicz’s Asking for directions, which shows three cavalry officers in the times of Nicholas I, reflect indirectly Imperial Russian power and authority.

Józef Oleszkiewicz (1777–1830)

A cavalry officer in the Russian Imperial Guard, 1819, oil on copper, 66 × 57

Konstanty Benedykt Antoni Kukiewicz (1818–1840)

Asking for directions, 1837, oil on canvas, 30 × 36

View of the exposition

Local scenery and the Catholic identity

The loving gaze of artists in the Romantic Era was attracted by views of nature, and by local architectural and historical features. The landscape of the homeland was perceived by artists as part of the national identity, to the extent that they saw the national character as stemming from features of the natural surroundings. Architecture reawakened memories of important historical figures and events, and served as illustrations of history.

Images of castles evoked the country’s past grandeur, its rulers, and its independence (in this respect, the eloquent painting Castles of Vilnius by Juozapas Kamarauskas [Joseph Komarovsky] is of interest, based on watercolours by Franciszek Smuglewicz, recreating visually the demolished Lower Castle). Views of churches expressed the country’s Catholic identity, in a sense protecting Lithuanians from Orthodoxy, which was imposed from above. The same function was assigned to other religious works, which were not meant as altar paintings, but which showed people in prayer, or events from the history of religion (such as the apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Šiluva). Sometimes, Christ was depicted among common people and children, as if stressing his closeness to believers. Several paintings in this part of the exhibition from the end of the 19th century present this particular religious aspect of the Romantic sensibility.

View of the exposition

Tadeusz Dowgird (1852–1919)

A beggar by a shrine, 1888, oil on canvas, 42,5 × 55

Wincenty Leopold Slendziński (1837–1909)

At dawn, 1887, oil on canvas, 38 × 55

Wincenty Leopold Slendziński (1837–1909)

The fair in Vilnius by the Church of St Peter and St Paul, late 19th century, oil on canvas, 53,5 × 36,5

Unknown artist

The apparition of Our Lady of Šiluva, late 19th century, oil on canvas, 166 × 127

M. Bučinskis

Christ blesses the children, late 19th century, oil on canvas, 185 × 125

View of the exposition

Religious art in the 19th century went through a crisis. The role of the Church as a patron declined, due to the ban by the Russian authorities on constructing new churches, compounded by the difficult economic situation. However, artists looked for ways to create new and original religious works. The Bałzukiewicz family, who were closely involved with the Church of the Discovery of the Holy Cross in Vilnius, were especially active in this respect. They created several altar paintings for the church, and restored the paintings and sculptures in the chapels of the Stations of the Cross. Józef Bałzukiewicz’s St Dominic is a magnificent painting, simply in terms of its sheer quality. It is in keeping with traditional Dominican iconography, but the image of the saint has more immediacy than those that were created in the Baroque era: the saint looks like an ordinary person praying at an altar. The big open Bible is there to remind us of the great learning of the Dominicans, and it also points to the broader importance and influence of the written word. In the 19th century, the book was a symbol of cultural and religious identity.

Józef Bałzukiewicz (1866–1915)

St Dominic, 1898, oil on canvas, 173 × 143

Outside Lithuania

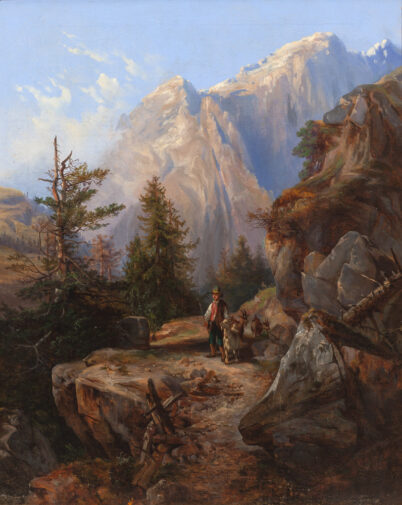

Artists in the Romantic Era often took an interest in different countries, their national characteristics, ethnography and landscapes. The landscape grew in importance in general, as views of local scenery were considered to be one of the most important elements of a country, and nature was perceived as a reflection of Divine Creation. Most Lithuanian artists in the 19th century lived abroad for some time, for they travelled to schools of higher education in Russia or in Western Europe. Others toured Europe, or they were forced into exile because of their political activities. This room includes works created by Lithuanian painters outside Lithuania, mostly landscapes. We can see many prints and book illustrations that were made in large quantities abroad in other rooms.

View of the exposition

Albert Żamett (1821–1876)

Italian landscape, 1861, oil on canvas, 77 × 105,5

Józef Marszewski (1827–1883)

Italian landscape, 1866, oil on canvas, 24,6 × 36,5

Ignacy Szczedrowski (1815–1870)

Flatlands, 1830s–1840s, oil on canvas, 41 × 54

Adolf Czapski (1819–1883)

Mountain landscape, 1830s–1840s, oil on canvas, 75,5 × 61,5

Several important sculptures, which are also products of the Romantic sensibility, broaden the display. These are Mephistopheles’ Head by Mark Antokolsky (he can be encountered in the writings of many Romantic writers, including Adam Mickiewicz, based on the most prominent appearance of this embodiment of evil in Goethe’s Faust), and the Gladiator by Pius Weloński, which was perceived by his contemporaries as an encouragement not to give up the struggle.

Mark Antokolsky (1843–1902)

Mephistopheles’ Head, 1879, bronze, h – 51,5

Pius Weloński (1849–1931)

Gladiator, 2nd half of the 19th, bronze, marble, h – 81

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

The Great Hall: art, literature and learning

The final part of the exhibition highlights an important aspect of art in the 19th century: its close links with literature. On the other hand, the works in this room also revisit the themes developed by works on display in the previous rooms.

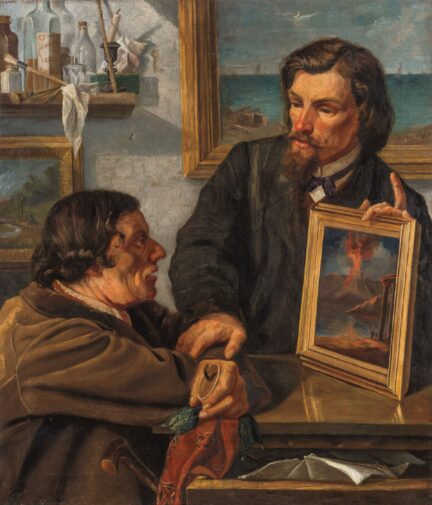

Roman Szwojnicki’s painting Provincial art is an ironic look at the subject of the artist’s vocation, and the role of art in educating society. He ridicules the provincial’s approach to art, and indirectly advocates support for local art that is not trivial, but which looks at topical problems in society and embodies social ideals.

View of the exposition

Roman Szwojnicki (1845–1915)

Provincial art, 1872, oil on canvas, 90 × 78

Leading literary figures took an interest in art and its role in society. The writer, publicist, historian and publisher Jozef Ignacy Kraszewski knew many artists, was an assiduous researcher of art history and a collector of art, and helped to shape the theory of Romanticism. He was also a talented draughtsman, painter and graphic artist: his painting Oriental portrait shows his artistic accomplishments.

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski (1812–1887)

Oriental portrait, 1846, oil on canvas, 82,5 × 65

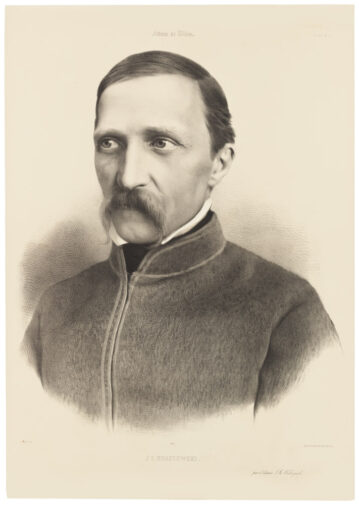

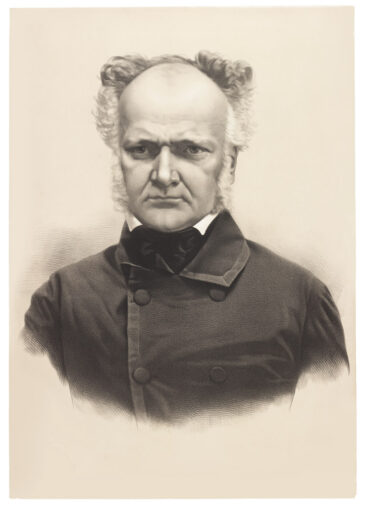

The exhibition features lithographic portraits of celebrated writers from the Romantic Era, including Kraszewski, Władysław Syrokomla and Eustachy Tyszkiewicz (a separate room is devoted to Adam Mickiewicz), as well as oil portraits thought to be of August Becu, a professor at Vilnius University, and his wife Salomea, the mother of the poet Juliusz Słowacki. Illustrations for scholarly and literary publications, which were an important part of Romantic art, are also on display. Books on botany, history and archaeology illustrated by artists helped to shape the Romantic sensibility. For example, the attention paid by botanists to the local flora encouraged artists to look more closely at the natural world. However, illustrations to literary works, of which many were made outside Lithuania, were of most importance.

View of the exposition

Adolphe Lafosse (ca. 1810–1879)

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski, 1851, lithograph, 51 × 37,9

Adolphe Lafosse (ca. 1810–1879)

The poet Władysław Syrokomla, mid-19th century, lithograph, 49 × 39

Adolphe Lafosse (ca. 1810–1879)

Eustachy Tyszkiewicz, 1856, lithograph, 57 × 40

View of the exposition

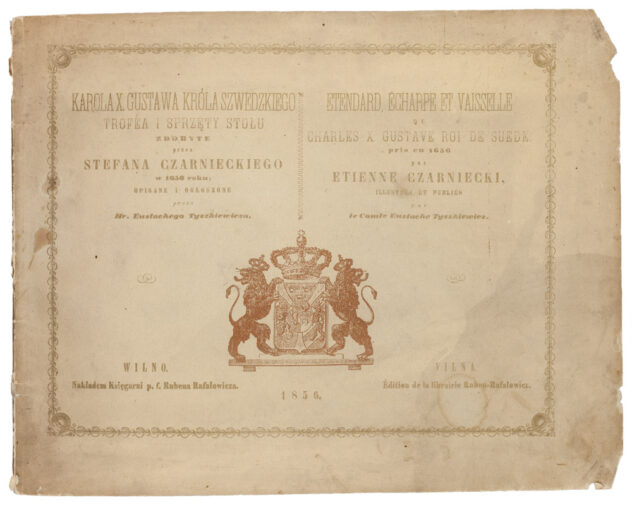

Eustachy Tyszkiewicz, Trophies and stationery of Charles X Gustav, King of Sweden, gained by Stefan Czarniecki in 1656, Vilnius, 1856

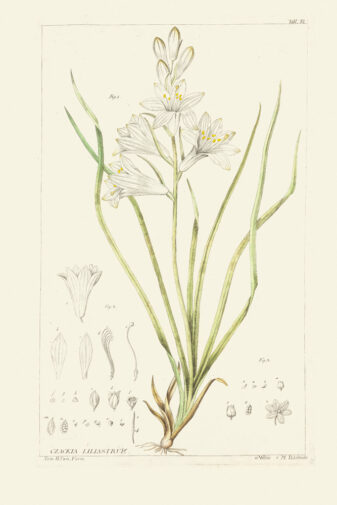

Michał Podoliński (1783–1856)

Czackia liliastrum, 1822, copper engraving, watercolour, 42,5 × 27,5

View of the exposition

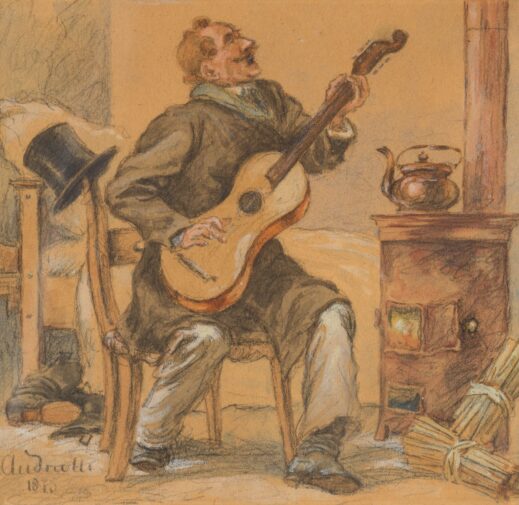

Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1836–1893)

Long live bachelorhood! (Wiwat kawalerski stan!), 1875, watercolour, pencil on paper, 20 × 22

Michał Elwiro Andriolli (1836–1893)

Illustration for Romeo and Juliet, 1855, watercolour, gouache, pencil and ink on paper, 36,5 × 29

View of the exposition

Another aspect of 19th-century art is its predilection for series of lithographs and illustrated books. Probably the best-known publication of this kind is the Album de Wilna (Album of Vilnius), which was brought out by Jan Kazimierz Wilczyński. The display includes individual lithographs from the famous publication. But more attention is paid to a different and lesser-known album, compiled by Eustachy Tyszkiewicz, entitled ‘Vilnius Museum of Antiquities’. It is a series devoted to a prominent cultural institution that collected historical and artistic artefacts. It also shows the broad concept of archaeology during the Romantic Era, when it embraced diverse areas of artistic creation.

Charles Claude Bachelier (mentioned in 1834–1852), after Albert Żamett (1821–1876)

A hall in Vilnius’ Museum of Antiquities, 1857–1858, Jan Kazimierz Wilczyński, ‘Album of Vilnius’, series I, fascicle IV

Chromolithograph, 55 × 66

View of the exposition

View of the exposition