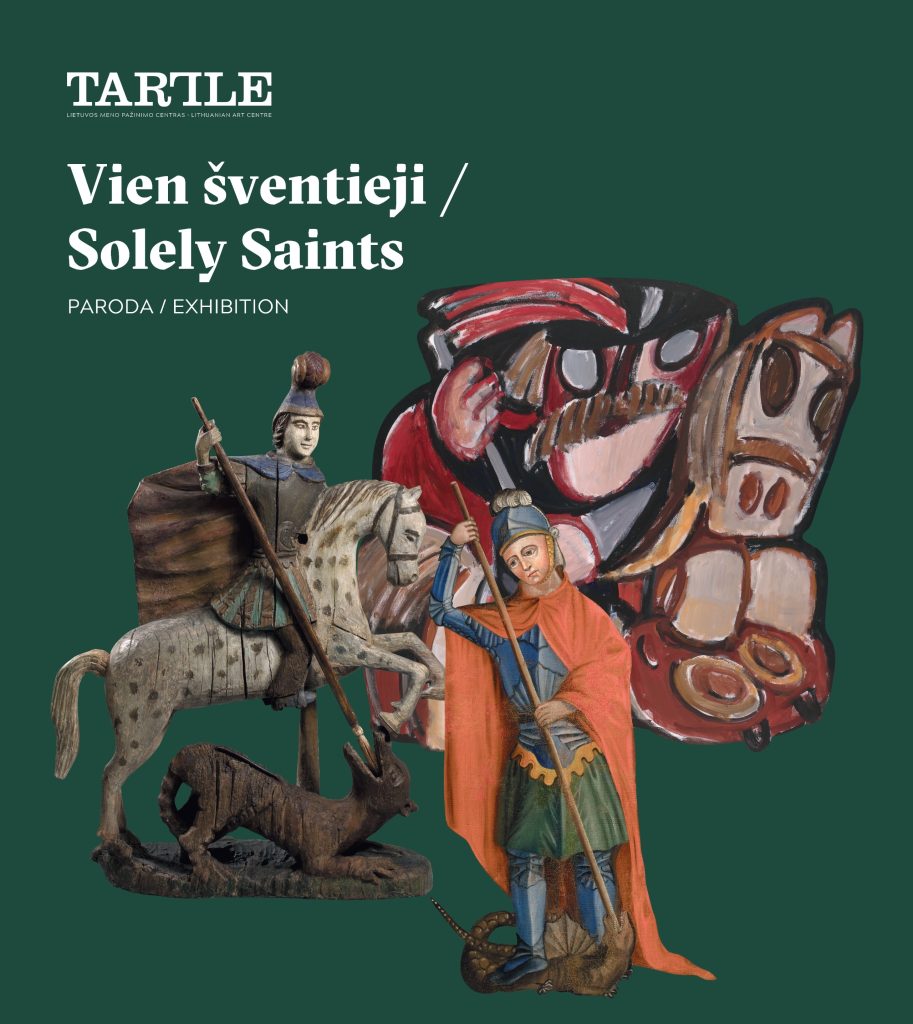

The seventh TARTLE exhibition – Solely Saints

In the TARTLE exhibition ‘Solely Saints’, we welcome you to explore depictions of saints spanning from the 16th century to contemporary times. Among them, you’ll encounter creations by artists who refined their craft over many years of practice, alongside works crafted by our forebears, self-taught village artisans who fashioned these figures in accordance with their faith and individual methods and means. Some pieces emanate from a quest for piety, strength, and hope, while others embody a vision of devotion crafted solely for its own sake.

In our exhibition halls, we invite you to explore the central iconographic themes of Lithuanian folk Christian art, from universal images portraying sorrow (such as Pieta, Christ in Distress, and Crucifixion), Christian love and hope (Our Lady of Mercy), the struggle against evil (St George), and themes of repentance (St Mary Magdalene), to local imagery integral to the religious and national identity of the Lithuanian people, including Our Lady of the Gates of Dawn, Our Lady of Šiluva, and St Casimir.

Since the era of national revival, numerous Lithuanian artists and cultural figures have shown a keen interest in folk art. They collected its examples, painted, and photographed them. In 1908, Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis remarked that Lithuanian folk art ‘is our pride due to its pure, distinctive, and exclusively Lithuanian beauty.’ This fascination with folk art, particularly expressed in the statuettes crafted by god-makers, known as ‘little gods’, persisted through the interwar years and the Soviet era. Quite many artists amassed collections, large or small, featuring these statuettes. Painters, graphic artists, and sculptors often drew inspiration from these collections, seeking ideas, motifs, and visual solutions in their iconography and forms.

Within the exhibition, folk art and professional works converge around thematic elements, offering a unique juxtaposition that illustrates how self-taught folk artists and trained professionals alike interpret the same iconographic themes. For instance, motifs from folk art have played a crucial role in the works of expatriate artists such as Vytautas Ignas, Antanas Mončys, Adomas Galdikas, and Pranas Domšaitis, helping them to underscore the essence of Lithuanian identity. During the Soviet era, artists like Albina Makūnaitė, Augustinas Savickas, and Leopoldas Surgailis created religious-themed pieces ‘for the drawer’ and never exhibited them publicly, as they not only reflected religious beliefs but also expressed a certain opposition to Soviet ideology. Conversely, contemporary artists like Kazimieras Brazdžiūnas, Viltė Čepulytė, Jonas Gasiūnas, and Emilis Benediktas Šeputis approach Christian symbols with multifaceted perspectives. They embrace the weight of symbolism accumulated over centuries while exploring opportunities to deconstruct, reinterpret, and desacralize these images in their canvases while offering experimentation through their chosen medium.

Comprising over 150 pieces, the exhibition draws from the extensive TARTLE collection as well as contributions from various private collections. Dr. Jaunius Gumbis, Ramutis Petniūnas, Skaidrė Urbonienė, Mindaugas Vanagas, auction house ‘Ars Via’, MO Museum, and ‘The Rooster Gallery’ have generously lent several exhibits. The exhibition aims not only to unveil these treasures from private collections but also to underscore the enduring affinity of artists for Christian imagery and the collectors’ inclination to cherish them as objects of devotion.

Curators

Dr. Skaidrė Urbonienė, Emilija Vanagaitė

Architect

Sigita Simona Paplauskaitė

Graphic designer

Daiva Sakalauskienė

Project is financed by Lithuanian Council for Culture

About the opening of the exhibition, exposition, and its exhibits:

Verslo žinios: https://www.vz.lt/laisvalaikis/pomegiai/2024/09/22/po-tartle-paroda–su-kuratore-e-vanagaite

Verslo žinios: https://www.vz.lt/laisvalaikis/pomegiai/2024/06/10/dar-vienas-tartle-kolekcijos-atsiverimas-vien-sventieji

read more

Unknown artist

Christ at the Pillar

Late 18th century – early 19th century

The Blessed Virgin Mary

The exhibition begins with depictions of one of the most significant subjects in Christian culture: the Blessed Virgin Mary. This theme in art is distinguished not only by its abundance but also by the prevalence of various iconographic types.

Among the most popular sculptures in folk art are those portraying Our Lady of Grace. This image is closely associated with the theme of the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Immaculate Conception. In both cases, Mary is depicted in a similar manner – standing barefoot on the globe, holding a snake and a crescent moon (or one of them), adorned in a white garment symbolizing chastity, and enveloped in a blue cloak symbolizing divinity. The distinction lies in the positioning of her hands: Mary of the Immaculate Conception is portrayed with her hands folded in prayer, while Our Lady of Grace is depicted with her hands lowered, radiating rays of grace. These rays serve as the focal point of Our Lady of Grace sculptures crafted by god-makers, commonly perceived as symbols of the graces bestowed by Mary and the fulfilment of prayers. Artisans often accentuated these rays, visualizing the essence of the image, by carving long, wide fan-shaped extensions, painting them in hues of yellow, gold, or silver – colours symbolizing love and heavenly light.

Juozapas Piaulokas (1860–1945)

Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception

Late 19th–early 20th century

At the turn of the 20th century, Juozapas Piaulokas, a wandering carver with no fixed place of abode, carved a number of sculptures on various subjects which can be found in the Plungė and Klaipėda districts. His sculptures were in great demand, and he was not short of orders to make crucifixes, shrines and figurines. Piaulokas’ works are distinguished by the meticulous representation of attributes, colour and other details, which help us to identify the saint. This sculpture of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception, although it has lost its colour, is easily identifiable from her posture, and from one of the main iconographic attributes, the serpent with an apple in its mouth, which in Christian art symbolises Satan and original sin.

Text author Skaidrė Urbonienė

Unknown artist

Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception

Late 19th–early 20th century

The veneration of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception flourished in the second half of the 17th century, but it became even more popular in the second half of the 19th century, after the dogma of the Immaculate Conception was proclaimed in 1854. The veneration of the Immaculate Conception in prayers and psalms became especially common in Lithuanian churches, and at home. Divine worship in the month of May became popular at the end of the 19th century, and the image of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception appeared in the liturgy. The custom of holding May services spread from churches to farms. Temporary altars with a picture or a sculpture of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception were placed in the home for the month of May. This stimulated the demand for images from carvers. The number of works grew in churches, and small pictures of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception spread all over the countryside. This influenced folk sculpture, which also took up the theme. Folk sculptures of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception deviate little from ecclesiastical iconography, craftsmen made various decorations for her head: a wreath of stars, a nimbus of rays, and sometimes a crown.

An unknown carver made this figure of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception in line with standard ecclesiastical iconography. Dressed in a white dress symbolising chastity, and a blue cloak symbolising heaven and divinity, she is standing on a globe, with her hands folded in prayer, and on a crescent and a serpent with an apple in its mouth. This kind of portrayal of Mary is not usually crowned; sometimes the head is covered with her blue cloak or a white veil, as in this work.

Text author Skaidrė Urbonienė

Blessed Virgin Mary with the Infant Jesus

In Lithuanian churches, depictions of the Blessed Virgin Mary with the Infant Jesus represent one of the earliest images of Mary. Moreover, a significant portion of the miraculous paintings that attracted crowds of pilgrims feature this motif. While various renditions of the Mother of God with the Infant Jesus exist in modern art, this theme is relatively scarce in Lithuanian folk sculpture. This image remains popular in art when depicting the general essence of womanhood and motherhood. Adjacent to the modern piece titled Madonna in the Street by Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas showcased in this hall, visitors can marvel at one of the oldest exhibits in the TARTLE collection: two delicately and sensitively painted pictures of the Mother of God with the Infant Jesus, dating back to the 16th century.

Unknown artist

The Virgin and Child

16th century

The picture The Virgin and Child has features of the Dutch Early Renaissance school. In the late 15th and early 16th centuries, intimate images were painted of the Virgin Mary and Jesus, expressing the sanctity of motherhood. This picture reflects exactly this interpretation: a delicate lady has a sorrowful look, and embraces the infant protectively and respectfully. He is standing firmly on his mother’s lap, with his face against her cheek, and his naked body is covered with translucent cloth. The glow of their halos is barely visible against the dark background. The picture was painted in the first half of the 16th century, and is a rather accurate copy of a famous work by Adriaen. Painted in about 1520, the picture was reproduced several times in the same century. Some of the copies are attributed to the artist himself. It is interesting that the composition of Isenbrandt’s picture might not have been original either. Twenty years earlier, the German painter Hans Holbein the Elder produced a similar Picture which is now in the Church of St James in Straubing in Bavaria. Its composition is identical to the picture painted by the artist from Bruges: the figures, the clothes, and even the pattern of the folds, are almost exactly the same. However, the pictures have a few important differences. In Holbein’s picture, Mary’s red garment is more sumptuous, and the texture of the fabric looks more natural. Holbein’s picture was also copied many times in the 16th century. During the lifetimes of these artists, copying works by renowned painters, and the replication of details, was a common artistic practice, free of the negative consequences of modern times.

Text author Dalia Vasiliūnienė

Views of the exposition

Pieta

In Lithuania, as early as the 15th century, depictions of the Pietà adorned churches and steadily multiplied in number. As Christianity took root among the peasantry, self-taught village artisans also began to create representations of this scene. Throughout the folk sculpture of the 19th to the first half of the 20th century, the Pietà emerged as one of the most prevalent themes among depictions of the Blessed Virgin Mary. Interpretations of this image abound in professional art as well.

The Pietà composition symbolizes not only the anguish of the Mother of God but also the collective sorrow experienced by mothers who have lost, mourned, or suffered the loss of their children. In folk sculpture, artisans accentuated the theme of pain and suffering by incorporating the symbol of a heart pierced by seven swords. Consequently, the heart is typically depicted as large, either carved in relief or presented as a separate detail. The seven swords piercing the heart are prominently displayed, symbolizing the seven sorrows of Mary as depicted in Christian iconography. The suffering of the Mother of God is further conveyed through the disproportionate depiction of the figures – often, the deceased Jesus is portrayed with diminished proportions, directing the viewer’s attention solely to the Mother of God. Moreover, to underscore her significance in the composition, artisans adorned Mary’s head with a prominent royal crown and encircled it with either a wreath of twelve stars or a nimbus of rays, and frequently, with all three elements.

Jurgis Balsevičius

Shrine with the Pietà

Late 19th century

Jurgis Balsevičius lived and worked in Vainutas in the second half of the 19th century and the early 20th century. He was a productive carver, whose works spread across Žemaitija. They could be found not only around Vainutas and in neighbouring villages, but in the more distant villages of Šilutė, Šilalė and Tauragė, and even around Plungė, Telšiai and Raseiniai. He liked to use tin in his work. He varied this image of the Pieta with a tin heart and seven rather large swords cut from tin.

Small shrines hanging in trees used to be found all over Lithuania. They were usually rectangular wooden boxes with a gable roof, open at the front, and sometimes glazed. Some of these shrines were decorated with openwork or shaped plates, sculptural decoration, miniature carved or turned architectural details, and paintings. Sometimes the roofs were topped with a small cross of wood or iron. Small shrines in trees with a sculpture of a saint were usually intended for private devotion.

Text author Skaidrė Urbonienė

Jonas Danauskas (1854-1937)

Pietà

Late 19th century

Jonas Danauskas became a skilled sculptor, and made accurate reproductions of religious art. One of his main activities was designing and making altars. His early sculptures are similar to folk art, but his later works are closer to those created by professionals.

This Pieta sculpture belongs to Danauskas’ early period: it is massive and frontal, and the folds of the drapery are divided into vertical strips. Although it is badly damaged, perhaps from being in an open roadside shrine for a long time, it has preserved the artist’s distinctive characteristics, with carefully carved, sorrowful, and at the same time lyrical and quiet, faces. The Pietas carved by Danauskas differ from those usually found in folk sculpture. He portrays Mary cradling Jesus on her lap or next to her, and there is little of the disproportion of the figures that is characteristic of sculptures by most religious carvers.

Text author Skaidrė Urbonienė

In church art, an extended version of the Pietà, known as the Lamentation (or the Lamentation of Christ) in iconography, is often portrayed. In this depiction, Mary is shown seated at the foot of the cross with the lifeless body of Christ laid across her lap, while saints such as John the Evangelist and Mary Magdalene, along with other holy figures, or just one or two of these figures, may be depicted alongside her. A painting exemplifying this scene is showcased in the exhibition.

The pain conveyed in the Pietà composition continues to resonate in modern art. For instance, Vytautas Kazimieras Jonynas depicts the scene of Christ being taken down from the cross against the backdrop of an industrial city, reflecting the enduring relevance of the theme to contemporary society. Meanwhile, Kazė Zimblytė offers abstracted and almost naïve interpretations of this scene. Sculptor Stanislovas Kuzma, on the other hand, opted for the image of the mourning Mother of God for the memorial honouring the defenders of Lithuania’s freedom in the Antakalnis cemetery in Vilnius. This choice resonates with people across generations, especially those whose relatives perished in wars and uprisings while defending their homeland from invaders. At the exhibition, visitors have the opportunity to view one of the initial wooden sketches of this monument dating back to 1992.

Stanislovas Kuzma (1947–2012)

Pietà

1992

Stanislovas Kuzma had no hesitation in choosing the classic composition of the Pieta for the Memorial to the Defenders of Lithuania’s Freedom. The image of the grieving Virgin Mary in the context of the ‘murderous events’ seemed just right to the artist. A small sculpture carved from wood in 1992 was one of the first versions of the monument. It has a pure, precisely modelled form, with very few realistic elements. The theme of the Pieta for a monument goes back a long way in the Christian world. Michelangelo’s Pieta, which is perhaps the best known, was commissioned in 1498 for the tomb of the French cardinal Jean de Bilheres in Rome. It looks as if the famous masterpiece might have influenced Kuzma’s choice of composition for his memorial.

Text author Dalia Vasiliūnienė

Views of the exposition

Jesus Christ

Daugelis savo namuose turi paveikslėlį, knygelę, nuotrauką ar suvenyrą su Jėzaus atvaizdu, o dairantis po įvairių kartų menininkų studijas galima pamatyti ir ne po vieną. Didžiojoje salėje pristatome svarbiausią krikščioniškojo meno temą – Jėzaus Kristaus atvaizdus. Parodoje eksponuojami tradicinėje liaudies dailėje populiariausi Nukryžiuotojo, Rūpintojėlio, Jėzaus Nazariečio, Jėzaus, nešančio kryžių, siužetai ir jų interpretacijos profesionaliajame mene. Tiesa, pastebima, kad šiuolaikinių menininkų kūriniai, vaizduojantys Jėzų, retai atranda vietą privačiose kolekcijose.

Crucified Christ

Cross-crafting monuments in all their forms, whether crosses, roofed pillar-type crosses, column shrines, or ground-standing shrines, typically featured a sculpture of the Crucified Christ, varying in size. It was customary for every believer to have a hanging or standing cross adorned with such a sculpture, sometimes even possessing multiple ones, in their homes. These crosses, known as “God’s suffering” or “home crosses,” held significant importance in family rituals such as birthdays, baptisms, weddings, and funerals, as well as during religious holidays. Revered and often passed down through generations, many of these crosses have endured to the present day. In this exhibition, we showcase a variety of home crosses, ranging from pieces embellished with carved details, tin embellishments, and expressive polychromy, to simpler ones devoid of elaborate decorations. Larger and more ornate crosses, featuring sculptures of the Crucified Christ, were typically displayed in churches, or carried during processions.

Also featured in the exhibition are standing crosses portraying an extended composition of the Crucifixion, where Mary (often depicted as Our Lady of Sorrows) and St. John the Evangelist are in most cases portrayed standing near the cross. At the foot of the cross, St. Mary Magdalene is typically depicted kneeling, often shown crying and either embracing the stem of the cross or the feet of Jesus. Both in professional art and folk sculpture, this composition exhibits several variations: sometimes only Mary and John stand by the cross, or only Mary Magdalene kneels. Less frequently, a lamb is depicted at the foot of the cross, symbolizing Atonement.

Juozapas Paulauskas (1860–1945)

Standing Crucifix with Our Lady of Sorrows, St John the Evangelist, St Mary Magdalene, two angels and Adam

First half of the 20th century

Small standing crucifixes, also known as ‘home crosses’, were often kept on a shelf above the krikštasuolė (baptismal bench). They were coloured artefacts, small, simple and often in one colour. The base was a plain quadrangular or rectangular plate or block. Geometric shapes were carved on the pedestals of the more decorative ones.

Juozapas Paulauskas, a religious carver from Grūšlaukė in the Kretinga district, carved several standing crosses with complex compositions. The base of the cross here is in the shape of a mountain rock (an allusion to Golgotha), and a sculpture of the body of Adam lies in a cavity below it. Our Lady of Sorrows and St John the Evangelist are standing on both sides of the cross, St Mary Magdalene is kneeling at its foot, and below her are two figurines of angels. The small cup for holy water between the angels is a characteristic feature of the standing crosses made by this carver.

Text author Skaidrė Urbonienė

Jesus of Nazareth

The popularity and widespread presence of the image of Jesus of Nazareth in Lithuania traces back to a statue famed for its miracles. Dispatched from Rome to the Trinitarian Church in Antakalnis, Vilnius, in 1700, this statue later found its home in the Church of St. Peter and Paul. By the second half of the 18th century, replicas of this sculpture began to be crafted for altars in Lithuanian churches, while carvings that gained prominence during this period served as models for provincial artists and god-makers, permeating rural landscapes and garnering popularity. In their monumental sculptures of Jesus of Nazareth, god-makers employed modest yet impactful techniques to convey the generalized image of the suffering and scorned Saviour, who was nonetheless resolved to bear the weight of humanity’s sins.

In this group of images, the only modern depiction of Jesus of Nazareth is the print Ecce Homo by graphic artist Albina Makūnaitė, created on the cusp of Lithuania’s state restoration in 1989. This artwork features a monumental figure of Jesus of Nazareth at its centre, flanked by details depicting the historical narrative of Lithuania on either side, interspersed with views of Vilnius. In this composition, the universal theme of the Saviour’s suffering intertwines with the artist’s personal reflections on the fate of the state and its people, the collective pain endured and the eventual triumph in the struggle for freedom.

Unknown artist

Jesus of Nazareth

Mid-19th century

Images of Jesus of Nazareth have a clear prototype in Lithuania. In 1700, a statue of Jesus of Nazareth was blessed by Pope Innocent XII in Rome and sent to the Trinitarian Church in Antakalnis in Vilnius (and later moved to the Church of St Peter and St Paul). It became famous for working miracles. Copies of the statue appeared in many churches in Lithuania, and served as examples for woodcarvers. Later, they began to make sculptures on the basis of the traditional imagery of the subject, instead of using actual models. In this sculpture by an unknown artist, Jesus is portrayed dressed in a long gown with his arms crossed across his chest. A rope around his neck and tying his wrists is carved in embossed relief; the loops are especially decoratively carved. The scapular usually worn by Trinitarian monks is a tetragonal plate with a cross painted on it.

Images of Jesus of Nazareth are evidence of the belief which prevailed in rural communities that Christ, who suffered such mockery and torment, was compassionate, and took pity on those who suffered, and that is why sculptures of Him were popular all over Lithuania.

Text author Skaidrė Urbonienė

Christ in Distress

Statuettes of Christ in Distress were commonly placed within small shrines nestled in trees along roadsides, in forests, and on homesteads. Often solitary in their setting, these statues symbolized an individual’s intimate connection with God and personal prayer in traditional culture. The pose of seated Christ in Distress, with his head supported by his hand – a gesture conveying both pain and contemplation in Christian iconography – fostered the perception of him as a suffering, compassionate Saviour. In the region of Žemaitija, local inhabitants referred to these sculptures standing at their homesteads as “The Provider” or “God’s Concern,” as they believed that they signified God’s looking after their families, dwellings, and farms.

Unknown artist

The Sorrowing Christ

Late 19th- early 20th century

An unknown religious carver made this sculpture of the Sorrowing Christ, one of the most popular images in folk sculpture, in the traditional way. The figure of Christ, crowned with a crown of thorns and wearing a dark-red cloak, is sitting with His head in His right hand and resting the other hand on the left knee. From the position of the left hand (the fingers are clenched, as if holding something), we can assume that He was holding a cane (a symbol of the Passion), a rather rare attribute in folk sculptures of the Sorrowing Christ.

In Christian iconography, the position of the Sorrowing Christ, with the head supported by the hand, signifies meditation and pain. This concept is particular to the national tradition of devotion. The Sorrowing Christ is seen by country people as the suffering and distressed Saviour. In this image, suffering is expressed not only by the posture, but also by the crown of thorns, which emphasises suffering, and also bloodstains. On the other hand, similar sculptures of Jesus placed in small shrines hanging from trees on farms in Žemaitija were often called the ‘Carer’ or ‘Provider’, as people believed that the Carer would look after their families and homes.

Text author Skaidrė Urbonienė

Adomas Galdikas (1893-1969)

The Prayer, 1920s

Toward the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, a fresh interpretation of the Christ in Distress image emerged, coinciding with Lithuania’s quest for national identity and its symbols amid the national liberation movement. Lithuanian intellectuals played a pivotal role in this transformation, linking the depiction of the anguished, sorrowful Christ with the collective sufferings endured by the Lithuanian nation. Thus, Christ in Distress came to symbolize the spirit and resilience of the nation. This symbolism was showcased when Lithuania presented itself at the Paris International Exposition in 1937. A monumental oak sculpture of Christ in Distress, portraying the historical plight of the Lithuanian nation, crafted according to the project of the sculptor Juozas Mikėnas, was exhibited there. Throughout the period of independent Lithuania and leading up to the Soviet occupation, Christ in Distress held sway as a symbol of the nation’s character, destiny, and history. This concept was further developed by diaspora artists, whose works emphasized the symbolic portrayal of Lithuania’s suffering and the imperative of preserving its national spirit, rather than a religious interpretation of Christ in Distress. In subsequent years, artists working during the years of Soviet rule and the National Revival period approached Christ in Distress as a source of solace, a symbol of defiance against the regime, and hope.

Jesus carrying the cross

In folk painting, the portrayal of Jesus carrying the cross typically finds its place among the Stations of the Cross series, depicting the arduous journey of Christ, battered, and scorned, bearing the crown of thorns, from Pilate’s courtyard to the crucifixion site at Golgotha. While paintings and graphic art often include additional figures such as Simon of Cyrene, who helped Jesus to carry the cross, and St. Veronica, who wiped his face with her veil, folk sculpture typically focuses on the solitary figure of Jesus. In traditional culture, this narrative resonates with the archetype of Jesus of Nazareth – the suffering Saviour bearing the burden of the cross (hardship), sacrificing himself to redeem humanity, and extending compassion to the downtrodden. Sculptures depicting this scene were commonly housed in brick shrines, some towering over a meter in height.

Eugenijus Varkulevičius-Varkalis (b. 1956)

St Veronica (Jesus Carries His Cross)

1983

Eugenijus Varkulevičius painted this picture of St Veronica when he lived in Žemaitija, inspired by the old Stations of the Cross that he saw in Beržoras. Made in the 19th century by unknown Žemaitijan artists, they used to be in the wooden chapels of the Stations of the Cross in the Beržoras Calvary. Although it was demolished in 1962 by order of the Soviet government, the parishioners saved the pictures. Charmed by the emotional expressiveness, the bold patterns, and the richly contrasting colours of folk painting, the artist created an unusual modern Expressionist version of the Passion.

Text author Dalia Vasiliūnienė

Views of the exposition

God-makers

As visitors admire the folk sculptures of saints, they may find themselves curious about the artisans behind these creations – who were they? How did they work? How did they live?

Known by various names such as dievdirbiai, dievadarbiai, dievmeistriai, or dievadrožiai (“god-makers,” “god-masters,” or “god-carvers”), these were amateur sculptors who carved statues of saints in villages. Often, these god-makers also crafted small-scale architectural monuments, such as crosses, column shrines, roofed pillar-type crosses, and shrines, into which their sculptures were placed. The majority of them hailed from humble backgrounds – poor, landless, or parcel-holding peasants, or town dwellers – for whom god-making served as a vital source of income or supplemented their earnings from the land. Some led nomadic lives, lacking a permanent residence, and traveling from one client to another. The majority were equipped with only rudimentary tools such as axes, chisels, planers, and knives.

Many god-makers began honing their craft in childhood, often moulding clay figurines or carving toys while shepherding. As they matured, they apprenticed under family members – often grandfathers, fathers, or other relatives – in carpentry or joinery. For those with a knack for artistic expression and sculpting, god-making would become their primary focus. Some artisans diversified their skills, mastering blacksmithing or painting, creating images, and Stations of the Cross for local parish churches. To showcase and sell their creations, god-makers would display them at home, take them to markets, or entrust them to traveling merchants during religious festivals. While some achieved fame as renowned masters of their craft and had many clients and buyers, others remained less known. The appeal of their works varied, from captivating primitive visual expressions to astonishing craftsmanship almost on par with professionals.

Artists Kazys Šimonis, Vytautas Bičiūnas, and Adomas Varnas, alongside regional ethnographer Balys Buračas and art historian Paulius Galaunė, admired the creative talents of village craftsmen, documented, and collected material about them. Thanks to their dedication, we have access to biographies and photographs of several god-makers who lived in the late 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, which were published in the press and preserved in manuscripts.

Views of the exposition

St George

St. George, a legendary Christian warrior, and martyr, holds a revered status throughout Europe. Legend has it that he was born into an aristocratic Christian family in Cappadocia, served in the Roman army, and rose to the esteemed military rank of tribune. In 303 AD, he was martyred for his commitment to spreading Christianity. St. George is revered as the patron saint of numerous countries, cities, knights, soldiers, and armourers, and is the second patron saint of Lithuania, following St. Casimir.

One of the most iconic depictions of St. George is his battle with the dragon, a scene widely portrayed in art. According to legend, during his travels in Libya, George learned of a fearsome dragon terrorizing the town of Silene, demanding the sacrifice of the townspeople’s sons and daughters. When the king’s daughter was chosen as the next victim and led to the dragon’s lair, George courageously intervened, riding on a white horse, and vanquished the dragon.

Juozapas Stankus (1840 – 1922)

St George

Late 19th century

St George is one of the most popular saints in Lithuania, and images of him are common in folk sculpture. Depictions of him are based on the story that on his way across Libya, he learned about a dragon that demanded that the citizens of Silene give it their sons and daughters to devour. When a princess was being taken to the dragon, George arrived on horseback and slew it. This image of St George was also popular in folk art. In this sculptural composition, the religious carver Juozapas Stankus depicted St George as a Roman soldier on a grey horse thrusting his lance into the dragon’s mouth. The figure of a praying princess is placed on a high postament next to the sculpture of St George.

The story about the slaying of the dragon is well known in many European and Asian countries, and signifies the victory of good over evil, which in Christianity became a symbol of its victory over paganism. But many nations in Europe, including the Lithuanians, celebrate the feast of St George (April 23) as the revival of nature in spring, and a date in the stockbreeding calendar, so St George is considered to be the patron of livestock, especially horses, and of farmers. In Lithuania, St George was also honoured as a patron of crops: people walked around their fields on St George’s Day, in order to ensure a good harvest.

Text author Skaidrė Urbonienė

In this hall, we invite you to marvel at the captivating compositions of St. George, renowned for their expressive and dynamic nature in folk sculpture. They are characterized by a harmonious blend of movement – such as the leap of the horse, the twisting form of the dragon, and the poised stance of the horseman with his spear – and static elements, notably the figure of the princess. Among the array of folk sculptures, compositions featuring St. George riding on horseback prevail, while occasional depictions of the saint standing are also found in church art and folk painting. Over time, as folk sculptures travelled from shrines to private homes and eventually to museum collections, many suffered damage or lost some details or composite parts. In the case of sculptures of St. George, the small figures of the princess often vanished from these compositions, leaving only a handful to be showcased in this exhibition.

Leopoldas Surgailis (1928 – 2016)

St George

1970s

The painter Leopoldas Surgailis’s inspiration from folk sculpture is obvious and even quite direct. Perhaps the most interesting case is the works from the cycle “Mythologies”, these works were even exhibited during the Soviet era – in 1966, in a personal exhibition held in Vilnius, which made the painter famous even in the Lithuanian community across the Atlantic Ocean. The exhibition “Solely Saints” exhibits two works from this cycle – “Penitent Magdalene” and “St. George”. The latter character, as art historian Laima Laučkaitė states, “provokes the question: does aggressive good, fighting evil, not become similar to or even more fierce than it?”

Text author Emilija Vanagaitė

In church art, the depiction of St. George underscores the triumph of the Christian faith: the valiant warrior vanquishes the dragon, symbolizing paganism. Meanwhile, in traditional Lithuanian culture, St. George conquering the dragon was revered as the protector of animals and crops, shielding them from malevolent spirits. This belief held sway in traditional culture until the mid-20th century, but a shift in interpretation became evident in later years, particularly during the period of national resurgence. During this time, the image of St. George battling the dragon took on new significance, symbolizing resistance against Soviet occupation.

Views of the exposition

Local Saints

Our Lady of Šiluva

Another significant image associated with Lithuania is the miraculous painting of Our Lady of Šiluva with the Infant Jesus, which also finds expression in folk sculpture. Devotional pictures featuring this image were widely circulated, serving as models for god-makers to carve sculptures. In this exhibition, a painting depicting the apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary in Šiluva in 1608 is showcased, itself based on a devotional picture. In folk sculpture, this particular image can be distinguished from other versions of the same subject by the specific postures of the Mother of God and the Infant Jesus: she holds the Infant on her left arm, with her right hand placed on the left. The Infant Jesus blesses with his right hand in the Latin gesture and holds a book in his left hand. Additionally, a star is depicted on the right shoulder of the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Unknown artist

The Apparition of Our Lady of Šiluva

Late 19th century

This picture portrays one of the most famous events in the history of the Church in Lithuania, the apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary at Šiluva in 1608. The Reformation had spread in Lithuania in the 16th century, and was still strong, and therefore the apparition at Šiluva was of great importance in the rivalry between the various confessions in the Diocese of Žemaitija. According to the story, which was written down in the 17th century, some young shepherds who were watching over their flocks in a field saw a girl on top of a large stone holding a baby in her arms and weeping. They sought out a member of the Calvinist Church to tell him about their vision, who repeated it to a Calvinist preacher. He went back to the field and saw the Virgin, and asked her why she was weeping. She answered that it was because people used to worship her son in that place, but ‘now they just plough and sow’, and then she disappeared. As dissenters, the Calvinists laughed at the vision, and interpreted it as the apparition of an evil spirit. But news of the shepherds’ vision quickly spread, and people recalled that there had once been a Catholic church on the site of the stone. Eventually, the place and the newly built church there became an important site of pilgrimage in the Diocese of Žemaitija,and the painting of the Blessed Virgin Mary that was placed on the main altar became famous far and wide for its powers of intercession. The picture was crowned in 1786, with the approval of the Holy See. This painting in the collection was based on a devotional picture printed in 1886 to mark the centenary of the coronation.

Text author Dalia Vasiliūnienė

Blessed Virgin Mary of the Gate of Dawn

The miraculous Vilnius image of the Blessed Virgin Mary of the Gate of Dawn, Mother of Mercy holds a prominent place in Lithuanian religious culture. Beginning in the mid-19th century, replicas of this revered image started to proliferate in churches, and by the century’s end, copies could be found in nearly every Lithuanian church. The widespread dissemination of prints, particularly those from Jan Kazimierz Wilczyński’s Vilnius Album, further popularized this image. As the cult of the Virgin Mary of the Gate of Dawn expanded, replicas of the image also began to emerge in folk art. God-makers endeavoured to faithfully replicate the original, although limitations in materials and techniques occasionally resulted in deviations from the prototype. Nonetheless, some folk sculptures quite closely resemble the miraculous image. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a period marked by national revival, replicas of the miraculous picture of Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn, along with images of St. Casimir, took on additional significance as symbols of freedom for the Catholic faith and the country. These images were often displayed together, reflecting both religious and national aspirations amidst the challenges of tsarist occupation. In the years of the Republic of Lithuania during the 1920s–1930s, the image of Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn acquired connotations of reclaiming the lost city of Vilnius. A poignant representation of this sentiment is captured in the 1937 poster created by artist Vaclovas Kosciuška.

Contemporary Lithuanian artists are increasingly drawn to religious images that hold significant sway in popular culture, including the revered image of Our Lady of the Gate of Dawn. However, rather than adhering strictly to traditional depictions, they often choose to desacralize the image and offer their own interpretations.

Juozapas Stankus (1840 – 1922)

Aušros Vartų Švč. Mergelė Marija

XIX a. pab.

Copies of the famous miracle-working picture Our Lady of Mercy of the Gates of Dawn in Vilnius can sometimes be found in Lithuanian folk sculpture. The cult of Our Lady of the Gates of Dawn began to spread in the second half of the 19th century, when copies of it carved by several religious carvers appeared in many Lithuanian churches.

Juozapas Stankus, a carver who lived in the village of Pazimkalnis in the Tauragė district, carved a close copy of Our Lady of the Gates of Dawn: a frontal image, with the head inclined to the right, and the hands crossed on the bosom. He carved only the upper half of the figure, just as she is portrayed in the famous picture. Mary is crowned, and the crown is topped with another crown, as in the picture. But the angels supporting the second crown are placed lower in the sculpture than they are in the picture. Each one formerly held a candle, probably to focus on Mary’s suffering. The carver adorned her cloak with lightly carved floral motifs, in imitation of the casing of the miracle-working picture.

Text author Skaidrė Urbonienė

St Casimir

The iconography of St. Casimir (1458–1484), the Prince of Lithuania and Poland, and the heavenly patron of Lithuania, who was canonized in 1602, began to take shape in the 17th century. During this period, he came to be depicted with a lily and a cross. In the 18th century, additional elements were incorporated into his depictions, including the figure of Cupid, a self-flagellation tool, and crowns lying at his feet, among other symbols. In folk sculpture, the iconographic tradition established in the 17th century has been predominantly preserved: St. Casimir is typically portrayed standing, adorned in a royal mantle lined with ermine fur, a crown atop his head, and holding a crucifix and a blossoming lily branch in his hands.

In the early 20th century, the cult of St. Casimir began to acquire distinctive characteristics. During this period, Catholicism became intertwined with Lithuania’s national identity, leading to the association of the saint’s name with Lithuanian culture, national self-awareness, and youth education. St. Casimir’s patronage in resisting oppressors was particularly emphasized. Alongside works from the 19th and first half of the 20th century, the exhibition also features a piece created in the 21st century, reflecting a practice observed in Renaissance art, where painters would depict themselves as saints. In this instance, the painter Kazimieras Brazdžiūnas presents a self-portrait through the image of St. Casimir, the patron saint of Lithuania.

Antoni Oleszczyński (1794-1879)

St Casimir

Mid-19th century

St. Casimir is the heavenly patron of Lithuania, the prince of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and Poland. He is a historically existing person. In our collective consciousness, a very clear and individualized image of him has been formed – a young man with long wavy brown hair, dressed in a sable fur coat, often with a crown on his head, holding a white lily in his hand. Looking at the image created by Antonio Oleszczynski in the middle of the 19th century – we really see a prince who is not our own. This image of St. Casimir is a copy of the image of another saint already existing – st. Louis. The actual similarity between them is quite direct – both of them are saints from royal families. Charles Lebrun, the painter of the royal court of the Sun King – Louis XIV, created such a praying St. in the 17th century. The image of Louis, a copy of which later adorned the Trinitarian Church in Lutsk, and before us today, only with the name of St. Casimir, a copy transferred in Oleszczynski’s engraving, allows us to believe in a falsified image of our holy prince.

Text author Emilija Vanagaitė

Views of the exposition

St Mary Magdalene

St. Mary Magdalene, a devoted follower and helper of Jesus Christ, is a frequent subject in church art. The image of the repentant sinner, which emerged during the Middle Ages, continues to inspire artists’ creativity to this day. The saint is often depicted with long, loose, flowing hair and accompanied by a skull – a symbol of penitence, – and her clothing, depicted as sliding off her body, symbolizes her liberation from earthly desires. Take, for instance, Leopoldas Surgailis’s Repentant Magdalene from the Soviet era, identifiable by the abstracted skull in the corner. While conventionally, the focus lies on portraying the penitent’s beauty, this rendition presents Magdalene in a somewhat grotesque manner, with a pronounced chin reminiscent of the sculptures crafted by the god-makers of Žemaitija.

Unknown artist (Kanuty Rusiecki? (1800–1860)

St Mary Magdalene

Mid-19th century

St Mary Magdalene was often pictured in Baroque religious art. The Counter Reformation took up the story of the repentant sinner in order to emphasise the importance of confession and the Sacrament of Penance. St Mary Magdalene, who accompanied Christ in the earthly life together with the Apostles, was often portrayed below the cross in the Crucifixion, or beside Christ’s tomb, as an important witness to the Resurrection, or as a lonely penitent deep in prayer in a deserted grotto.

This is an exact copy of a picture painted around 1633 by the famous Bolognese artist Guido Reni. The copy is meticulously made, with even small details and the authentic dull colouring reproduced. The top of the canvas has been cut off, and only half of the angel flying over the cross and part of another one are left. It is clear that the copy was made by a very skilled painter, who was familiar with the principles of European Classical art. The painter could have been Kanuty Rusiecki, who lived in Italy for ten years, studied art, and copied works by Italian artists.

Text author Dalia Vasiliūnienė

Unknown artist

St Mary Magdalene

17th century

This primitive sculpture was made by an unskilled carver, and is therefore difficult to date. However, it differs from the folk art of the 19th century in several small features and rare details. The motionless and narrow-shouldered figure of St Mary Magdalene has discreet silhouettes and minimal modelling, and is standing with the right hand pressed to her bosom. An effort was made to make the clothing of St Mary Magdalene more ornate: the dress shrouding her figure has a Gothic silhouette, and the long hair falling down her back is notched in imitation of a hairnet. The sculpture was probably part of a larger composition portraying the Crucifixion.

Text author Dalia Vasiliūnienė

In folk art, finding an autonomous portrayal of St. Mary Magdalene is exceptionally rare compared to professional art. Perhaps the sole example is a sculpture portraying the saint kneeling in prayer at a table, on display in this exhibition. The depiction of this saint is commonly integrated into folk sculptural compositions of the Crucifixion, which are showcased in the hall dedicated to the theme of Jesus.

Views of the exposition