The first TARTLE exhibition – A Glance at the History of Lithuanian Art from Užupis

The gallery of the Tartle Lithuanian Art Centre is a new centre of attraction on the Vilnius cultural scene, situated at the highest point in Užupis, near the square at which Užupio Street divides into Krivių and Polocko streets. The first Tartle exhibition offers a view from the hill, looking to the north, west and south, to explore the peaks of Lithuanian art history.

The three halls on the ground floor, and the five halls on the lower floor, feature works of art from the late 18th to the early 21st century, which specialists have attributed to the treasury of Lithuanian art: 46 paintings, 13 sculptures, and two engravings. They introduce the huge Tartle collection, with more than 7,000 exhibits. The exhibition reveals three aspects: 1) the Lithuanian character of the collection and its orientation towards modernism and the classics; 2) the educational opportunities offered by the collection, which are enhanced by the gallery’s location in a historic part of Vilnius; 3) the effect that private collections have on boosting the value of the national cultural heritage, expanding our knowledge, and developing the ability to perceive criteria in assessing the cultural heritage.

The ground floor of the gallery joins reality with its artistically transformed image. In other words, in the three halls of the ground floor, visitors are offered a view of the surroundings of Vilnius through the eyes of 20th-century artists, to show what has changed, what is no longer there, and what has stayed almost the same as it was 50 or 100 years ago.

The exhibition on the lower floor emphasises the most important stages, ideas and their artistic incarnation, in the development of Lithuanian art. It is about trends, schools, famous names, and works that have become part of the national cultural canon. This part of the exhibition combines segments illustrating different creative strategies: the expression of colour and gesture painting, meditative art, and rational analysis.

The visitor can follow the development of the exhibition through themes. The beginning of the historic heritage of Lithuanian art is presented by Franciszek Smuglewicz’s masterpiece Esther before Ahasuerus, visible through the glass of a repository. The aim is to emphasise the fact that this painting, which is itself of exceptional value, represents a larger whole: art treasures accumulated in a particular storage, and what we have preserved or brought back to Lithuania. The beginning of the story of the national art is marked by paintings by famous artists such as Petras Kalpokas, Kazimierz Stabrowski and Antanas Žmuidzinavičius exhibited in the two smallest halls. The variety and dynamics of the growing area of art in the 20th century is shown by the number of artists who worked in Lithuania and abroad, illustrating a different relationship with the creative process and its results. This variety is summed up by three categories or concepts: contemplation, passion and synthesis. The latter is shown through the concentrated narrative in the Great Hall, which allows us to see and appreciate the diversity of Lithuanian art in the 20th century, what different forms developed, what the prevailing local tendencies were, and to what extent and how they were influenced by major Western cultures.

Giedrė Jankevičiūtė

Art historian, curator of the inaugural exhibition

Photo credits: Gediminas Gražys, Antanas Lukšėnas

find out more

Room I

The very topography of the gallery, as well as the content of the collection it holds, invites to start a visit by taking a look at Vilnius through the eyes of the artists. Two albums have been already put out featuring the Vilnius theme in the Tartle collection. In the autumn of 2017, the views of Vilnius in the collection were presented to the public by the National Gallery of Art exhibition Topophilia. The current display is not big and includes works selected on the basis of their artistic level; typology – and uniqueness of the image. For example, we see such a unique motif in the painting by Marija Cvirkiene showing a circus tent. It used to be erected on the site of the Opera House and remains a vivid memory of Vilniusites born before 1960.

Marija Cvirkienė (1912–2004)

Circus, 1963, oil on canvas, 59 × 69

The paintings by Vincas Kisarauskas and Algirdas Petrulis were inspired by the horizontals of the roofs of the Old Town. These beautiful paintings of Vilnius show the town that still surrounds us. A glassed case by the entrance holds the Legend by Gediminas Karalius, one of the sketches of a monument dedicated to the founding of Vilnius inspired by the mythical Grand Duke Gediminas’ dream.

Vincas Kisarauskas (1934–1988)

Vilnius, 1965, oil on canvas, 70 × 70

Algirdas Petrulis (1915–2010)

The Neris riverside, 1967, oil on carboard, 50 × 70

Gediminas Karalius (g. 1942)

Legend, 1985, bronze, 21 × 28

Room II

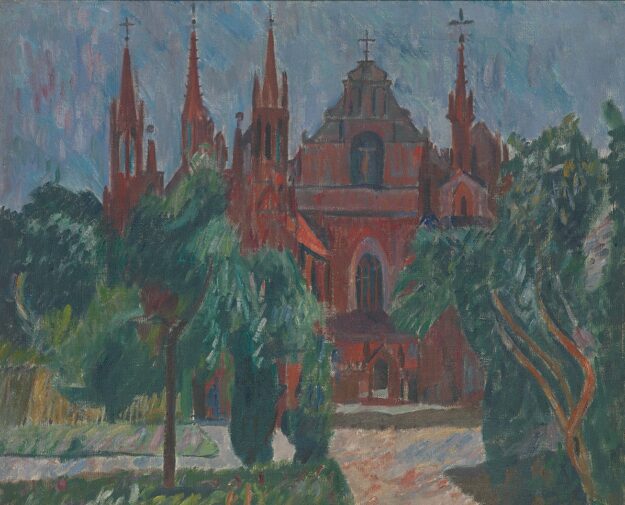

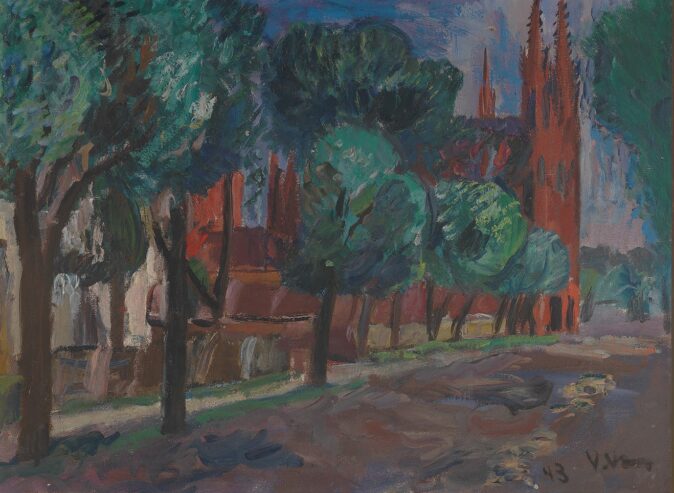

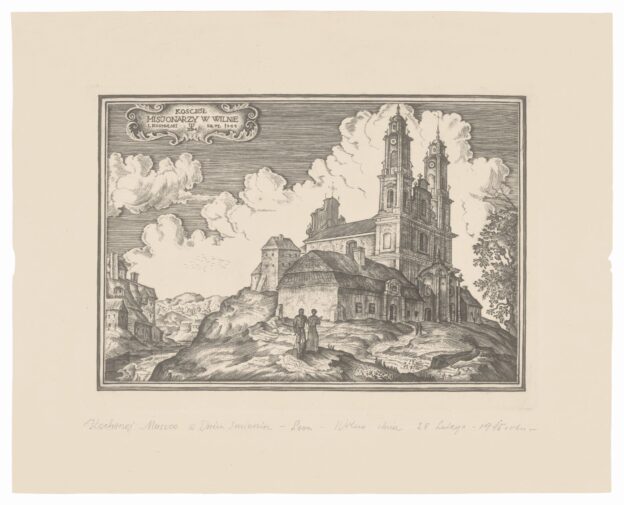

Nearly the entire room is dedicated to Viktoras Vizgirda’s artwork. It shows three wartime views of Vilnius by the artist. At the time, he worked for the Vilnius Art Academy and lived in the school’s premises with a view of the churches of St Anne and the Missionaries. The windows of the top storeys of the building also opened on the view of the former monastery and its grounds, but the panorama has already changed. Gone are not only the wooden fence, a part of the garden is now occupied by modern residential housing.

View of the exposition

Viktoras Vizgirda (1904–1993)

The Bernardine ensemble, 1943, oil on canvas, 81 × 100

Viktoras Vizgirda (1904–1993)

Šv. Onos Street in Vilnius, 1943, oil on canvas, 48 × 65

Viktoras Vizgirda (1904–1993)

The Missionaries’ Church in Vilnius, 1943, oil on canvas, 66 × 81

Unknown artist

St Christopher, 19th century, bronze, marble, 39,5 × 17

Room III

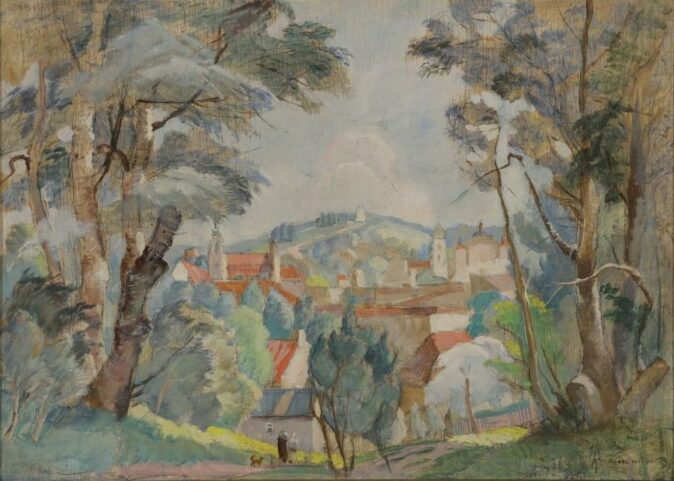

This room on the ground floor shows landscapes of Vilnius during different seasons and the time of the day. The sunny panoramas by Michał Rouba and Vytautas Mackevičius reveal the serene and joyful face of the city. Especially pleasing is Vilnius in Rouba’s Vilnius: a view from Pohulanka (1934). A view of Didžioji Street painted by Mackevičius during the years of the Second World War is quite unexpected. During those years, the artists used to paint Didžioji through the windows of the Town Hall, the then art museum, but Mackevičius found a good vantage point from the house situated behind the Town Hall, later replaced by the CAC. His perspective included even a corner of the Town Hall.

Rouba’s panorama of Vilnius, just like a panorama of historical Vilnius by Leon Kosmulski, is a utopia existing only in our imagination.

View of the exposition

Michał Rouba (1893–1941)

Vilnius: a view from Pohulianka, 1934, oil on plywood, 36 ×50

Vytautas Mackevičius (1911–1991)

Old Vilnius, 1942, oil on carboard, 34,5 × 45

Vytautas Mackevičius (1911–1991)

Vilnius. Didžioji Street, 1942, canvas and oil on carboard, 55 × 69

Leon Kosmulski (1904–1952)

The Missionaries’ Church in Vilnius, 1944, etching on paper, 22,5 × 28

Leonas Kosmulskis (1904–1952)

Vilnius, 1938, copper engraving on paper, 24,5 × 36

Reality presses hard when looking at the surprisingly alike views of the Old Town in the paintings by Tymon Niesiołowski and Algirdas Petrulis. Both are of an elongated vertical shape and show a street flanked by houses with a piece of sky opening in the background, inviting us to set on a journey in time. Pilies Street by Niesiołowski changed but little since 1936, while the depicted by Petrulis Vokiečių Street is gone. The answer why these changes had to happen is a painful one, especially since the cityscapes in both paintings look equally rock-hard as they withstood many centuries of the passage of time. Such is Vilnius, ancient, multi-layered, charming, and fragile at the same time.

Tymon Niesiołowski (1882–1965)

Vilnius. Winter morning, 1936, oil on canvas, 60,3 × 50,5

Algirdas Petrulis (1915–2010)

Vokiečių Street in Vilnius, 1944, oil on canvas, 62,5 × 42,5

Room IV

Upon descending the stairs, we encounter a painting hanging in a protected area, Esther before Ahasuerus by Franciszek Smuglewicz, one of the biggest treasures of the collection and among the best late 18th – century Lithuanian paintings. It illustrates a Biblical story from the Book of Esther about the powerful pagan King Ahasuerus which reigned, ‘from India even unto Ethiopia, over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces’, his unruly wife Vashti, and Esther, taken for a daughter by Mordecai, a Jew, and a wise king’s servant. The king made Esther queen instead of Vashti; while later Esther risked her life by seeing Ahasuerus uninvited to petition him to spare her nation from the persecution of Haman, king’s henchman. The story goes how Esther, upon entering the inner court of the king’s house and seeing the ruler, turned white and fainted, reclining against her chaperoning maiden. Moved by this sight, overpowered by compassion and love, ‘the king held out to Esther the golden sceptre that was in his hand’ [Esth.5[2]] signalling that he forgives the woman’s coming that was not ‘according to the law’. Smuglewicz depicts this very moment. It is true, that viewers, unaware of the Biblical story, will have hard time to see woman’s reverence and noble sacrifice, as the eye is attracted to the woman’s exposed nakedness, emphasised by a slipping, from her pale shoulders, silk cloak, trimmed in ermine. The story can be further read from the gestures of the characters.

Franciszek Smuglewicz (1745–1807)

Esther before Ahasuerus, 1778, oil on canvas, 78 × 100

In a niche by the staircase, before the fainting Esther, there hangs an image of a modern looking woman. It is a painting by the Vilnius artist Wincenty Slendziński, known as Portrait of Anna. Surprisingly, this luxurious and elegant portrait was created in exile. Wincenty Leopold Sleńdziński (1837–1909), the son of the painter Aleksander Sleńdziński, received sponsorship from Count Benedykt Tyszkiewicz to complete his studies at the School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture in Moscow. He was sentenced to 20 years in exile in Kniaginin for participating at the very beginning of his career in the 1863 uprising. He was only given permission to go abroad to continue his studies in 1872. After staying for a while in Krakow with his brother Aleksander, where he made the acquaintance of Jan Matejko, he went to stay in Józef Ignacy Kraszewski’s house in Dresden in 1873. He was exiled again in 1875, and lived in Kharkov and Sumy. By 1882, he had painted 266 pictures. He returned to Vilnius in 1883 when he was pardoned by the Tsar. He became known as a painter of religious pictures and portraits, painted several genre scenes, and restored old paintings. In 1888, he married Anna Bolcewicz (1845–1923), the widow of the famous photographer Józef Czechowicz. They had two children together: a daughter Johanna and a son Ludomir, who also became a famous artist. The portrait of his wife’s namesake Anna (or maybe she was his future wife?) that he painted in 1878 in Kharkov radiates with the joy of life, reflects the painter’s admiration for his model, and exudes no bitterness of exile, sadness or nostalgia.

Wincenty Leopold Slendziński (1837–1909)

Portrait of Anna, 1878, oil on canvas, 66 × 53

The same room where we can see Esther through the glass pane, as well as a different woman’s status in a different epoch in the Portrait of Anna by Slendziński, two landscapes are also on display. It is another case of a dialogue between different epochs and countries. The paintings by the 19th century artist Jóseph Marszewski and the 20th century painter Antanas Žmuidzinavičius show, correspondingly, Italy and Lithuania. Both images are idealized and convey the artists’ deep fascination with their motifs inviting us to look at them through the same eyes. It is amazing how Žmuidzinavičius comes to see the coast of the Baltic just as the Mediterranean, the cradle of European culture and the bottomless source of inspiration for many artists across countries and times. We must admit, that he is convincing enough, especially if the viewer has ever witnessed a summertime sunset from the dunes of the Baltic.

Marszewski, a graduate of St Petersburg Academy of Art and of Dusseldorf School, famous for its landscape painters, was obliged to travel to Italy glorified during his studies as a country of ideal beauty. Marszewski liked painting water and relished in depicting the play of light reflected on its surface. The lighting effects were his favourite professional challenge. Some of the best known of Marszewski’s landscapes are nocturnes, while his views with rivers stand out among his Lithuanian landscapes. This Italian landscape was painted most likely somewhere in the south of the country. It is there the sea is covered by a tender mist, and palm trees that look like tinted paper cuttings against the backdrop of a morning or evening sky. A small female figure, or rather, her colourful apparel, is also more typical for southern Italy. The appeal of Marszewski’s landscape is in these typical features. It is the Italy longed by many a romantic soul nostalgic for the past.

A View from Birutė Hill by Žmuidzinavičius illustrates how Lithuania lends itself to views of exquisite beauty just like Italy. The artist continues to be loved and valued for capturing unique moments of morning or noon tranquillity over the lakes of Dzūkija or coastal pine trees painted purple by the setting sun, the images which are most precious to the eye of Lithuanians. We can image the gratitude his contemporaries must have felt to the artist. His sunset over the Baltic was painted in the midst of the horrors of the Second World War when the whole world seemed to on the brink of collapse.

Józef Marszewski (1827–1883)

Italian landscape,1866, oil on canvas, 24,5 × 36,5

Antanas Žmuidzinavičius (1876–1966)

View from Birutės Mountain in Palanga, 1942, oil on canvas, 42 × 51

Room V

In this room, the ‘Gold Fund’ pieces in the collection map out the development of 20th-century Lithuanian art from Symbolism through Abstract Expressionism. At the same time, the works evoke two extreme states of mind – contemplation and logic, and passion. Such an approach reveals the entire spectrum of the Tartle collection, the variety of exhibits and complexity of semantic network connecting them, woven in the course of migration of people, ideas and fashions. On display is art produced by a multinational community of artists, in Lithuania and outside it; of different fates though, they were linked as teachers and pupils, followers and emulators. Their art partook of mainstream world values and at the same time was nourished by the local scene. The artwork speaks to everyone, but especially powerfully to us, as it became integrated as part of our identity. Identity always marries a genius loci with a specific civilization, the achievements of which feed into self-awareness of humans living in a given historical time period.

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

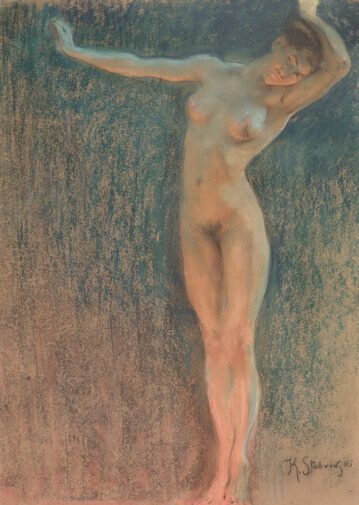

The room offers a look at the beginnings of the national art. Two perfect examples of Symbolism – Rivulet in winter (1911) by Petras Kalpokas and the Dawn by Kazimierz Stabrowski (1902), the teacher of M.K. Čiurlionis. Both paintings reflect high hopes for everything: dreams about a happy life of two people (the Dawn portrays Stabrowski’s young wife sculptress Julia Janiszewska and the picture in pastels was painted the year Stabrowski and Janiszewska were married) and the awakening of the nation and the state symbolized by the image of nature breaking free from the fetters of winter. Besides sharing happy expectations, both pieces show interest in light and the depiction of it. The interest and value of Stabrowski’s painting is increased by its frame, which is a telling example of period’s style. This element reminds us of what we read in art dictionaries about Symbolism art using means of expression borrowed from Realism, Art Nouveau and abstraction. The impressions of Rome by Stabrowski demonstrate that no national art can grow entirely from itself, but needs impulses from outside and contacts with larger cultures. In the same context emerges also the role of water for symbolical images and for the study of light and its reflections as important objectives pursued by early 20th-century artists.

Petras Kalpokas (1880–1945)

Rivulet in winter, 1911, oil on canvas, 43 × 55,5

Kazimieras Stabrauskas (1869–1929)

Dawn, 1902, pastel on paper, 63 × 44,5

Kazimieras Stabrauskas (1869–1929)

Emerald pond at the Villa d’Este, ca 1925, pastel on paper and plywood, 49,5 × 68

The exhibition offers two urban landscapes painted at an approximately the same time, Kaunas by Vladas Eidukevičius and Paris by Mstislav Dobuzhinsky. Dobuzhinsky was a Russian painter with his roots in Lithuania, who always cherished sentiments and was attached to Lithuania, lived and worked in Lithuania for considerable time. He was visible and known on the world’s art scene and saw quite a bit of the world himself, thus his art was never limited by local themes. His artwork and pedagogical involvement, as well as his texts, expanded the cultural field of interwar Lithuania. The painting shows land works by the Seine River, probably the deepening of the riverbed, or loading sand into barges, or even constructing the underground. The picture shows construction site with a dragline excavator.

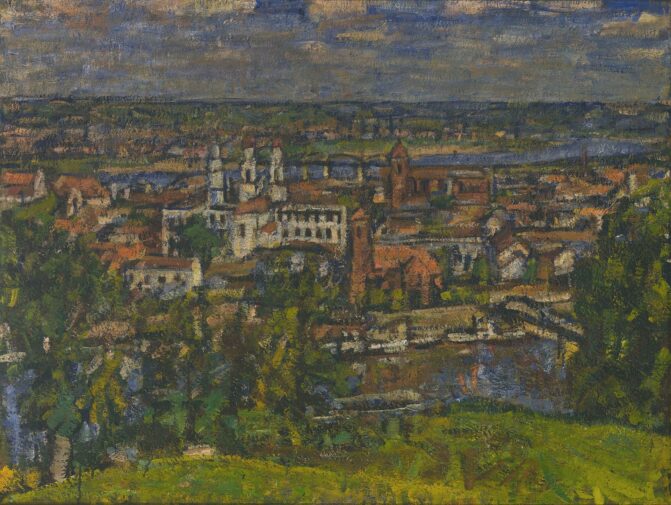

Born in Riga, Vladas Eidukevičius travelled all over Europe, and was willing to see Kaunas like a big European town too. He was one of the few artists who painted urban panoramas of Kaunas during interwar period. He liked to look on the town from above. In this painting, he looks at Kaunas from Aleksotas Hill where the artist lived, while the permanent exhibition of the National Art Gallery includes his view of Kaunas from Žaliakalnis.

Vladas Eidukevičius (1891–1941)

Kaunas from the Aleksotas hill, 1930, oil on canvas, 79 × 100

Room VI

Contemplation is the state of mind when the artist takes time to absorb natural, human and formal beauty and uses artistic means of expression that help him to convey that experience to the viewer. Contemplation requires silence and concentration on artist and perceiver’s part and brings them peace. It is a process that gives our body rest, but stimulates intense intellectual and emotional work without which not a single idea can be born in art, science, business or politics. Contemplation is also the state of mind of a collector during these rare moments when he admires his collection, its rarities and the biggest treasures, such as these pieces selected for this exhibition. Probably, the most frequent subject of contemplation is nature. That is why landscapes and flowers dominate in Room VI. There are also some figure paintings, reminiscent of the so-called Arcadia scenes – utopian peaceful gatherings or coexistences in bucolic settings transported to ancient times.

Room VI features an early still life by Tymon Niesiołowski, a Polish painter connected with Vilnius Stephen Báthory School; a painting by Rimtas Kalpokas from the 1930s; a superb sketch by Antanas Gudaitis from the 1940s, and a landscape of the 1960s by Vincas Kisarauskas. Ksenija Jaroševaitė, Antanas Martinaitis, Audronė Petrašiūnaitė, Algirdas Petrulis and Leonas Strioga are the artists representing the 1980s. Niesiołowski, Petrašiūnaitė and Petrulis were admirers and in a sense followers of Pierre Bonnard, the great master of serene, homely, and beautiful mundane scenes. Such images by him and his adherents showing enclosed living spaces, home interiors or garden scenes came to be known by the term of Intimism.

View of the exposition

Prayer requires exceptional concentration of thought and feeling, such as embodied in a sculpture piece by Ksenija Jaroševaitė. The room dedicated to contemplation invites us to think also about the paths along which the story of Lithuanian art evolved.

Ksenija Jaroševaitė (g. 1953)

Psalm I, 1988, bronze, 47,5 × 27

Rimtas Kalpokas Landscape of an Italian village (1934) was on display for public in Lithuania probably only during pre-war years, included into the First Autumn Exhibition by the Lithuanian Artists’ Association in 1935. Reviewing the exhibition, a pinching art critic Estera Elijaševaitė-Veisbartienė noted that Kalpokas’ Italian landscapes ‘show modernist defiance of Italian vibrant colours’. It is obvious that she was guided by a stereotype and had not seen Italian countryside colours stilled in sultry air. It is likely that she had not seen landscapes by Giorgio Morandi and his subtle renditions of these subdued colour schemes. Rimtas Kalpokas lived in Italy with his father, came to spend several years in Lithuania and returned to Italy to study. Italian countryside for him was an exotic artistic subject as he knew first hand only the life in towns. This painting shows the Italian countryside as he saw it thanks to the paintings by his contemporaries. The motif and its rendition, composition, colours scheme and light are similar to his teacher Raffaele De Grada’s landscapes of the same period.

Rimtas Kalpokas (1908–1980)

Landscape of an Italian village (Pescara, d’Anunzio’s native land)

1934, oil on carboard, 50 × 60

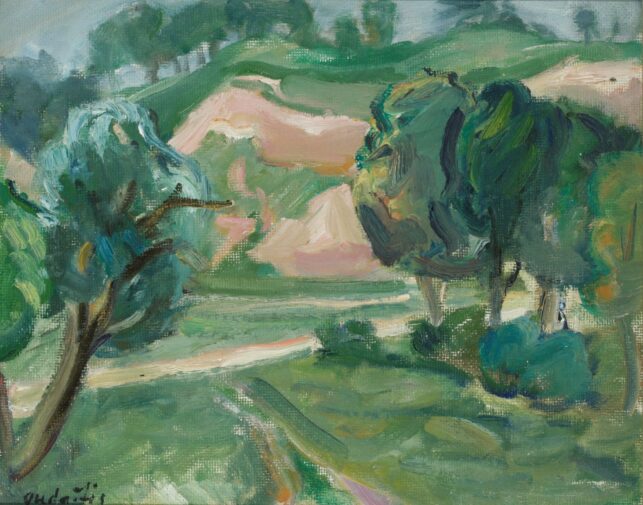

Antanas Gudaitis (1904–1989)

Landscape, 1945, oil on carboard, 32 × 41

Algirdas Petrulis was an exquisite colourist and the embodiment of harmony as an artist and a person. His very presence radiated peace and kindness, while his professional finesse enabled him to project his state of mind into his paintings that teach us to perceive beauty in small and seemingly insignificant things.

Algirdas Petrulis (1915–2010)

Lake Pakasas, 1985, oil on canvas, 73 × 92

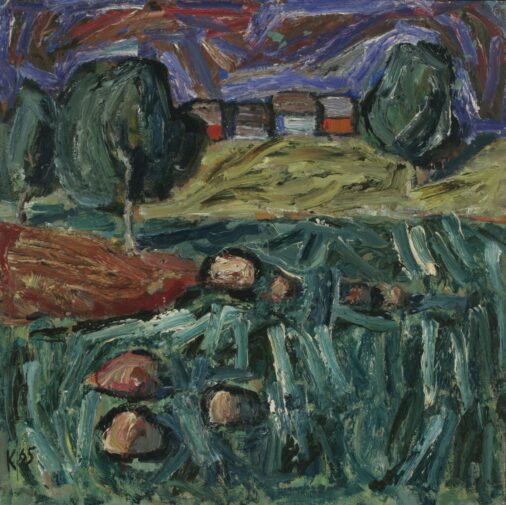

It seems that the painter expected the lovely and familiar-to-the-eye landscape of Lithuanian countryside would assuage the anxiety-torn Vincas Kisarauskas’ heart. The disquietude is unstated only, as the painting speaks about the healing effect of a rural view and a meditative painting process.

Vincas Kisarauskas (1934–1988)

Summer, 1965, oil on canvas, 70 × 70

Antanas Martinaitis (1939–1986)

Women, 1986, oil on canvas, 100 × 120

Antanas Martinaitis (1939–1986)

Madonna and child and others, 1982–1984, oil on carboard, 47 × 57

Antanas Martinaitis (1939–1986)

Madonna and child, 1981, oil on carboard, 50 × 71

Audronė Petrašiūnaitė (g. 1954)

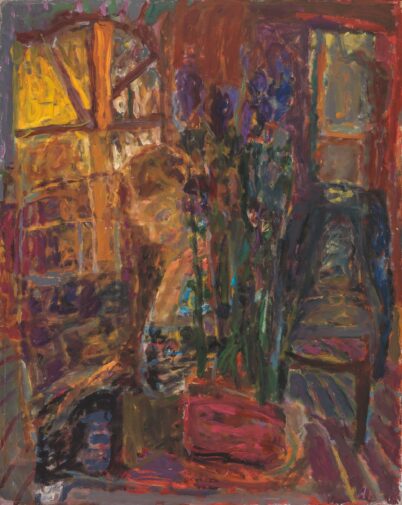

Yellow light, 1984, oil on canvas, 112 × 90

Tymon Niesiołowski (1882–1965)

Flowers in a white jug, after 1912, on plywood, 56 × 44

Room VII

Passion is often straightforwardly linked to expressive renditions of feelings, to abrupt brushwork or sculpting movements, to colour contrasts and lightning effects. In reality, passion in the works of art finds a diversity of expressions. The artwork on display, however, illustrates the first strategy: in them we see dramatic brushwork and figure movement, vibrant, contrasting colours loaded with emotion. All the artists showcased in this room led a tumultuous life. Some were even driven from home and homeland, being unable to settle in one place, others were riding the story waves of feelings bringing them to deep abysses or, sometimes, to quiet standing waters. Pranas Domšaitis from Prussian Lithuania travelled as far as South Africa, Matas Menčinskas tried to settle in South America. Kaunas was too small for Vladas Eidukevičius, who kept travelling Europe. Antanas Samuolis, suffering from tuberculosis, poured the heat burning his body into Expressionistic canvases. His Sunflowers are a declaration of his kinship with another anxiety driven genius of Modernism, Vincent van Gogh. A powerful passion of life and art prematurely consumed the talented artist of our times Rimvydas Jankauskas–Kampas.

View of the exposition

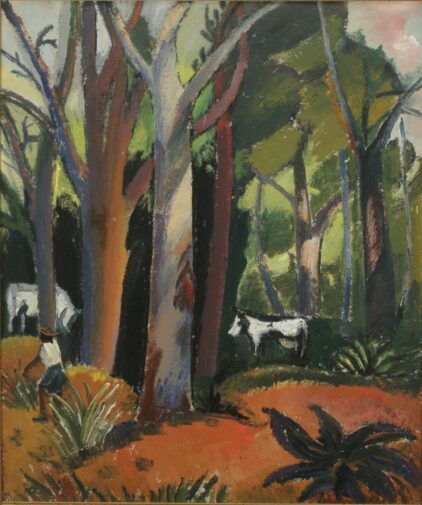

Franz Domscheit (1880–1965)

Forest in Genadendal, 1961, oil on carboard, 59 × 49,5

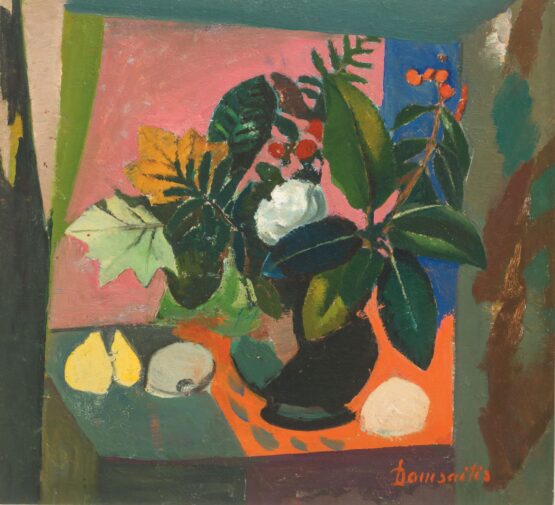

Franz Domscheit (1880–1965)

Still-life with flowers and fruit, before 1962, oil on carboard, 55 × 60

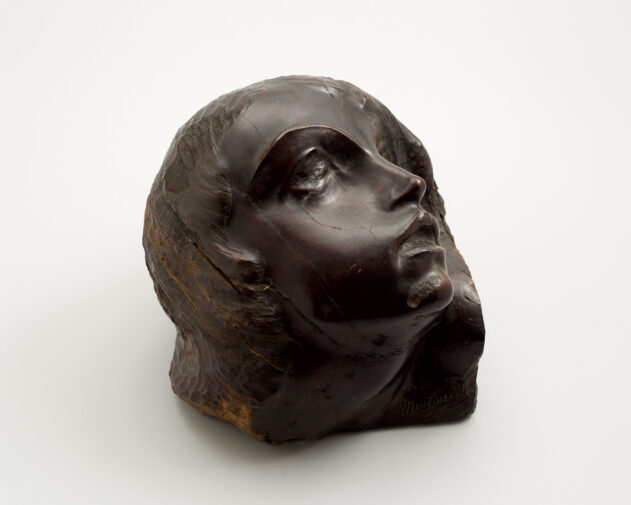

Matas Menčinskas (1897–1942)

Head of a man, 1929–1934, wood, 46 × 35

Matas Menčinskas (1897–1942)

Head of a woman, 1929–1934, wood, 29 × 39,5

Vladas Eidukevičius (1891–1941)

Flowers in a vase, 1930, oil on canvas, 50 × 60

Antanas Samuolis (1899–1942)

Saulėgrąžos, 1933, oil on canvas, 60 × 75

Rimvydas Jankauskas-Kampas (1957–1993)

Abstraction, 1990, oil on canvas, 79,5 × 100

Room VIII

This room presents a synthesis of the development of national art in the 20th century. It was the time when Lithuanian arts came of age with the return from Paris of the graduates of Kaunas Art School who had been to France to further their studies.

A great variety of tendencies emerges before our eyes: Post-Cubist rational analysis of form; Art Deco, as a version of Modernism adapted for mass user; Expressionism, enriched by experiments in colour inspired by the French Fauvists. They are manifested in the art by three figures from the Lithuanian Modernist group Ars, Antanas Gudaitis, Juozas Mikėnas and Stasys Ušinskas. All three left a deep imprint in the history of art education, not only they educated generations of art students, but shaped what in art history is called a school. The art of this triumvirate’s contemporary, Jacques Lipchitz, developed as a parallel of Post-Cubism that reached into international art scene. Mikėnas soon diverted from Cubism into Neoclassicism, from analysis to synthesis. These two elements found place in the art of his pupils as well. This dualism is most obvious in the artwork of Kaunas’ artists Mozūraitė-Klemkienė and Leonas Strioga.

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

Juozas Mikėnas got introduced into Cubism when he went to Paris, the cradle of this stylistic trend. He was perceptive enough to grasp the importance to Cubism of the art of primitives, especially created before Christianity. The legend of Lithuanian heathen culture offered an interesting match with analytical principles of Cubism. It is likely that this composition was included into the Second exhibition by the group Ars.

When Jacques Lipchitz, after studies at the conservative Crafts and Drawing School (following Ivan Trutnev’s curriculum), arrived in Paris, the melting pot of the arts, he wished for radical changes. He got highly interested in Cubism that offered new rules to transform the shapes of reality. He kept his fascination with Cubism throughout his life, becoming a member the large, in the West, Post-Cubist brotherhood and sisterhood.

Lipchitz was a contemporary of Mikėnas, both encountered Cubism in Paris. Mikėnas returned to Lithuania and relapsed into Neo-Classicism, Lipchitz stayed in the West and stuck to the rational formal analysis that occasionally led him into abstraction. Neo-Classicism with reverberations of Cubism and occasionally geometricized forms was the main method helping to shake off the tedious and debilitating canon of Socialist Realism, the dull imitation of natural forms and communist – ideology based iconography.

Notably, it was a sculpture piece The Baltic by Jadvyga Mozūraitė-Klemkienė that was selected to represent the trend of small size sculpture, significant for the 1970s, in the volume Sculpture 1975–1990 (1997).

Juozas Mikėnas (1901–1964)

Thunder, ca 1934, plaster, 75 × 26

Jacques Lipchitz (1891–1973)

The encounter, 1961 (replica of a 1913 composition), bronze, 42 × 30

View of the exposition

Jadvyga Mozūraitė-Klemkienė (1923–2009)

Baltija, 1983, teracotta, 45 × 17,9

View of the exposition

Leonas Strioga (g. 1930)

Untitled, ca 1979, wood, 120 × 64

Stasys Ušinskis was a strong influence in Lithuania, yet not only. Even those who were made to leave Lithuania received a powerful impulse from him as well. Kazys Varnelis is the most prominent example. Even connoisseurs took his artwork from the years of the Second World War for Ušinskas’. Later in his career, Varnelis was trained by Ušinskas’ school to grasp quite easily the principles of non-objective art, especially of Op Art. Such artistic mentality found way into Lithuania considerably late – at the end of the 1970s. One of Varnelis’ young spiritual brothers is Vladas Urbanavičius, separated from him by two or three generations.

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

Spring (A sketch for the plafond for Kaunas Aviator’s House), 1937, oil on canvas, 86,5 × 98

Stasys Ušinskas – dar vienas paryžietiškosios mokyklos auklėtinis, kartu su Gudaičiu patyręs apie kubizmą iš jo adeptų Fernand’o Leger ir Aleksandros Ekster; jis matė meną ir tikrovę kiek kitaip nei jo amžininkai, nes buvo užaugęs JAV; tad ir į Egiptą bei Babiloną Ušinskas sugebėjo pažvelgti per betono estetikos „akinius“; juos noriai matavosi Ušinsko mokiniai, tarp kurių buvo vėliau į Ameriką persikėlęs Kazys Varnelis. Ankstyvieji Varnelio kūriniai, likę Lietuvoje, ilgą laiką buvo laikomi Ušinsko darbais, reikėjo, kad tikrasis autorius atvyktų į Lietuvą ir atitaisytų šį apsirikimą. Varnelis tapo abstrakčiosios dailės kūrėju, kuris taikė ypatingo kruopštumo ir racionalios geometrijos žinių reikalaujantį metodą. Nieko keista, kad tapytojo Kazio Varnelio sūnus tapo architektu. Panašus mąstymas buvo artimas ir kai kuriems Lietuvos menininkams, pavyzdžiui, skulptoriui Vladui Urbanavičiui.

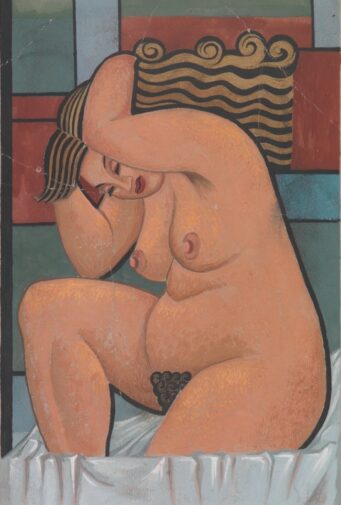

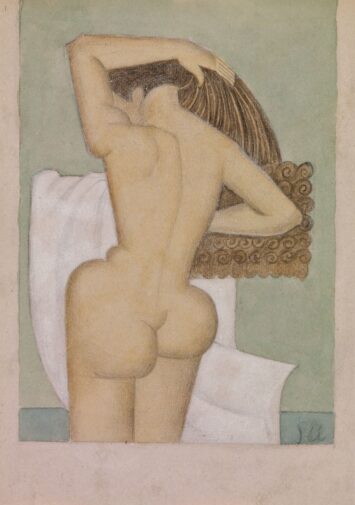

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

The mother, ca 1932, tempera on paper, 40 × 30

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

The bather, 1931, tempera on paper, 40 × 30

Stasys Ušinskas (1905–1974)

Standing female nude, ca 1931, watercolour, pencil on paper, 41 × 30

Kazys Varnelis (1917–2010)

Day, before 1943, oil on canvas, 200 × 110

Kazys Varnelis (1917–2010)

Vibrating visions #2, 1987, acrylic on canvas, 122 × 122

Vladas Urbanavičius (g. 1951)

Sculpture #2, 1987, bronze, 18,5 × 13

Vladas Urbanavičius (g. 1951)

Sculpture #4, 1987, bronze, 12,5 × 25

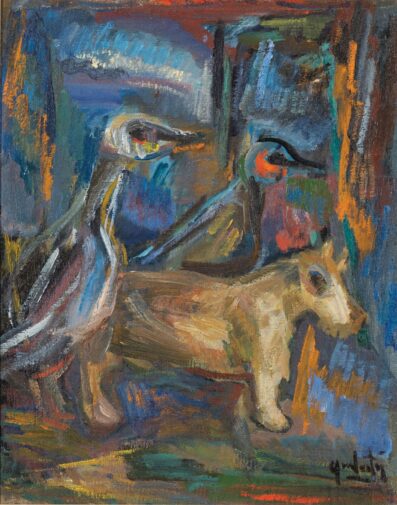

Lithuanian art in the second half of the 20th century was influenced not so much by the analytical trend as by Expressionist art of Antanas Gudaitis and Adomas Galdikas. However, it was not at the cost of logic, discipline and nearly mathematical thinking. The more so, that passion in art often tends to be translated into canons, just as it is in traditional theatre (Greek, Japanese or other). Thus, in painting such a rational expressionist was Vincas Kisarauskas who broke the limits set by Socialist Realism, in sculpture – Antanas Mončys. Based in France, he had to resist a very strong impact of 1st- half-of 20th-century Modernism and to come out of the shadow of circumstances. The force of intuition reaches its triumph in Leopoldas Surgailis’ art and can be read today as a powerful embodiment of gestural painting.

Antanas Gudaitis (1904–1989)

Mother with children, 1930, oil on canvas, 72,5 × 60

The passionate Antanas Gudaitis had to do with Post-Cubist art in Paris and tried to reach a rational balance, but was not up for that.

The motif of a white bird emerged in his art around 1966, when he painted at least two studies of a woman with a white bird on her lap. In 1979, the bird left the woman’s lap and started appearing in scenes with a bride, later on, entered his still-life paintings. Sometimes it is hard to figure out whether it is just a dream, a vision, or maybe a stuffed bird sitting next to a mask, to a wooden saint figurine by a countryside artisan, or to a vase of flowers. It is likely that this painting shows Ariel, a Scottish terrier and a beloved pet of the artist’s friend, Juozas Miltinis, the celebrated stage director of Panevėžys Drama Theatre. It is in a company of two dream birds of Gudaitis, who did his best to render as ‘lifeless’ both the real and imaginary creatures. The composition looks like a still life, a mise en scène of frozen toys or stuffed animals staged by a wilful director’s hand.

Antanas Gudaitis (1904–1989)

Still-life with a white Scottish Terrier and two birds, ca 1986, oil on canvas, apie 1986

View of the exposition

View of the exposition

Antanas Mončys (1921–1993)

Erotica, 1968, wood, 51,5 × 23

View of the exposition

Leopoldas Surgailis (1928–2016)

St George, 1970s, tempera on canvas, 151 × 161

View of the exposition